Dark matter may more commonly be associated with physics, space exploration and Professor Brian Cox, but, according to Deutsche Bank’s FX strategist George Saravelos, there’s a good chance that it’s becoming a recognisable force in the world of foreign exchange too.

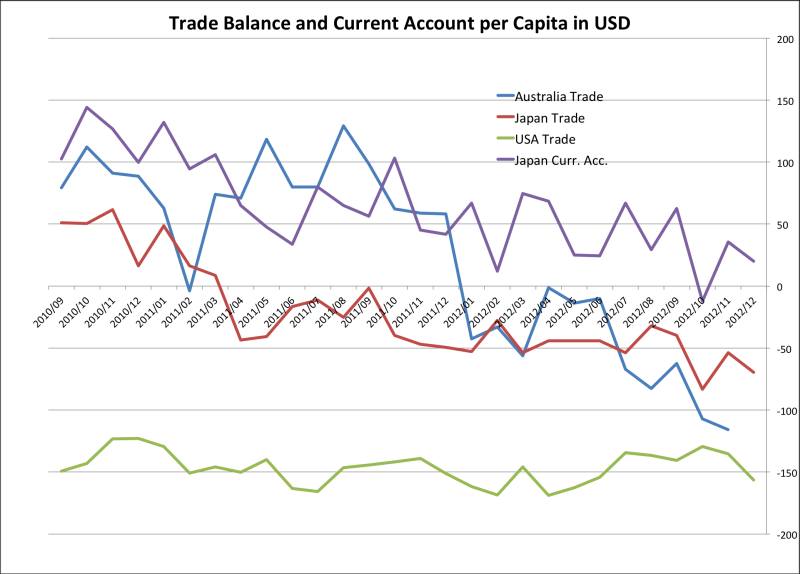

Of course, whilst you need complex structural analysis of the universe to detect the real dark stuff, in FX its presence is arguably more easily sniffed out. Mostly, says Saravelos, via the closer inspection of short-term derivative flows and the murky parts of balance of payment statistics.

From Saravelos’ Friday note (our emphasis):

FX strategists spend most of our day analysing current accounts, FDI, and portfolio flows. Yet since the Global Financial Crisis, trends in this data have been an exceptionally poor guide to currency direction. For instance, sterling has had one of the weakest basic balance of payments among global FX, yet was one of the best performing currencies last year. It appears that in our new world of tail risk, quantitative easing and abundant liquidity, unaccounted “dark matter” has been influencing currency performance beyond usual drivers.

We may now have a better answer into what this dark matter is: short-term derivative flows and outright movements of cash that do not show up in traditional balance of payments analysis.

This flow appears in an unused corner of balance of payments statistics known as the “other investment and short-term flows” category.

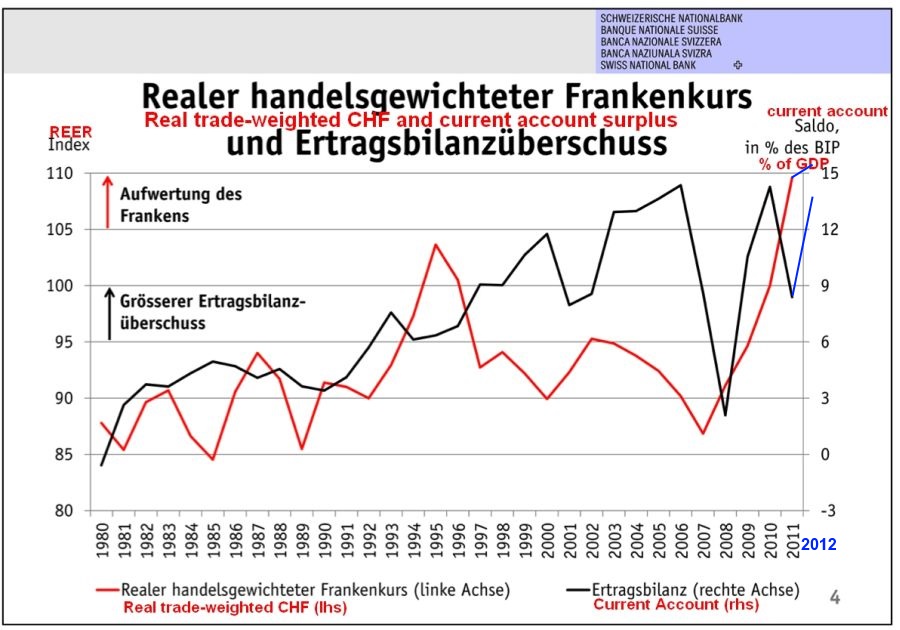

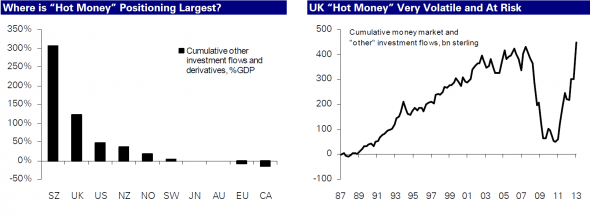

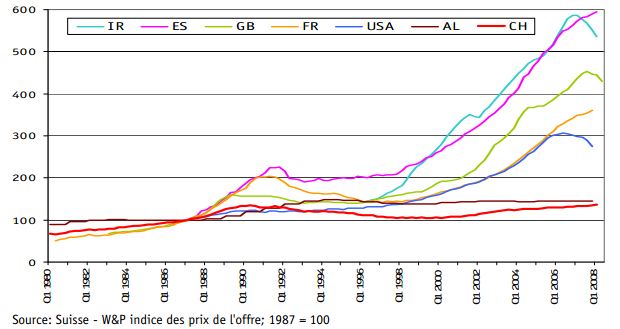

Before 2008, flows in this account were too small to matter. Since then, QE, flat yield curves and safe-haven flows have elevated this category to one of the most important flows in G10 FX. How big is it and where does it matter the most? Cumulating the inflows of “other investments” over the last few years, we can build a proxy of the outstanding stock (chart 1).

Switzerland, at more than 300% of GDP, stands out as having the largest stock. Sterling comes in second, explaining part of the pound’s recent resilience. The pound’s greatest flow strength could turn out to be its greatest weakness though.

In short, what we seem to be talking about are the ever growing effects of flighty uninsured deposits in their search for safety and any hint of positive yield.

None of which, in the opinion of Saravelos, turns out to be good news for GBP:

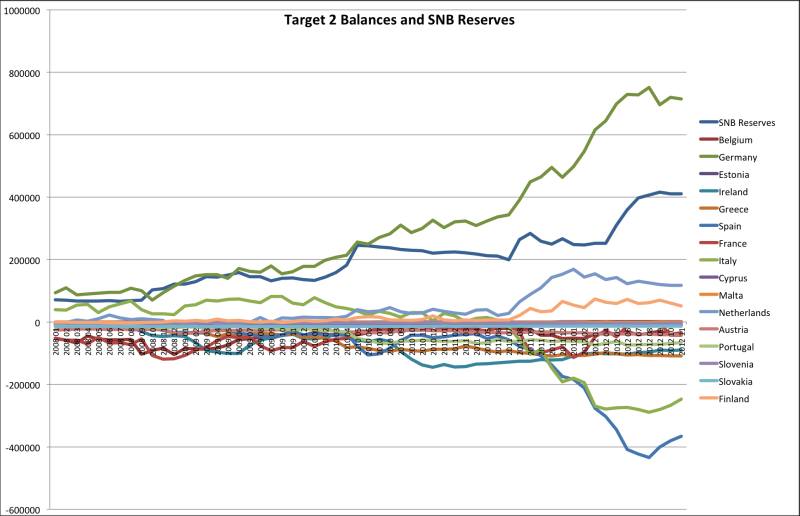

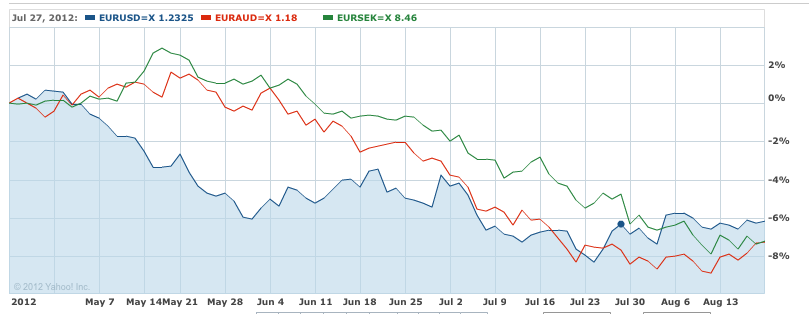

In contrast to Switzerland’s steady inflow, the UK saw a 350bn GBP collapse in short-term flows in the first few years of the crisis, only to subsequently rebound as Eurozone tail risks picked up (chart 2). This could reflect outright inflows or liquidation of UK assets and hoarding in cash. We think this pattern puts sterling at major risk this year. First, we doubt this pace of unconventional inflows can be maintained, which in turn would mean that the traditional balance of payments dynamics (trade and portfolio flow deficit) re-assert themselves. Second, we think there is a risk these inflows reverse, on the back of UK downgrade risks and ongoing exceptionally poor macro performance. Combined with the risk of a building policy premium to build into the Carney BoE leadership transition, the very poor quality of UK inflows is one of the main reasons behind our core bearish view for sterling this year: buy EUR/GBP and sell GBP/USD.

Related links:

On the flightiness of uninsured deposits – FT Alphaville

Are western central banks having an existential crisis? – FT Alphaville

Tags: balance of payments,Foreign Exchange