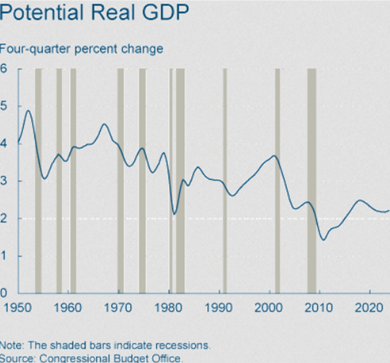

Update 2014:

A little challenging comparison with Real GDP growth in the United States:

Source: Margaret Jacobson, “Behind the Slowdown of Potential GDP”

March 2013

Why being underweight European equities has been the gift that keeps on giving

Via Michael Cembalest, CIO JPMorgan,

Let’s start with the good news: Italy has one of the best fiscal accounts in Europe (its pre-interest budget is in surplus), its current account is in balance (mostly a reflection of a collapse in imports), and Italy finances a lot of its debt on its own without too much reliance on foreign investors (Italy’s Net International Investment Position, a proxy for such reliance, is at -20% of GDP compared to -90% for Spain).

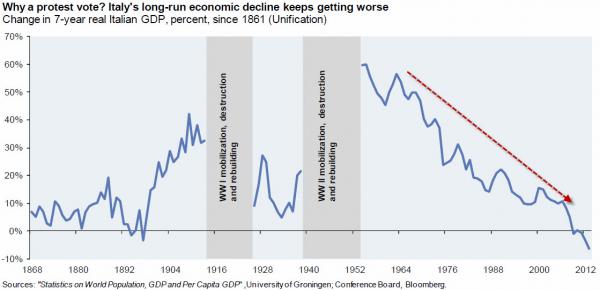

However, growth has been very poor: by the end of 2012, Italy overtook Japan with the worst real GDP growth of all advanced economies since 1991 (0.79% per year, an amazing and sad distinction). Italians are clearly getting tired of austerity against a backdrop of no growth, and around 25% of them voted for a party which reportedly supports renegotiation of Italy’s debt, a referendum on the Euro and a break-up of large Italian state-owned companies (the 5-star movement). The protest vote cast by many Italian citizens this week can perhaps be best understood by looking at the chart below. Other than wartime, the last few years in Italy have been the worst for growth since Italian unification in 1861.

The problem for Italy is that the austerity is not going to end, a consequence of having too much debt (120% of gdp, to be exact), so large that Italy is the world’s 3rd largest sovereign debt issuer despite being 10th in terms of purchasing power. Countries with that much debt generally have to run a budget surplus before interest, since interest payments are so large. Italy has done exactly that, running a cyclically-adjusted primary surplus consistently since 1992. That leaves little room for counter-cyclical stimulus when growth is weak, or when structural reforms create a temporary drag on growth. To be clear about this, the multilateral borrowing facility (the European Stability Mechanism), the lend-against-anything-that-moves policy of the ECB and the commitment by the ECB to purchase government debt (the Outright Monetary Transactions program) all substantially reduce the risk of sovereign and bank defaults, not just in Italy but across all of Europe.

EU governments and central banks have provided 800 billion Euros so far to finance foreign investors fleeing Italy and Spain, and could provide a lot more. But it is getting harder (particularly after last year’s EU equity rally) to dismiss the social and political costs Southern Europe is paying to keep the Euro. In my view, the old system was messier with its periodic bouts of inflation and devaluation, but worked better for Southern Europe given its structural competitiveness gaps with the North, and its own internal fiscal transfer dynamics. Some believe Europe is on a long journey to further integration; I think it is just as likely that parts of Europe are on a long and painful journey to discover that a single currency has more costs than benefits in the long run.

As for France, the recent spat between a US tire company CEO and French Industrial Renewal Minister Montebourg got a lot of publicity. There is hyperbole being thrown around by both sides, but we do find evidence that France has created a worker’s utopia compared to many other countries. Last year, we showed a chart indicating that France has the most worker-friendly environment of 40 countries analyzed (November 7, 2012), a computation based on labor force participation, ease of hiring and firing, retirement age as % of life expectancy, working hours per year, vacation days, linkage between pay and productivity, unemployment benefits as % of wages, etc. France has been trying to enact reforms, but my sources differ sharply on their potential for success. France has lost a lot of ground to Germany since the Euro was launched, and I’m not sure Industrial Renewal ministers can change that. Here are some stats from Bernard Connolly at Hamiltonian Advisors:

- The share of French corporate profits in gross value added is the smallest of the six major EU countries, and falling

- While Germany has maintained its share of world exports, France has lost one third of its share since the Euro was launched.

- France’s current account deficit is around 6% of GDP (in other words, very large) after taking into account depressed consumption due to high and rising unemployment

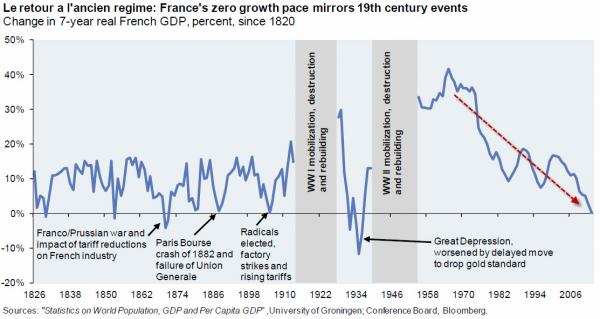

The growth challenge for France is something we will have to watch as well. It’s not as bad as in Italy, but as shown below, other than during wartime (see Appendix on why wars are excluded from charts like this), this has been a very bad stretch for French growth. A period of no growth over 7 years in France is something seen more frequently during the 19th century. It was also seen during the 1930’s when France stuck to the gold standard longer than other countries did, and paid a price. The are some parallels between the gold standard in Europe in the 1930’s and the binding constraint of today’s currency union.

European equities might get cheap enough at some point, but last year the valuation gap vs the US narrowed, particularly among financial stocks, and they don’t look cheap enough yet. We don’t know where things will go from here in Italy. Europhiles predictably believe that a grand Italian coalition will form and work together to avoid another round of elections. I understand why, since in Greece, a second round of elections simply ended up increasing fringe party votes. Perhaps what Italians really want is a little less fiscal austerity, and are asking their politicians to figure out how to do it without upsetting German demands for more. I can see Germany agreeing for some forbearance before its own elections to avoid a larger problem.

All things considered, from an investment standpoint, caution continues to be warranted. Our 2013 Outlook included the following at the end of the Europe section: “By primarily relying on unemployment and wages to restore competitiveness, Europe is taking the road less traveled and remains an economic and social experiment of the highest order.” Not much has changed since. As always, it’s important for investors to avoid over-extrapolating macro issues when there are opportunities to be had in financial markets. However, while European companies earn a substantial amount of revenues outside Europe, their domestic exposures and exposures to other weak EU countries are too large to ignore.

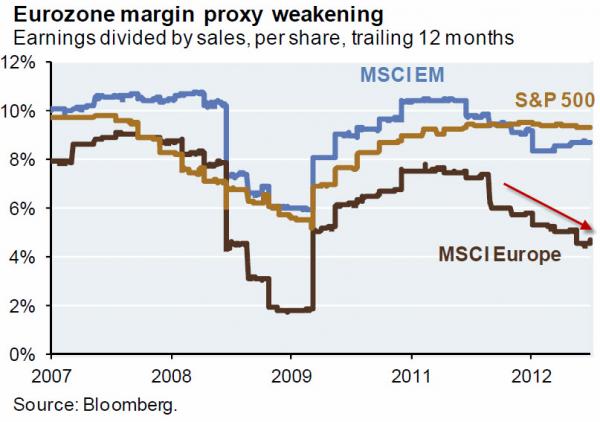

The last chart shows a proxy for profit margins by looking at earnings relative to sales for the 3 major regions. As shown, problems in Europe appear to be taking their toll on EU corporate profitability.

See more for