In March 2013 we anticipated the upcoming weakness in Emerging Markets with our essay: The Volker Moment Redux

Here the original tweet

The “Volcker Moment” and the “Volcker Moment Redux”, also named QE2. The Successful Reduction of Global Imbalances http://t.co/GJ9Uup7s2V

— George Dorgan (@DorganG) March 11, 2013

How the Fed’s QE2 Created Overinvestment in Emerging Markets, but Reduced Global Imbalances

How the Fed’s QE2 Created Overinvestment in Emerging Markets, but Reduced Global Imbalances

We reckon that the Fed’s Quantitative Easing in 2010 (QE2) is one of the main reasons why many emerging markets started to slow considerably in the course of 2012. Due to continuous high inflation expectations in these countries, the weakness might continue for some time. As for the consequence on certain emerging markets, QE2 was quite similar to the Volcker moment in 1982 and could therefore be named “the Volcker Moment Redux”.

The German trade surplus inside the euro zone has been halved since the financial crisis, while the U.S. current account deficit has nearly been cut by two from 6% of GDP at the height of the sub-prime boom to 3.1% recently.

Let’s start with a piece of history.

The other side of the Volcker moment

The other side of the Volcker moment

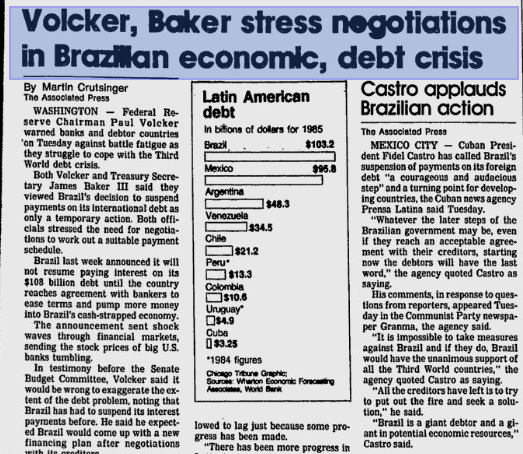

In the 1980s the “Volcker moment” was the sudden increase of interest rates that defeated U.S. inflation. Many Americans are thankful to him for that. What is less known, is that it led to a decade of low global growth, in particular in Southern America.

As a result, borrowing became expensive, in particular for Latin America. This led to currency crises: their currencies collapsed, hyperinflation started. Similar to the current austerity programs, in Spain or Greece, the IMF required that these countries reduced spending, which helped to shrink current account deficits. The combination of high borrowing costs and low spending led to a collapse in the average income in Brazil and Mexico.

Brazilian income fell by 6% between 1981 and 1994, Mexico’s growth stagnated between 1983 and 1988. With lower global consumption, oil prices fell. This had bitter consequences for oil producer countries like Mexico. Along with higher supply, an “oil glut ” appeared. A currency crisis in 1994 led to Mexico’s default. Many commodity prices, for example copper, were at all-time lows between 1981 and 1987 (see below).

Commodities remained at undervalued levels until the year 2000, while funds poured into the United States to take advantage of a technology boom with the computer age and high U.S. interest rates.

The Rise of Global Imbalances

During the financial crises of 1998, Russian and many Asian countries repeated the same mistakes as Latin America in the 1970s. In response to these mistakes, they considerably reduced their reliance on foreign capital; instead they accumulated foreign currency reserves.

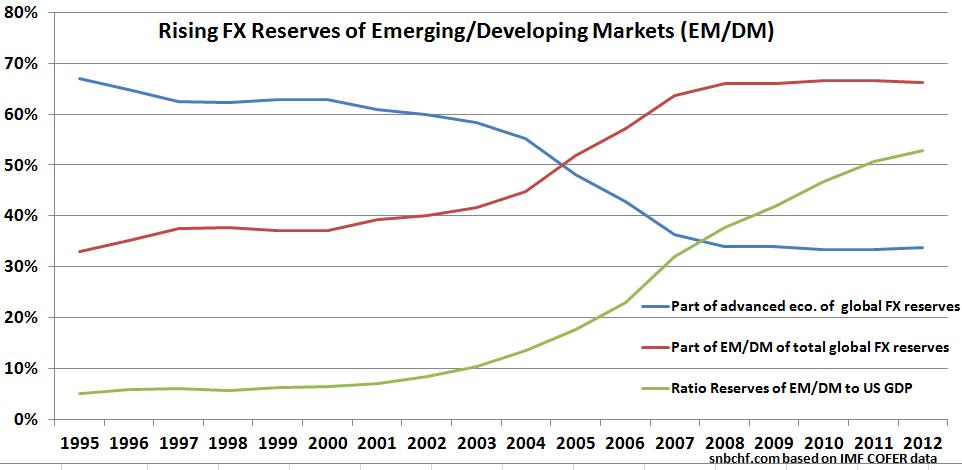

The part of global FX reserves in advanced economies fell from 68% in 1995 to 33% in 2012. Emerging Markets’ reserves rose from 5% to 53% of U.S. GDP in 2012.

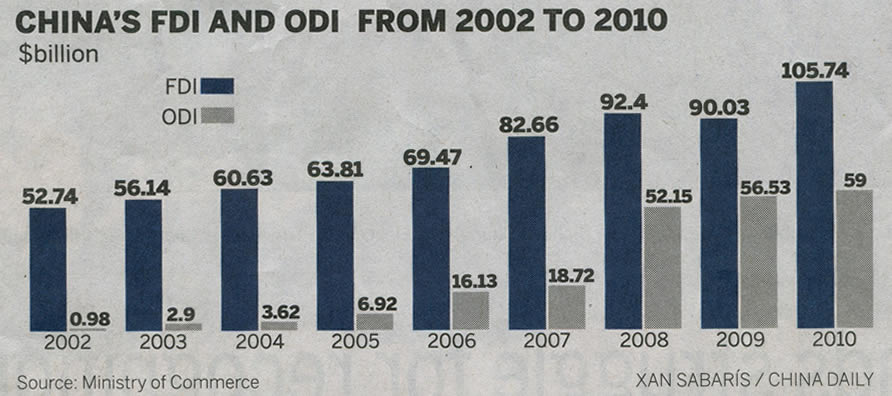

High saving rates, authority pressure on wages hampered consumer spending in China and other emerging economies despite strong inflows via foreign direct investments.

On the other hand, cheap imported manufacturing dampened inflation and sustained spending and growth in the developed world, which led to huge imbalances in terms of:

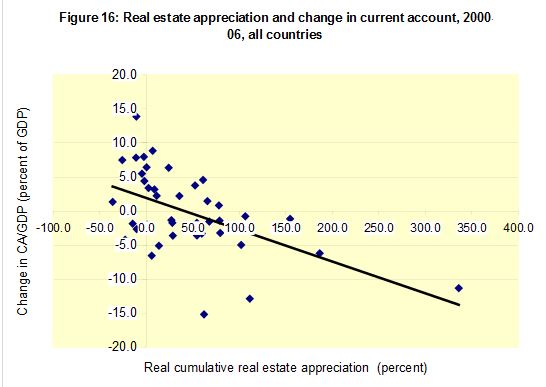

- Current account surpluses in emerging markets and deficits in developed nations, especially in the ones that were used to high inflation and higher deficits, while the Fed and other Western central banks solely focused on consumer prices (CPI) and ignored an asset price bubble. CPIs were pushed down by cheap imports and stagnating salaries due to global competition.

- There were continuing big wage differences between the developing and developed world despite easier forms of communication and outsourcing possibilities in a globalized world.

- Rising real estate prices and wages for deficit countries in the developed world (e.g. the UK, Spain or the United States) and relatively stable prices and salaries for trade surplus countries like Germany, Switzerland or Japan

But global imbalances also had an advantage: the appearance of a new “pole of growth” that is financially and as for rational expectations mostly independent from the United States, China has not more than half of the U.S. GDP. When many Americans spend less during a crisis and increase savings, this does not necessarily mean that a Chinese (or a European) does the same.

The new pole helped to dampen the effects of the 2008/2009 financial crisis. Despite the severity of the U.S. crisis symptoms, like a depressed housing market, over-consumption and low savings over many years, it did not lead to a long-lasting global recession.

On the contrary, many emerging markets like China and Brazil quickly resumed strong growth. This resulted in big growth differentials between developing nations and the U.S. Due to high oil and gas prices in expectation of high global growth, it additionally weakened the United States.

QE2: The Reduction of Global Imbalances via the Back-Door of Food and Wage Inflation

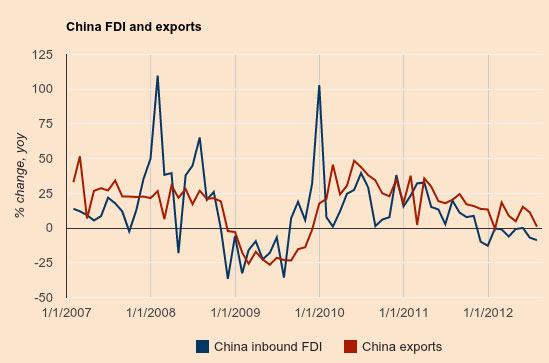

When the Federal reserve tried to weaken the US dollar and strengthen equities and U.S. investment in 2010 with big purchases of U.S. treasuries, a “currency war” was initiated. The American economy did not improve considerably, real U.S. wages were even falling. Instead, “hot” QE2 money flooded into emerging markets to profit on growth rate differentials. The hot money led to even stronger economic growth in these countries and an excessive increase of investments, especially in the housing sector that finally showed similar bubbles as occurred before the financial crisis in the U.S.

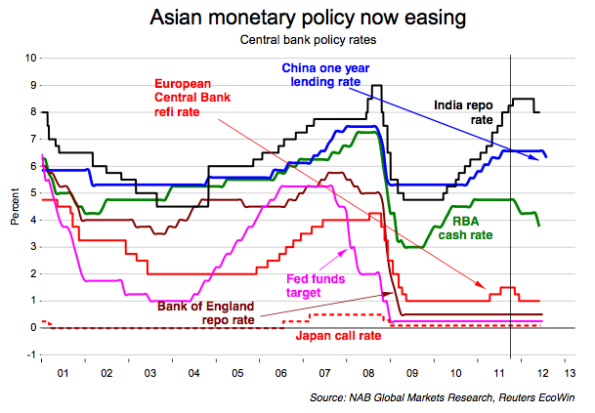

On the flip-side, it resulted in higher rents, in “food inflation” and higher energy costs. Food, energy/transportation and rents represent the main components of the consumer price index (CPI) of emerging markets, in the case of China totaling 60%. Due to the higher CPI, employees continously demanded higher wages and had high inflation expectations for the coming years. Central banks had to raise interest rates to record highs to stop higher wage demands. India’s repo rate rose to 8.5%, while Brazil had to hike to 12.5% in 2011. Still in 2013, the Chinese lending rate is at 6%, a considerable disadvantage for businesses. The Fed tried to reduce the competitiveness gap between emerging markets and the United States with a weaker dollar. With a backwards-looking perspective, one could believe that it managed to reduce the spread between higher U.S. wages and the ones in developing nations. But we do not know if this was intentional. However it did one thing: the central bank helped to reduce global imbalances especially on the wage level.

According to the annual report on salaries of ECA International , average salary increases in Asia / Pacific will be 6.2% this year [2013],… between 2.3% and 12% more than the previous year. This is more than double the rates in Northern Europe or the U.S. …. In places like Indonesia, the union and protests and authorities are forcing companies to be more generous to employees. In November last year, for example, the minimum wage in Jakarta suddenly rose 44 percent

Average pay in Asia almost doubled between 2000 and 2011, compared with a 5 percent increase in developed countries and about 23 percent worldwide, according to the International Labour Organization in Geneva. The gain was led by China, where average remuneration more than tripled during the period. Southeast Asia is catching up, with new minimum pay levels in at least five nations eroding companies’ ability to make cheap toys, clothes and furniture…..

The Thai baht, Philippine peso, Indonesian rupiah and Malaysian ringgit all have gained more than 16 percent against the U.S. dollar in the past four years. China’s yuan is up 10 percent.

“When you add to the appreciation trend in the yuan, it means that China’s export prices will probably continue to rise,” said Dominic Bryant, senior Asia economist for BNP Paribas in Hong Kong. (Bloomberg)

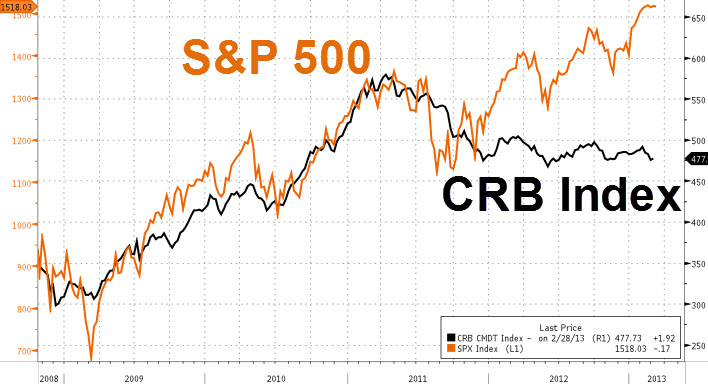

In September 2012, the Fed introduced “QE3”, an “unlimited” version of quantitative easing, primarily addressing the depressed U.S. housing market with “unlimited” purchases of mortgage-backed securities. For the first time since 2008, a measure really worked; the main reason was that with European austerity and Asia slowing, there was no better place to invest than in the United States. At the same time, the Fed provoked the same effect as Volcker in 1982, lending rates for emerging markets rose strongly and posed threads for the competitiveness of the developing nations.

However, thanks to foreign currency reserves, Emerging Markets were far more independent from U.S. monetary policy than South America was in the 1980s. Asian central banks started to ease policies again from summer 2011 on.

There was no “currency war”: funds did not flood into emerging markets this time, but into stock markets of developed economies, while stocks of emerging markets lagged in 2013. Many may call the debasement of the yen a “currency war”, but it reflected just the rising Japanese trade deficit and the move into the sharply improving Japanese stock market, leveraged by yen borrowing. The reason why Japanese stocks improved is clear: almost zero percent lending rates and a cheaper yen made their companies far more attractive than the ones of emerging markets.

China Foreign Direct Investments and exports 2007 until 2012 (source Financial Times)

The Chinese authorities kept a grip on the real estate market with higher rates, an implosion would threaten their power.

But the easing period in Emerging Markets quickly finished, when the U.S. showed signs of recovery. Central banks in the emerging markets understood that fighting inflation is far more important than maintaining global growth. This tightening happened despite outcries from the international press that the Chinese should consume more and help finance the weak European member states.

In early 2013, the “Banco de Brazil” rates were at 7.25% and constitute a considerable burden for businesses. Argentina’s notorious inflation led to 15% rates and the Bank of India kept rates at 7.75%, China at 6% and Indonesia at 5.75%. The Bank of Russia’s 8.25% is, according to oligarch Deripaska, a considerable issue for Russian businesses.

The Volcker Moment Redux

Some people think that the longer-term negative influences of QE2 on emerging markets and the positive stimulus of QE3 for the U.S. could be a sort of “Volcker moment redux”.

A growth-led dollar bull run for at least the next two years is on the cards, raising the spectre of an emerging market crisis, George Magnus, economic adviser to UBS, has warned. In a February 25 report, Magnus fires a shot across the bows of emerging market bulls, who cite strong relative growth prospects, long-term currency appreciation pressures and asset base expansion as reasons why emerging markets can withstand volatility in the US exchange rate and government yields.

He argues a stronger US dollar, accompanied by higher US real rates and slower trend growth in China, threatens to trigger a disorderly unwinding of portfolio flows to emerging markets and credit-negative current account weakening. He writes: “It seems complacent to imagine that the capital flows that have poured into emerging market real estate, local currency bond and equity markets, and piled up in their central banks, will be benign when they reverse as the US dollar appreciates. If the idea of a strong US dollar becomes more widely shared, this is likely to be a trigger of financial instability, much as it was in the previous two bull market cycles [1978-1985 and 1992-2001].”

(source Euromoney)

The disinflationary cycle has started in emerging markets

Banco de Mexico’s Carstens is the first to decide to fight slow growth with lower rates and risk higher inflation. Mexico is the first developing economy that has started to lever on disinflation in emerging markets.

Longer-term exceptions are Thailand and Malaysia with rates at 3% or less. See here the full list of global rates. The following graph shows how due to the slowing in emerging markets the global demand for commodities is falling, while optimism in the United States – driven by positive consumer sentiment at last and not by cheaper oil – pushed the S&P 500 upwards.

No Need For Raw Materials to Grow (source Zerohedge)

While the strong inflation in emerging markets has ended, an inflationary cycle in some developed countries led by the United States and some Northern European countries around Germany has just started.

In the second part of this essay we will present evidence that many emerging markets have lost large parts of their competitive advantage. We agree with George Magnus and think that certain economies like India, Argentina or even Brazil may quickly face currency crises. However other ones like China, Malaysia or Thailand are still able to maintain their position. Due to some structural weaknesses in the U.S. and the accumulation of capital in China and others we do not see a complete repetition of the years after the Volcker moment. Sooner or later they will be able to cut rates and help businesses again.

Moreover we explain why the future investment opportunities are countries with current account surpluses like Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and (possibly even) Italy, but not most parts of the emerging markets.

2 comments

trader

2014-01-12 at 21:33 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

I thought currency crisis in Argentina and India already started?

currency crises

Read more at: https://snbchf.com/2014/01/volcker-moment-redux/ | SNB & CHF

currency crises

Read more at: https://snbchf.com/2014/01/volcker-moment-redux/ | SNB & CHF

currency crises

Read more at: https://snbchf.com/2014/01/volcker-moment-redux/ | SNB & CHF

DorganG

2014-01-13 at 19:12 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

Sure, it has started. Only in March 2013 it had not yet. I anticipated it. There will be a follow-up post soon.