|

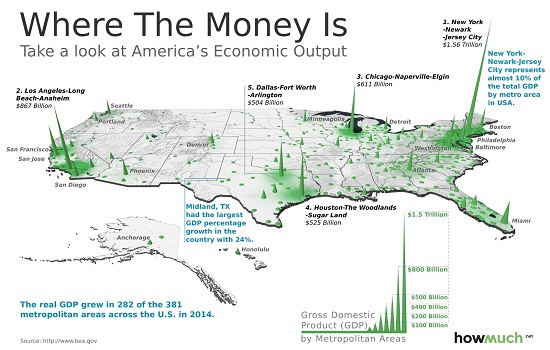

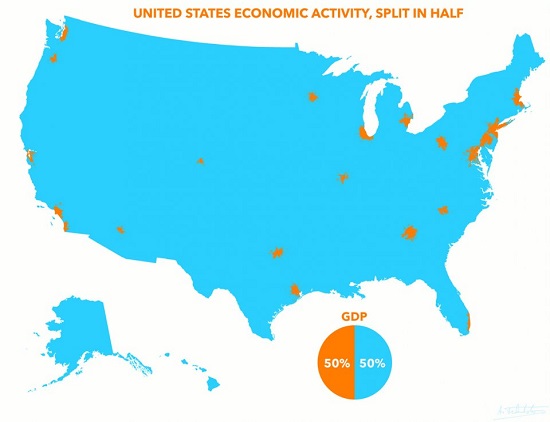

Florida’s thesis-that urban zones are the primary incubators of technological and economic growth-is well-supported by data that shows that the large urban regions (NYC, L.A., S.F. Bay Area, Seattle, Minneapolis,etc.) generate the majority of GDP and wage gains.

Cities have always attracted capital, talent and people rich and poor alike.Indeed, “city” is the root of our word “civilization.” So in this sense, Florida is simply confirming the central role cities have played for millennia.

|

|

|

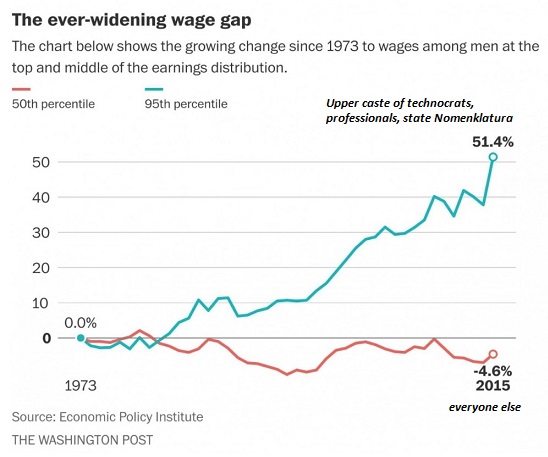

More recently, Florida has addressed the rising wealth/income inequality that is making desirable urban areas unaffordable to all but the top 10% or even 5% wage earners. This is a critical concern, because vitality is a function of diversity: a city of wealthy elites paying low wages to masses of service workers is not an economic powerhouse.

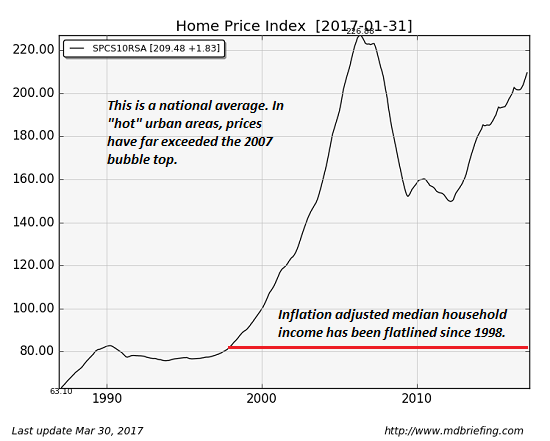

What happens as buying a home in a desirable city becomes out of reach of all but the most highly paid tranche of workers?

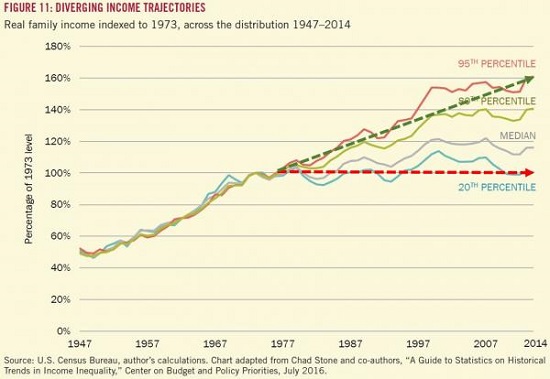

The larger question is: what happens to home ownership as housing prices continue higher while the next generation’s wages remain significantly lower than previous generations’ incomes?

Millennials are typically earning less than Baby Boomers and Gen-X did in their 20s and 30s, and if this continues–and history suggests it will–then how many Millennials will be able to buy a pricey house?

One consequence of stagnating wages and rising home valuations is a “nation of homeowners” morphs into a “nation of renters.”

The other big question is: if Millennials aren’t earning enough to buy pricey homes, who is going to buy the tens of millions of houses Baby Boomers will be selling as they downsize/move to assisted living? As for inheriting Mom and Dad’s house–that’s not likely if Mom or Dad need the cash to fund their retirement/assisted living.

This question is especially relevant to suburban homes, especially those far from employment centers. Though data on this trend is sketchy, it seems Millennials strongly favor city living over exurban/suburban living.

|

|

|

Anecdotally, I can’t think of a single individual in their 20s or 30s that I know personally who has bought a house in a distant suburb. Everyone in this age group has bought a house in an urban zone. Not a highrise condo in the city center, but a house in a ring city near public transport.

Though data on this is hard to find (if it exists at all), Millennials seem more willing to make the sacrifices necessary to live in the urban core, either by renting rather than buying a cheaper suburban home, or by purchasing a modest bungalow on a small lot rather than an expansive suburban home on a big lot.

(This could change if Millennials start having lots of children, but to date small bungalows in urban regions appear big enough for families with two children.)

In a turn-around from the postwar era, which saw a mass exodus of the middle class from city centers to suburbia, the upper middle class is moving back to urban centers and the lower-income populace–once the urban poor–are being pushed out to the suburbs. We can now speak of the suburban poor.

To some degree, the suburbs have become victims of their own success. Long commutes in heavy traffic are the inevitable result of the vast expansion of suburban subdivisions, shopping malls and business parks. These killer commutes detract from the desirability of suburbs, especially to auto-agnostics of the Millennial generation, who exhibit low enthusiasm for auto ownership.

|

|

|

Rather than symbolizing freedom, auto ownership is viewed as a burdensome necessity at best.

If we overlay these trends (assuming they continue into the future), we discern the possibility that marginal suburban housing could crash in price and morph into suburban ghettos of isolated low-income residents.

The Pareto Distribution may play a role in this transformation. Should 20% of the suburban housing stock fall into disrepair, that could trigger the collapse of valuation in the remaining 80%.

Not all suburbs are equal. Those with diverse job growth may well act as magnets much like small cities. Those with few jobs and long commutes are less desirable and have smaller tax bases to support services.

The asymmetry between modest/stagnant Millennial wages and the soaring cost of housing cannot be bridged. If these trends continue, only the top tranche of highly paid young workers will be able to afford housing in desirable areas. Given a choice between affordable ownership in a small city or in a distant suburb, Millennials may well choose the affordable small city rather than the distant exurb or low-services suburb.

|

|

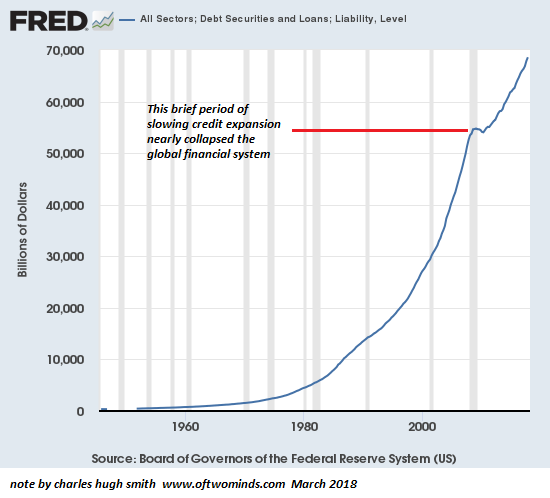

| Note that most incomes have gone nowhere since about 1998. Even the top 5% has made modest gains in real (inflation-adjusted) income.

Meanwhile, home prices are back in bubble territory. “Hot” urban areas such as Seattle, Portland, the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, Brooklyn NYC, etc. have logged double-digit gains in recent years. So who’s going to pay bubble-valuation prices for the millions of suburban homes Baby Boomers will be off-loading in the coming decade as they retire/ downsize? We know one part of the answer: it won’t be Millennials, as they don’t have the income or savings to afford homes at these prices. These trends promise to remake the financial geography of cities (large and small) and suburbia–and in the process, radically shift the financial assets of households, renters and owners alike.

|

Tags: newslettersent