Update December 2014: SNB introduces negative rates, a toothless measure? Read here.

It is clear, therefore, that the SNB has set the exemption threshold at a level which does not penalize the banks for holding high reserve levels (reserves have been inflated as the side-effect of the SNB’s large FX intervention – partly unsterilized – of recent years), but which does aim to push the interbank rate well below zero. If the exemption threshold was set at, say, 10x minimum reserves, it would impose a high tax on bank profits, whereas an exemption threshold of 30x would fail to bite. This arrangement is reminiscent of that in Denmark, in which the negative interest rate is only applied to a limited portion of banks’ reserves. (source Fast FT).

Why negative Swiss rates would imply that the Swiss franc appreciates

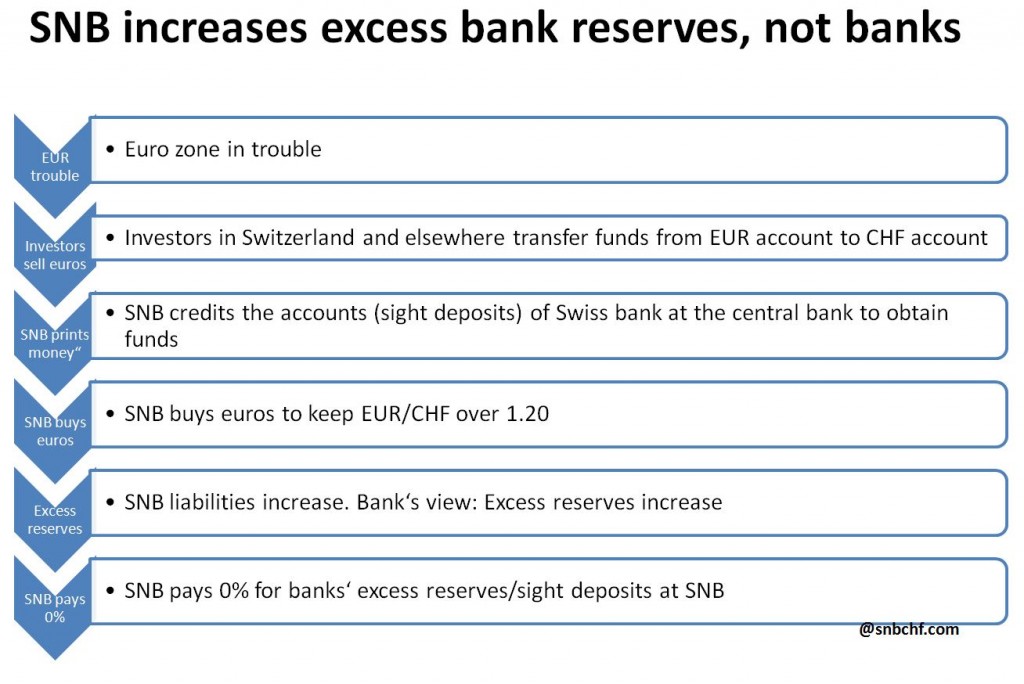

In the following we establish two points of view for rising excess reserves at the SNB:

View 1: Massive inflows in CHF lead to higher excess reserves, but intensify lending and potentially inflation.

View 2: SNB intervention leads to higher excess reserves than they would be otherwise.

View 1: Swiss banks are not hoarding cash, but they are lending as if they were no crisis

At first sight, one could say that the massive inflows in Swiss francs and Swiss bank accounts mirrors the opposite way, namely that banks hoard cash and consequently they must deposit this cash at the central bank because there is no other use. This is wrong:

First, Swiss banks are lending quite heavily, the Swiss have a real estate bubble, M3 is rising by 7.7% per year since 2009.

Rising credit is also visible in M3; monetarists and Austrian economists identify increases of total broad money with upcoming price inflation.

We explained that the Swiss real estate boom exercises a 0.25% upwards pressure to the CPI, to price inflation. Wages should increase by 0.9% in 2014.

Secondly, Swiss banks would be most happy to lend out the funds to banks in the struggling euro zone countries that have to difficulties to access private markets in exchange to some nice high-yielding bonds. Yes, Swiss banks would like to convert the francs in euros and obtain some higher interest rates. But then they run into three issues:

A) They might suffer exchange rate losses when in some years, the SNB exists the minimum euro exchange rate policy exactly due to the inflation issues above. The only remedy would be if the SNB pegged CHF to the euro forever renouncing to its right on monetary policy. In this case, deposits at Swiss banks would become a cheap risk-free financing source for Southern European banks similar as German deposits are risk-free financing inside the Target2 mechanism.

B) We question if reduced lending in the periphery is a question of austerity or of missing creditworthy borrowers.

C) While lending to a central bank has no risks associated, any lending of excess reserves to commercial banks, and even more to the ones in the European periphery increases risks and lowers risk-weighted assets (RWA). This is the very last thing Swiss banks can currently afford .

Still, lending to Europe would have been a lot easier if the currency risk were smaller. With an exchange rate of EUR/CHF or 1.10 or 1.00, Swiss banks might have increased lending to peripheral banks, because they would get the euro far cheaper. Inflationary risks in Switzerland would show up later when the SNB had allowed a stronger CHF. The euro of 1.20 is simply too expensive for them.

View 2: SNB intervention provokes increases of excess reserves

Given that the SNB intervened we come back again to the common picture seen above:

Each time there are inflows in Swiss franc, the SNB intervenes, it asks commercial banks to provide CHF funds and it increases its liabilities with these banks, those are called “sight deposits” for the central bank. From the commercial banks’ view this means that excess reserves go up.

These banks are able “to lend” funds to the “poor” central bank only because previously some rich investors came and decided to hold francs at a Swiss bank and/or moved funds from their euro account to a Swiss francs account. The banks are loyal to the central bank and are ready to lend for 0%.

But they are loyal to the SNB only because there is no other bank that offers more than 0% for reserves in CHF; Swiss banks are not reserve-constraint; the only constraint for lending is the profitability for each borrower compared to the risk associated: the 7.7% increase in M3 per year shows that they see not so many risks.

In the following we show that if the SNB introduces negative rates then the Swiss franc might rise and the EUR/CHF floor would be endangered.

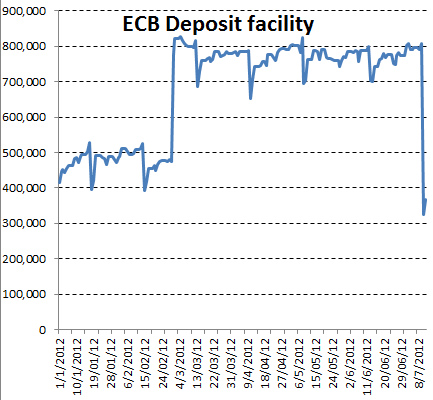

Negative Rates on ECB deposit facility

Since August 2012, the ECB does not pay interest on banks’ deposit facility, the ECB finally introduced negative rates on the deposit facility.

Based on the International Monetary Fund’s annual report on Switzerland, FT Alphaville emphasized:

The conjuncture of Switzerland may render some of the potential drawbacks [of negative interest rate] less relevant than in other countries. Activity in the interbank market is already very low, as all banks have excess liquidity. Switzerland is experiencing strong credit growth, particularly in the mortgage market. The impact of negative interest rates on mortgage rates depends on the pass-through. If banks cannot pass through negative rates to depositors, then negative interest rates on bank reserves would induce banks to increase mortgage interest rates; this would help curbing the growth of mortgage lending and housing prices. In this case, negative interest rates could help address the dilemma the SNB faces : low interest rates are necessary to defend the floor while fueling the bubble in the housing and mortgage markets. It would also alleviate the central bank’s pressure from expanding further its balance sheet. On the other hand, corporate loans may also become more expensive, possibly reducing already weak investment. If banks can pass through negative rates to depositors, then lending rates would decline and pressures in the mortgage markets may intensify, but the pressures may be tempered if negative interest rates reduce capital inflows. (source FT Alphaville and IMF)

The Base Money Confusion: Banks are Not Hoarding Cash

via Izabella Kaminska and Peter Stella in FT Alphaville “The base money confusion”

FT Alphaville had an interesting email exchange with Peter Stella this past week, snippets of which we would like to share (with Stella’s permission).

Stella is currently the director of Stellar Consulting, an organisation that provides macroeconomic policy advice and research to central banks, governments, and private clients. He was formerly the head of the Central Banking and Monetary and Foreign Exchange Operations Divisions at the International Monetary Fund.

He got in touch with [FT Alphaville] because of what he feels is a gross misunderstanding in policy and journalistic circles regarding the nature of central bank reserves, and the myth that banks are not lending because they prefer not to.

“From journalists, former colleagues, professors at Harvard, Yale and Columbia. I have been reading similar ideas/commentary for almost 5 years. That is, somehow bank reserves at the central bank ought to be “lent out”, i.e. should exit the “vault” of the BOE, Fed or ECB and begin circulating in the economy. The obverse of this is that an increase in excess reserves at the central bank reflects commercial banks “hoarding” liquidity rather than lending it “out”.”

All this, he feels, is leading to ill-advised policy suggestions, such as negative rates, which are wrongly believed to encourage lending. The long and the short of a closed monetary system like ours is that base money quantity is always determined by the central bank and nobody else. ….

“My frustration lies in my inability to explain to “sophisticated” people why in a modern monetary system–fiat money, floating exchange rate world–there is absolutely no correlation between bank reserves and lending. And, more fundamentally, that banks do not lend “reserves”. ”

Commercial bank reserves have risen because central banks have injected them into a closed system from which they cannot exit. Whether commercial banks let the reserves they have acquired through QE sit “idle” or lend them out in the interbank market 10,000 times in one day among themselves, the aggregate reserves at the central bank at the end of that day will be the same.”

Thus, just because deposits are rising at the ECB (and elsewhere), does not mean banks are not lending — something Bank of America Merrill Lynch has attempted to explain before too.

…..

But the point stands. [Commercial bank] reserves [at the central bank], also known as base money, can only be extinguished by the central bank as part of strategic balance sheet reduction policy. This in itself can only be achieved through outright asset sales, reverse repos, negative rates or to a lesser extent by auctioning term deposits.

Similarly Bank of America Merrill Lynch analysts:

Bank of America Merrill Lynch analysts have taken objection to everyone interpreting high use of the ECB’s overnight deposit facility as an indicator of ‘bank hoarding’.

It is just not so, they say.

In normal times, for example, there are three main areas where banks can direct their borrowed cash:

1 – the commercial banking system.

2 – turn it into physical cash.

3 – transfer it to governments via auctions.

In more technical terms, liquidity provided by the ECB takes the form of either estimated minimum reserve requirements or net autonomous factors. To unpack what those two terms mean:

Minimum reserves are the ratio of cash banks are required to maintain at the ECB in order to cover their liabilities in the commercial banking system. If they happen to have more borrowed cash on their balance sheet than minimum requirements (let’s say because they are not lending it) the excess usually ends up deposited in the deposit facility so as to earn some interest. Remember, this is borrowed cash, and banks will want to offset the interest they themselves pay to have access to that liquidity.

….

Assuming the liquidity stays within the commercial banking system, the additional cash will only disappear from the deposit facility if banks’ reserve requirements increase. (source FT Alphaville)

The Harvard Review further explains:

In the US and Japan, for example, there has historically been zero return on those reserves. So banks will try to lend out excess reserves to other banks that may be deficient in reserves. The competition in this market, called the interbank market, starts to drive interest rates down, because the banks will take any return instead of zero. If the central bank allows that process to continue, it loses control of monetary policy.

The Negative Rates Phenomenon

FT Alphaville continued:

Negative rates phenomenon

If imposed, negative rates would be enforced via the base money market. This could see banks charged for holding excess reserves at the central bank. Which ever way you look at it, the move would ultimately be contractionary rather than expansionary because it would lead to base money destruction, or wider credit destruction as banks hand over credit to cover charges. The excess reserves the central bank created with one hand would be wiped out with the other — creating an overall tightening effect unless new base money was continuously created to compensate for the contraction.

Alternatively, interest on central bank deposit facilities or reserves could be dropped altogether. This would encourage reserves to seek out principal protected assets until market rates were influenced into negative territory due to the crowding out effect, a la Switzerland

Of course, rather than hold money in negative yielding assets or in reserves that are subject to charges, banks would eventually become encouraged to hold reserves in physical banknote form instead.

….. In banking today deposits at the central bank are totally unnecessary for lending.

The consequence of Swiss negative interest rates

Translated in terms of the Swiss franc this implies that in the case of negative interest rates the banks will look for less costly possibilities to deposit their cash securely and they will avoid the SNB. This could imply that they hold cash in the form of bank notes, they could prefer to keep excess cash on their books or use the money market and lend to another bank that may even offer some very small interest percentage, but far better than paying 0.1% or similar.

Pictet adds:

.. with negative rates, there are some risks of a flight to cash. This is particularly true for Switzerland where high denomination banknotes exist. Demand for 1,000-franc banknotes has already increased quite significantly over the past few years. The introduction of negative interest rates on bank sight deposits at the SNB is far from excluded, but we believe the SNB would prefer to avoid it. It is worth remembering that in H1 2012 when the ECB was cutting rates and the SNB had to massively purchase foreign currencies to protect the floor, Swiss monetary authorities refrained from pushing official rates below zero. (source)

When, however, the base money aka excess reserves are removed, the central bank will be forced to sell assets, i.e. sell foreign currency to “balance the balance sheet”. Consequently the franc will appreciate.

This makes clear that the negative Danish central bank rates at 0.20% are only a minimum incentive and is only valid to excess reserves over a certain threshold.

Similarly the Swiss could not go for higher fees than 0.20%, or due to the higher liquidity and demand of Swiss francs to 0.10%. This again would make the whole IMF concept of negative rates impossible. On the contrary, instead of taking a similarly low “counter fee” from mortgage applicants, it could further fuel the Swiss real estate boom because banks expect higher rates even later.

See more for