Economic growth is subject to gradation. There is almost no purpose in making such a declaration, for anyone with common sense knows intuitively that there is a difference between robust growth and just positive numbers. Yet, the biggest mistake economists and policymakers made in 2014 was to forget that differences exist between even statistics all residing on the plus side.

It was misconception sometimes by design, an almost honest error created by circumstances. The economy had been so bad for so long, six years going on seven by 2014, that it was merely assumed any upturn would be the upturn. So even when growth underwhelmed that year, those calling it “robust” and “strong” were projecting those words onto what they really believed was an intermediate stage before those terms would really apply.

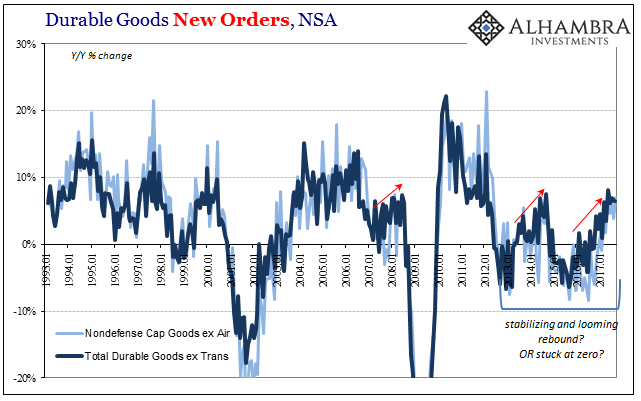

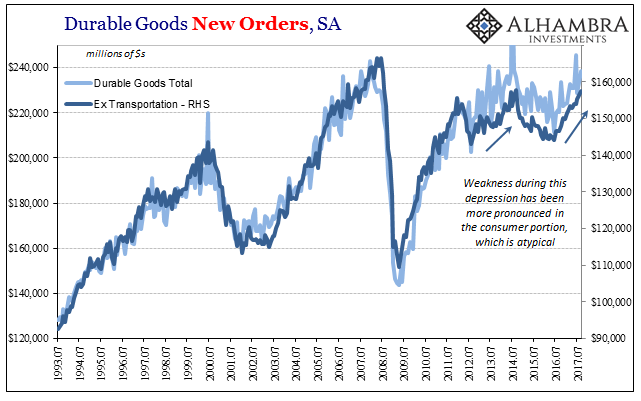

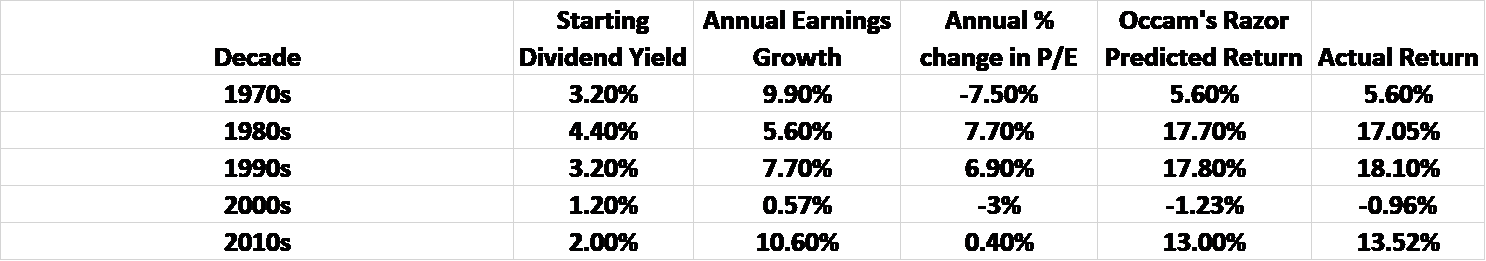

New orders for durable goods, for example, were estimated to have increased by almost double digits in a few months during the summer of 2014. According to the benchmark estimates of the time, average growth in orders was approaching 7% or better. That level of expansion isn’t actually robust, but it wasn’t ever expected that growth would stop accelerating. By the following year, 2015, given the trajectory of the unemployment rate, there was, for economists, every reason to believe 7% was just the next stop on the road to a 10% average, then 15% (as 2006) or maybe even close to 20% (as 2010).

It wasn’t ever a realistic assumption, though, merely the FOMC and Janet Yellen projecting their biases onto an economy that didn’t really exist. You could already see even by the middle of 2014 that growth had peaked, the second derivative of acceleration down to zero or close to it. There was long before then a clear lack of momentum evident just how long it took to get even to 7% (it should have happened by the end of 2013). Extrapolations are always dangerous especially when they always go in a straight line, taking no account of the slope.

There were other signs that growth was even weaker than those numbers suggested and momentum absent (the Polar Vortex being a big one). Those all suggested that the downside was considerably larger than any upside potential. It would take several years before that was fully described in the statistics. Much of that “improvement” in 2014 has been subsequently erased; it never happened.

| Economists made economic assumptions according to their standard binary model, where an economy that is expanding must actually be growing, and that any level of statistical improvement is therefore meaningful. |

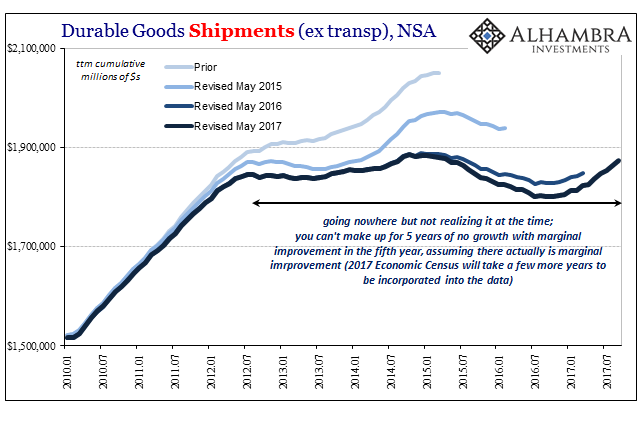

US Durable Goods Shipments, Jan 2010 - Jul 2017 |

Here we are three years later and all the same mistakes are being made.

|

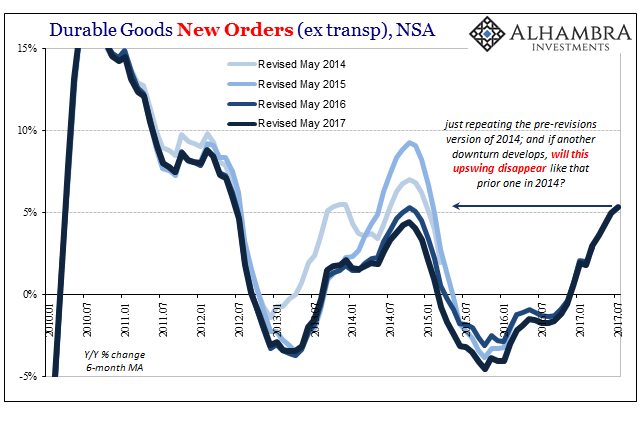

U.S. Durable Goods Orders, Jan 2010 - Jul 2017(see more posts on U.S. Durable Goods Orders, ) |

| To some extent it’s understandable if still unforgiveable. Most economists and nearly all of the media failed to account for both this difference in assumption as well as those revisions. You can’t learn from history if you don’t know your history (or for the media, ever report it accurately). |

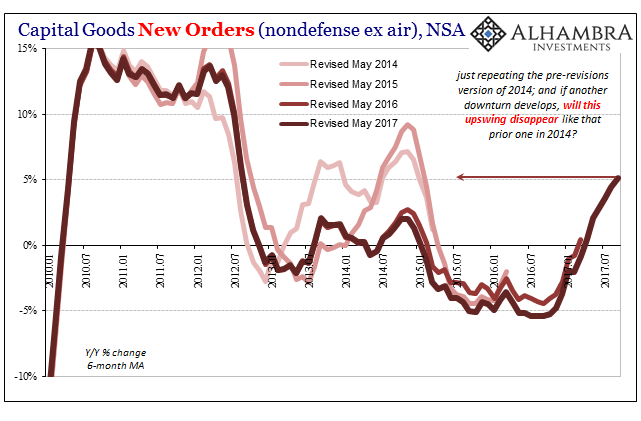

US Capital Goods, Jan 2010 - Jul 2017(see more posts on capital goods, ) |

| Durable goods orders rose in September 2017 by 6.5% over those in September 2016. That’s not robust, it’s about the same level as figured for 2014 – before the revisions. |

US Durable Goods Orders, Jan 1993 - 2017(see more posts on U.S. Durable Goods Orders, ) |

| The rest of the durables report leaves this part of the economy in those circumstances; growth but not growth, way too much 2014 and nowhere near what is really required to start using those words. |

US Durable Goods Orders, Jul 1993 - 2017(see more posts on U.S. Durable Goods Orders, ) |

Like other economic accounts, the growth rates in durable and capital goods have stayed largely at this level for about six months now. Acceleration, or momentum, is now absent for half a year (and like late 2013 there wasn’t all that much to begin with, more meandering than surging). Like three years ago, it suggests something like a “speed limit” for just how much the economy can improve under these (monetary) conditions, meaning that it isn’t really improving and there really is no basis to expect that it will suddenly start to.

The unemployment rate doesn’t matter now any more than it did then. It is, in fact, less relevant today simply because the entire economy has been acting contrary to what it suggested for several years running. There was no better test of the measure’s veracity than the serious, near-recession downturn of 2015-16 when the unemployment rate was falling the fastest (and then failed afterward to account for the clear and lingering labor market slowdown).

In short, there is again in 2017 far more downside than any possible upside potential. Economics especially in the media, however, doesn’t work that way. Positive numbers aren’t subjected here to that necessary gradation. History repeats because no one reported on it correctly the first time.

Tags: capital goods,currencies,durable goods,economy,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Markets,newslettersent,U.S. Durable Goods Orders