Authored by Steve H. Hanke of the Johns Hopkins University. Follow him on Twitter @Steve_Hanke.

Reportage in The Wall Street Journal on April 4th states that “A fund owned by China’s foreign-exchange regulator has been taking stakes in some of the country’s biggest banks, raising speculation that it may be a new member of the so-called ‘national team’ of investors the Chinese government unleashes to support its stock market.”

Statists and interventionists around the world (read: `those who embrace State Capitalism) think “Big Players,” as the academic literature has dubbed them, will protect us from economic storms. While there is a budding and serious academic literature on Big Players – aka Market Disrupters – the financial press virtually ignores the Disrupters’ potential to bury us. Indeed, instead of stabilizing markets, the Big Players disrupt them. They are the purveyors of instability. For those who wish to grapple with the technical literature, I recommend: Roger Koppl. Big Players and the Economic Theory of Expectations. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

Big Players have three defining characteristics. Firstly, they are big — big enough to influence markets. Secondly, they are largely insensitive to the discipline of profits and losses, insulating them from competitive pressures. Thirdly, their freedom from a prescribed set of rules affords them a high degree of discretion.

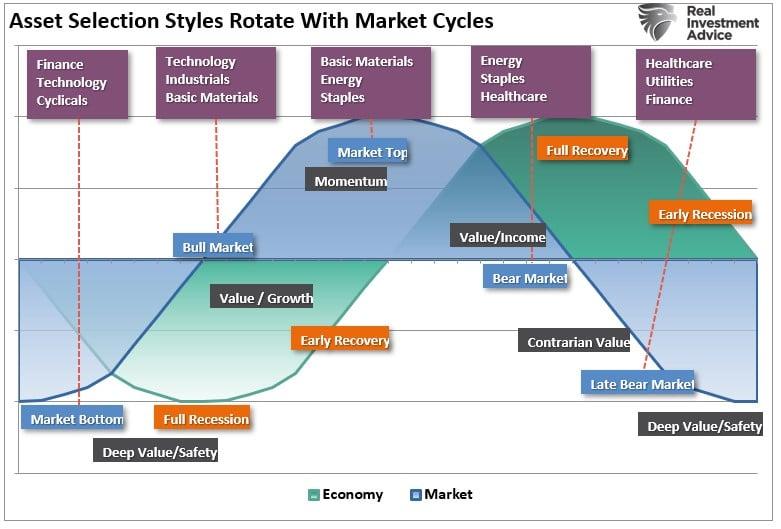

With these characteristics, Big Players are hard to predict. In consequence, they can disrupt. They divert entrepreneurial attention away from the assessment of strictly economic market fundamentals, such as the present value of prospective cash flows. Instead, the focus shifts toward attempting to predict the actions of Big Players, which are inherently political and unpredictable. This reduces the reliability of expectations, replacing skill with luck.

The Big Players’ discretionary interventions render unreliable most market signals about fundamentals. They foster environments that are ripe for herding and bandwagon effects, as well as noise trading, which is subject to fads and fashions. This partially explains why investment groups are spending big bucks to create a thinking, learning, and trading computer — a search for a master algorithm. Never mind. Big Players heighten volatility and create bubbles. They are the disrupters of the universe.

Just who are the Disrupters? Most central banks possess all the characteristics of Big Players in spades. Since the advent and implementation of quantitative easing (QE), they have become bigger players, with the state money they produce making up a much greater portion of broad money (state, plus bank money) than before 2009. Not only have their balance sheets exploded, but the composition of some of their balance sheets has changed in surprising ways. Not so long ago, central bank assets were largely comprised of domestic and foreign government bonds. Well, now you can find corporate bonds on some central bank balance sheets. And that’s not all. Central banks use their discretion to purchase equities, too. Just take a look at the Swiss National Bank (SNB), one of the alleged paragons of conservative central banking. By late last year (Q3), the total value of stocks held by the SNB had risen to $38.95 billion. That’s the size of some of the largest hedge funds in the world, and amounts to over 5 percent of Switzerland’s GDP.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) is also openly a big buyer of stocks — namely, Japanese ETFs. The BoJ is authorized to purchase roughly $25 billion of ETFs per year, and the government leans on the BoJ to use its fire power — especially when the Japanese stock markets are “weak.”

The rogues’ gallery of Big Players also includes: sovereign wealth funds, state-owned enterprises, and many other friends who do the State’s bidding.

We are becoming grossly over-reliant on Big Players. In consequence, fundamental-based investing has been forced to take a back seat and the markets have become less safe.

Tags: Bank of Japan,central banks,Japan,newsletterNotSent,Quantitative Easing,Swiss National Bank,Twitter,Volatility,Wall Street Journal