The Money Market Event is the biggest feast of the Swiss National Bank and a selected list of money managers that work together with the central bank. It is initiated by important speeches and ended with a generous buffet dinner. In the first speech, Andrea Mächler addressed three points:

- The expansion of the SNB balances sheet as measure against the so-called “strong franc” in a historic perspective.

- How the SNB takes over currency risks from the private sector.

- Details on the balance sheet expansion: Which kind of assets and liabilities does the SNB possess?

My annotations are marked in bracket [ and ].

Welcome to the SNB’s traditional Money Market Event in Zurich. I am delighted that so many of you have responded to our invitation. A year ago, you were welcomed here by Fritz Zurbrügg, my colleague in the Governing Board and predecessor as the Head of Department III. It was only a few weeks after the minimum exchange rate had been discontinued, and monetary policy was the hottest topic in town.

This year, I will focus on the Swiss National Bank’s investment policy. In the past few years, the SNB has become a big asset manager. Consequently, I want to look at two questions today. First, what are the reasons for the significant increase in our foreign currency invest ments? Second, how does the SNB handle these foreign currency investments?

However, I can’t leave monetary policy out completely. I will thus comment on our current monetary policy at the end of my speech.

Balance sheet expands due to measures against strong Swiss franc

In the past few years, the SNB’s balance sheet total has risen sharply. Since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, it has multiplied by a factor of six. At the end of last year, it came to around CHF 640 billion, or almost exactly the value added by the Swiss economy in 2015. The growth in the balance sheet total is attributable to a rise in Swiss franc liquidity and an expansion of our foreign currency investments.

This brings me to my first question: how did the increase in foreign currency investments come about?

The short answer is that it is the result of monetary policy measures which the SNB takes to maintain appropriate monetary conditions in Switzerland. Thus, foreign exchange market interventions, which the SNB has been using to counter the appreciation of the Swiss franc since spring 2009, have led to the increase in foreign currency investments and, in turn, the SNB’s balance sheet total. Thus a high level of foreign currency investments is not an objective in itself. On the contrary. It forms an integral part of monetary policy.

As observers of our monetary policy, you will be familiar with the reasons why we are active in foreign exchange markets.

In the wake of the crisis which encompassed global markets eight years ago, demand for safe investments, including Swiss francs, rose rapidly.

At the end of 2008, this led to a first significant appreciation in the Swiss franc.The SNB took a series of measures to increase liquidity in the banking system

and prevent a further strengthening of the Swiss franc against the euro, including, from spring 2009, interventions in the foreign exchange market.

A certain stabilisation of the Swiss franc exchange rate took place in 2009.

|

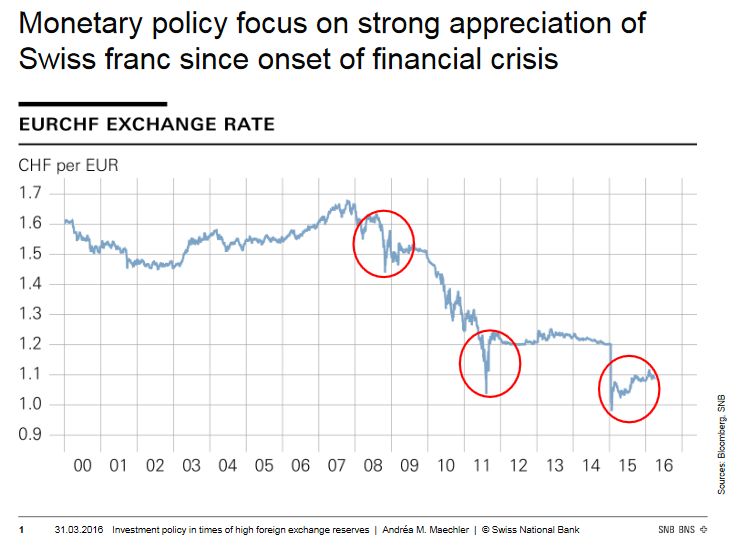

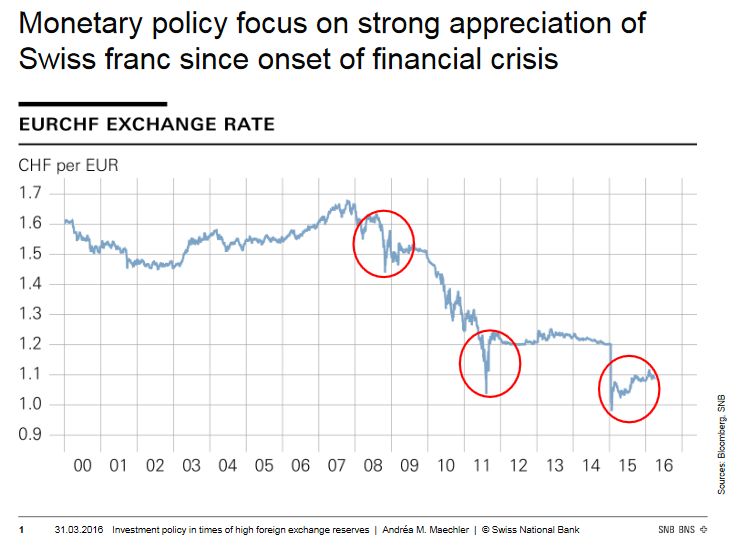

Slide1:

______________________________________________________

- 2009: EURCHF was around 1.50

- Spring 2010: tensions on the financial markets with the Greek debt crisis

—> another global flight into safe investments.

- 2011: CHF under substantial upward pressure against all major currencies,

- August 2011: CHF reaches parity against the euro

- September 2011: SNB introduces the 1.20 EURCHF minimum rate

enforcing it by “unlimited” foreign currency purchases.

- For more than three years, the minimum exchange rate

as an “exceptional and temporary instrument”

- to counter a broad-based and extreme Swiss franc strength.

- It stabilised the situation and gave the Swiss economy time to adjust.

|

|

However, in 2014, exchange rate conditions began to shift once again. Expectations that the US central bank would soon lift interest rates had been increasing since mid- 2014. The European Central Bank, meanwhile, indicated towards the end of the year that further extensive monetary policy easing measures would be necessary in the euro area. Against this background, the US dollar began to appreciate and the euro came under strong downward

pressure. Because of the minimum exchange rate, the Swiss franc also depreciated against the US dollar. This caused pressure on the minimum exchange rate against the euro to rise very substantially and made increasingly large interventions necessary. Instead of broad-based Swiss franc strength, we were faced – to an ever greater degree – with pronounced euro weakness.

In this fundamentally changed environment, the minimum exchange rate was no longer sustainable. Had the SNB attempted to maintain the minimum exchange rate, it would have lost control of its balance sheet and, with it, monetary conditions in Switzerland, because of the increasing magnitude of the interventions. Consequently, on 15 January 2015, the SNB discontinued the minimum exchange rate. To cushion the upward pressure, the SNB simultaneously lowered the interest rate on sight deposits to –0.75%. It also stressed that it was willing to intervene in the foreign exchange market as necessary.

These were no empty words, as can be seen from our foreign currency purchases, which amounted to more than CHF 86 billion last year. A large portion of these occurred during the period immediately before and after the discontinuation of the minimum exchange rate. The Swiss franc initially shot up after the discontinuation, but then stabilised. Since May 2015, it has weakened again slightly. More recently, the Swiss franc exchange rate to the euro was about 10% above what it had been shortly before the discontinuation of the minimum exchange rate. Our willingness to intervene in the foreign exchange market as necessary was – and remains – an important element in countering the excessive strength of the Swiss franc and the associated negative impact on both the economy and price stability in Switzerland.

How are our foreign currency purchases and the Swiss franc exchange rate related to the expansion of the SNB balance sheet? I will explain this using the financial account and current account. The current account covers, first and foremost, goods and services trade with other countries and cross-border income flows. For half a century, the Swiss current account has regularly shown a surplus. There are two main reasons for this structural surplus.

First, Switzerland is a net exporter; it produces more goods and services than are demanded in the domestic market. Second, the Swiss hold substantial assets abroad, upon which they earn interest and dividend income.

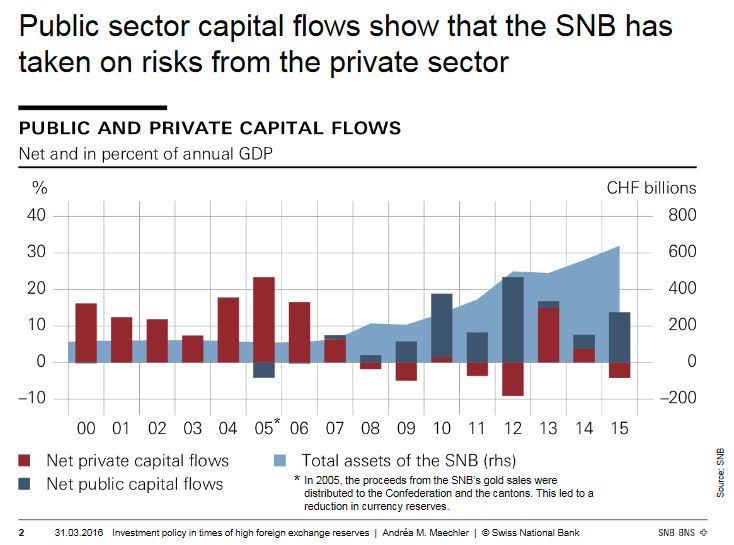

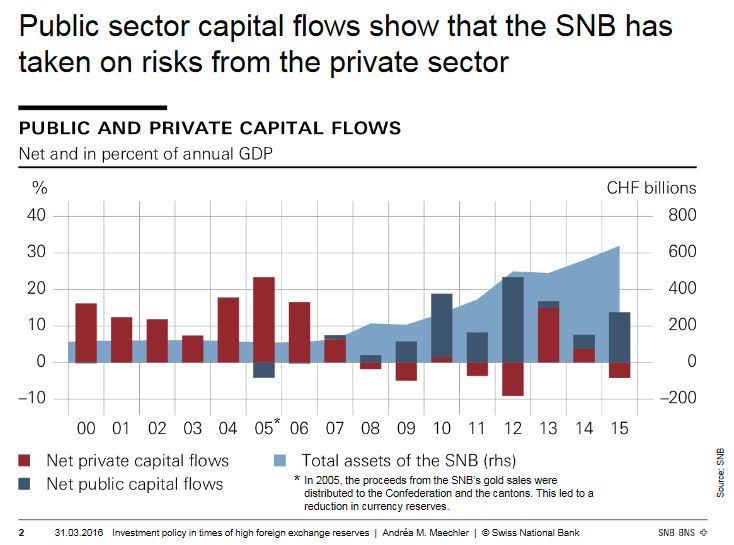

Slide2:

__________________________________________

Items:

- Earnings from foreign trade and

- interest and dividend and

- income from foreign assets

(1), (2), (3) are usually reinvested abroad.

[Mächler means in particular the years between

1995 and 2007, before things were differerent]

Recorded under capital exports

- private sector in the financial account (red bars)

- Until 2007, the private sector exported

almost the entire current account.

[Corrected from “financial account”] |

|

This changed fundamentally after the beginning of the global financial crisis in 2008. Uncertainty increased noticeably. Swiss companies were no longer investing their earnings from export business abroad to the same extent, and were instead increasingly repatriating them. Moreover, a growing number of investors, including institutional investors and private banks, sought the security of Switzerland. Consequently, demand for Swiss francs rose rapidly so that the Swiss franc, at times, was overvalued to an extreme degree.

To counter the strength of the Swiss franc, the SNB began purchasing foreign currency against Swiss francs in the foreign exchange market. In statistical terms, this meant it was exporting capital, with the result that public sector capital exports increased.

This can be seen from the blue bars in the chart. Without these interventions, the Swiss franc would have appreciated even more, with correspondingly negative consequences for the economy and for price stability in Switzerland [with price stability, Mächler indicates that consumers have to pay more and not less. She does not like deflation].

This also means that, with its foreign currency purchases, the SNB has, for some time now, taken onto its own balance sheet the currency risk which the private sector is no longer willing to bear.

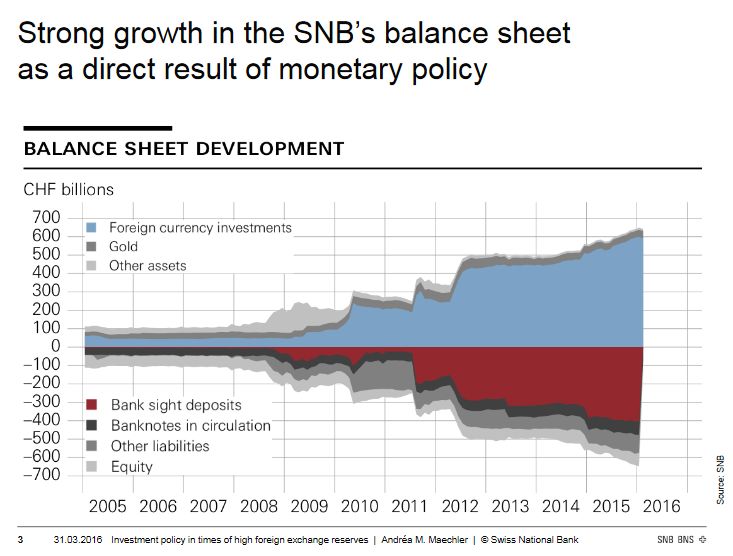

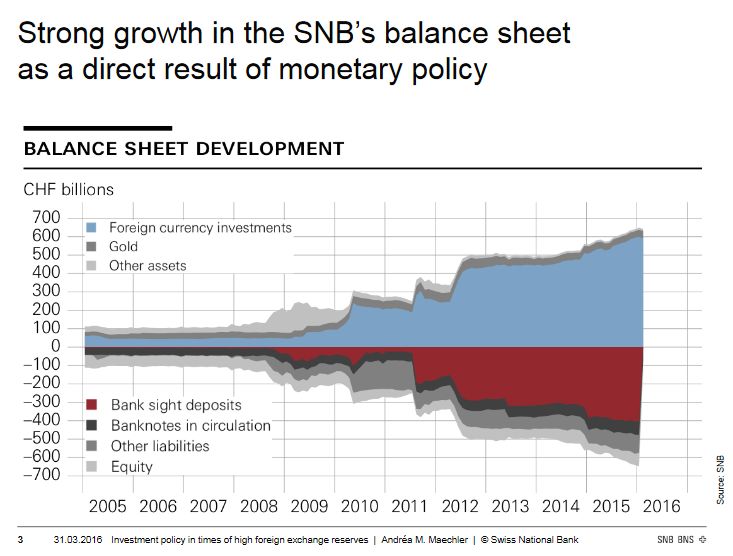

Slide3: Details of the balance sheet.

_______________________________________________________

Assets: mostly foreign currency investments (light blue)Liabilities: Foreign currency purchases also lead to an increase in

CHF liquidity,i.e. a rise in the monetary base. (red area)[This is old-fashion economic language.

Mächler means here that the SNB increases its debt

to banks in order make the Swiss franc weaker]

_______________________________________________________ |

|

Thus, the SNB’s foreign exchange reserves do not represent equity, or ‘true’ assets since they are offset by liabilities.

They have come about through money creation [with “money creation”, Mächler means the increase of central bank debt] as part of measures required for monetary policy purposes.

Consequently, they should be at the disposal of monetary policy at all times. For instance, when capital flows normalise sustainably, we can assume that the SNB balance sheet total can be reduced again in the long term.

However, the level of SNB foreign currency investments will remain high for as long as required by monetary policy. If necessary and reasonable from a monetary policy point of view and if the benefits exceed the costs, the SNB will further expand its balance sheet in future and accept the associated risks.

She was born in Geneva in 1969. She studied economics at the University of Toronto, and then at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, where she obtained her Master's in International Economics. Following a period of study at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Public Administration in Lausanne, she obtained her PhD in International Economics from the University of California, Santa Cruz in 2000.

See more for 1) SNB and CHF