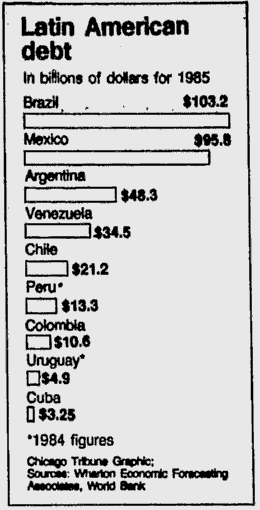

The next financial cycle took place from 1981 to 1986: Thanks to high US interest rates and an oil glut, the US dollar was strong, and Latin America lost a decade.

The phase between 1978 and 1985 was characterized by an oil glut, slow global growth, high interest rates, the strong dollar and repatriation of funds from emerging markets, in particular from Southern America.

The main reasons were the South American debt-financed growth during the 1970s and Volcker’s high interest rates in the 1980s. The 1982/1983 U.S. recession let many Latin America countries go nearly bankrupt and some American banks to the verge of collapse. Due to low global growth and the discovery of new resources, an oil glut arose. From these weak prices the U.S. could take profit and had the strongest growth, while countries like Germany that depend more on global exports had a weak phase. For Southern America, however, this period was the bust leg of the credit cycle, the so-called “decada perdida” , the lost decade. Interest rates were too high to allow investments.

In the first part of the decade the United States lived a boom, in particular because oil prices collapsed with higher supply and productivity increased, when wages had stopped their rapid increase.

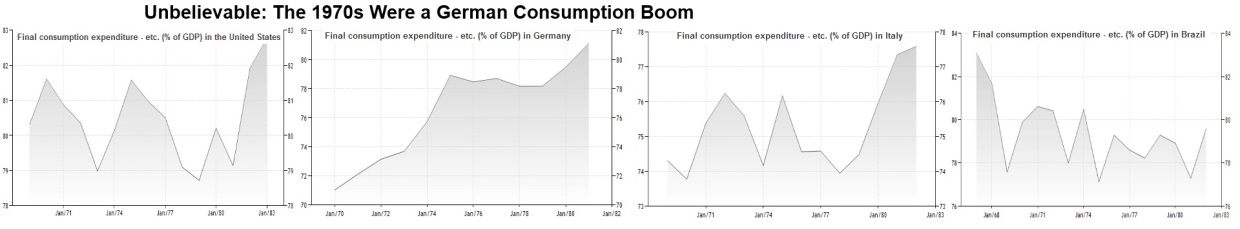

The German Consumption Boom

During the 1970s, Germany saw a strong boom that ended with higher inflation and high asset prices. Similar to Switzerland, Germany had a lighter form of the wage-price spiral: wages did not rise as quickly as in the U.S. Instead asset prices strongly appreciated. Keynesian theories and people’s desire for a higher living standard drove the German consumption part of GDP from 71% to 81% in only ten years. Germany was seen as the best producer in the 1970s, but it due to the excessive consumption phase, it is replaced by Japan in the 1980s.

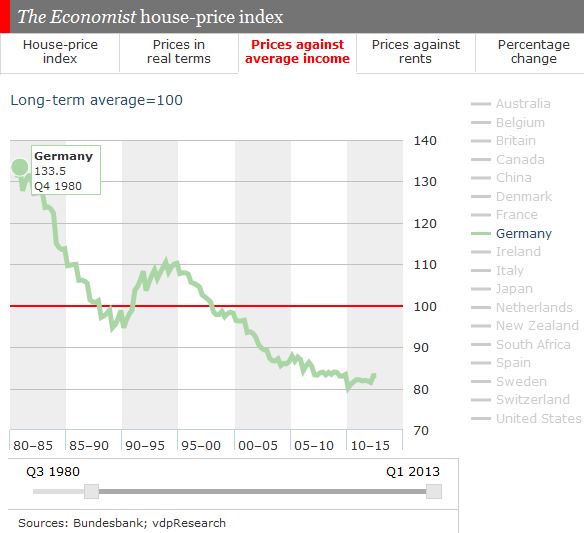

30 Year-Long German Housing Bust after the 1970s Boom

During the 1970, Germany stood for the country that could resist inflation thanks to moderate unions, productivity gains, immigration and a stronger and stronger German Mark. Home prices in Germany reached a top of 133.5% against income in the year 1980. But then, inflation-adjusted (real) home prices fell by 24% from 1980 to the year 2009/2010, the price to income ratio fell from 133% to 80%.

In a first phase the price to income ratio declined to 95% in 1989. With the boom of the German reunification, the ratio rose to 111%. But higher supply from Eastern Germany and the following period of the “sick man of Germany” let the ratio fall to 80.1% in the year 2010.

Despite the “great recovery” of the German economy since 2009/2010, the ratio has increased only to 83%: one reason is that income is rising by 3% to 4% per year.

Response of monetary and fiscal policy:

In the Plaza Accord of 1985, major central banks weakened the dollar. Higher investment and production and lower consumption and the weaker dollar drove investments into Europe and Japan.

In the following years, strong Japanese growth went parabolic and generated a huge asset price bubble.