The recent European Parliament elections have brought the question of the role of Ireland in Europe to the forefront. Bombastic slogans adorned the leaflets of the European candidates, pledging to rightfully bring Ireland to the European orbit or to protect the country from the clutches of the mainland-based bureaucrats. Whatever the stance, it seems that the Ireland-Europe dichotomy is particularly entrenched, indubitably enhanced by our insular condition. Let us, however, try to shed some light on these identitarian questions.

The first question to ask is: “What is Europe?” We encounter the first obstacle geographically, since the geological continent is Eurasia. Traditionally and instinctively, one tends to place the limit of Europe in the Urals and the Caucasus, splitting the vast country of Russia among two continents (despite ethnic Russians dwelling as far East as the okrug of Chukotka, opposite Alaska), letting the shores define its natural borders on the North, West, and South. Linguists, including the author, would feel tempted to base the answer on Indo-European languages, which would leave us facing the conundrum of the Indo-Iranian languages in Asia plus non-Indo-European tongues on home soil such as Basque, Finnish, or Hungarian.

I once heard a creative approximation using the acronym Eu.Ro.Pa. as Euangelion-Roma-Parthenon (Gospel, Rome, and Parthenon); that is to say, the synthesis of Christianity, Roman law, and Greek philosophy. This cultural interpretation will loosely identify Europe with the concept of Christendom that reached its culmination in the Middle Ages. I believe this interpretation to be a rather accurate one if we allow some leeway for the various indigenous underlying cultures that contributed to the development of the aforementioned synthesis. This would give Catholicism a particular flavor different from Coptic Christianity, for instance, or propitiating the evolution of Common Law and our Mediæval epos (bearing in mind the caveat of fluctuating Muslim incursions in both ends of the continent). We are clearly tending towards the concept of Western civilization here, which transcended geographical barriers over the course of the past five centuries, but whose cradle lies unequivocally in the European continent.

It seems that an element of subjectivity and some compromise will be inescapable in any definition we might reach. Nevertheless, for the sake of this discussion, let us agree to find a common ground between the previous approaches and define “Europe” as the land consisting of the Western peninsula of the Eurasian continent, limited by the Urals and Caucasus and including adjacent islands, inhabited by peoples of mostly Latin, Greek, Germanic, Celtic and Slavic languages, possessing a common culture derived from Christian religion and classical Græco-Roman tradition with varying degrees of local peculiarities (notwithstanding anomalies like Basques, Muslim Bosniacs or Cyprus).

In light of that definition, the inherent European identity of an island off the mainland, of Christian religion and Celtic culture, seems incontestable. History not only confirms this, but would allow us to take it a step further. The first evidence of Ireland as part of a larger cultural continuum comes to us in the Neolithic henges, tumuli, and dolmens that align this island with the megalithic culture of the Atlantic façade, comprising the West coast of Europe from the Iberian to the Scandinavian peninsulas plus the British Isles. The subsequent Celticization of the island brought it again into the orbit of the main culture of the continent’s Iron Age, spreading from Portugal to Turkey. Posterior arrival of Christianity without direct Romanization propitiated its natural development into a very idiosyncratic culture which forms the backbone of the country. And it is this Celtic Christianity, strongly spiritual and erudite, articulated through monasticism, which results in the culmination of Ireland’s place in Europe.

In the turbulent transitioning times following the fall of the Roman Empire, the Island of Saints and Scholars kept the flame of classical culture alive. The lives of Irish saints and their evangelizing journeys across Europe; their exquisitely-crafted, illuminated manuscripts conveying wisdom from the past; the monasteries founded both on the island and the Continent which would become the main centers of learning and host students from all Christendom. All these bear testimony to the inestimable role that this island played in European history. Not without controversy, American scholar Thomas Cahill considers Ireland the true savior of Western Civilization in his book How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland’s Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe. The thesis is that, albeit somewhat hyperbolical, is founded on solid historical arguments. We can therefore conclude that, not only is Ireland an inherent part of Europe: Ireland is Europe and Europe is Ireland, existing in a contingent rather than symbiotic relationship.

Does that mean that Ireland’s rightful place is in the EU and that “Euroskeptics” are embarked in a nefarious endeavor against the country’s natural destiny?

A quick glance at our history will quickly reveal that Europe has never been politically united and any attempt to do so has always been met with natural resistance. The Roman Empire—more of a Mediterranean rather than a pan-European endeavor)—Charlemagne, Napoleon, Hitler; they all failed, or succeeded only temporarily and marginally. And such enterprises are doomed to fail because they go against the very essence of Europe—a set of political divisions, propitiated by our unique geography, yet possessing a cultural unity, expressed in a common heritage, culture, and religion.

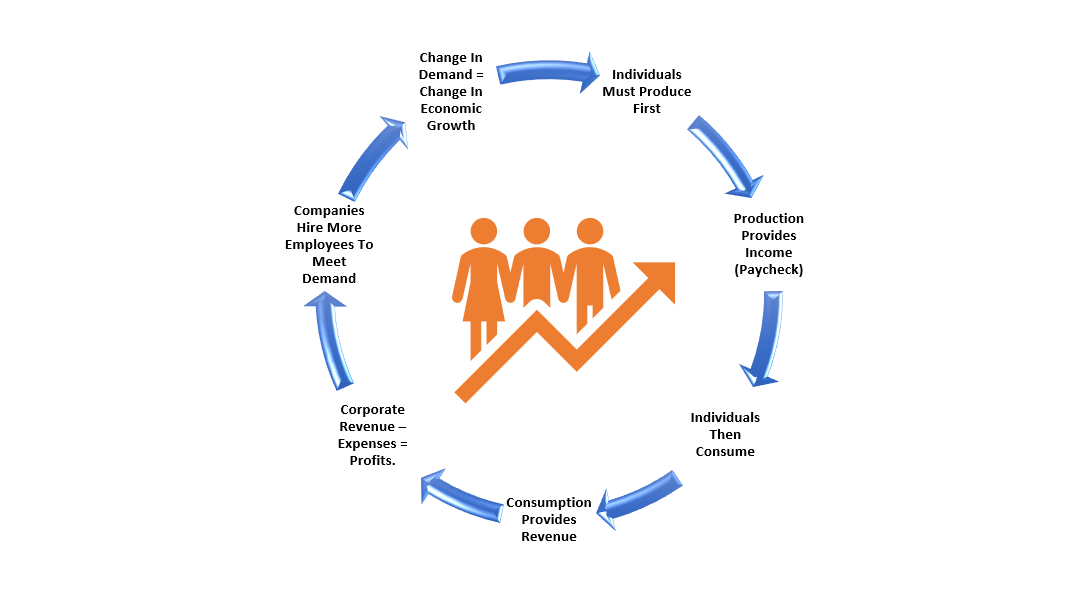

Unlike Asia, whose geographical features favor the development of agglutinative political units, such as in China or India, Europe thrives on territorial fragmentation. Renowned historians and political scientists like Eric Jones, Gary W. Cox, and Joel Mokyr consider this fragmentation not only an inherent or inevitable characteristic of our continent, but one of the reasons for its unparallel development compared to other parts of the world. For example, the so-called “Great Divergence,” amply studied in Jones’s book The European Miracle: Environments, Economies and Geopolitics in the History of Europe and Asia. The high number of small political entities in Europe fostered competition and a thriving market of ideas and technologies, whereas our common culture also favored collaboration and trade, aided by use of a lingua franca—first Latin, then French, and now, Béarla (English)—which also supported the development of a European intellectual class.

The European Economic Community, in theory, was created with the laudable aim of facilitating free trade. But the best free trade agreement is the one that does not exist. Surely, economic agents do not need any agreement to trade freely; they simply need to be left alone. The metamorphosis of the initial economic community into this current ever-growing political behemoth has been considered inevitable by many political analysts. From some mild monetary and commercial regulations, we have gradually reached a status wherein Brussels is taking over crucial decisions in matters of economy, ecology, immigration, trade, defense, and industry, often with overarching deleterious consequences. To add insult to injury, the ever-increasing political role of the EU not only threatens our freedom and economic development (which it initially vowed to protect), but its policies are also fostering a process of undermining the very common European Christian culture that made us flourish.

Political union, and dissolution of our common culture, is a complete subversion of the true spirit of Europe—political fragmentation and cultural unity. Whatever our stance on European elections, we would do well to remember that Ireland is as European as the EU is anti-European.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Featured,newsletter