On this page we show that:

- Inflation expectations and wages drive the behaviour of the Fed and Treasury bond yields.

- Excessive wage increases lead to recessions, more or less voluntarily caused by central bank tightening.

- Central banks pin down the short end of the yield curve, while financial-market participants price longer-dated yields.

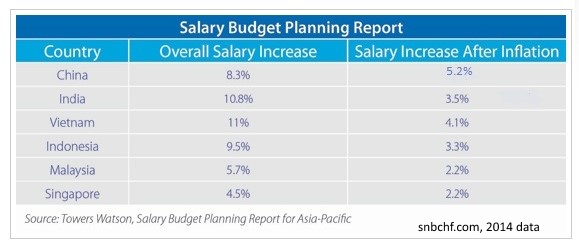

- Some Emerging Markets seem to be copying the strong wage increases and inflation that the West lived through in the 1970s.

- Quickly rising higher wages in Emerging Markets may narrow their competitive advantage against the U.S. and Europe.

- Therefore the “secular stagnation” in the West might not last as long as expected.

Updated version with most recent BEA data and further explanations.

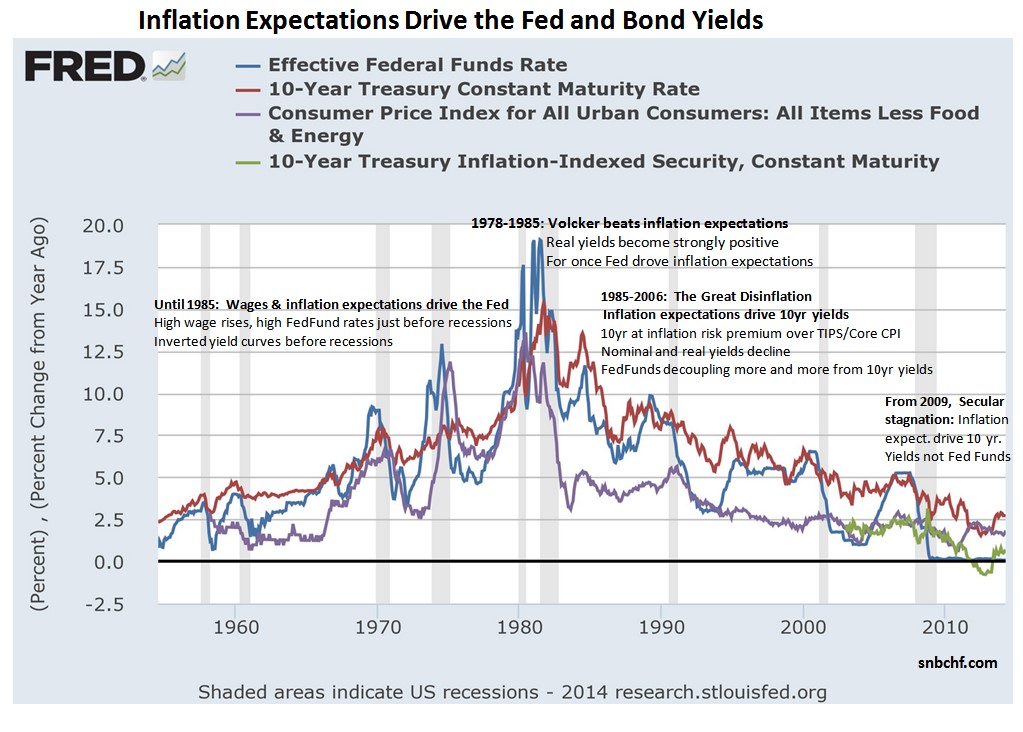

In most periods, inflation expectations and wages remain the main drivers of US bond yields. Inflation and its early indicators, like money supply or inflation expectation surveys, are the main determinants of the Fed’s bbehavior The inflation expectation surveys are often closely related to wages. Expected wage growth is often met by effective wages and inflation after some time.

Until 1985: Wage developments and inflation expectations drive behavior of the Fed

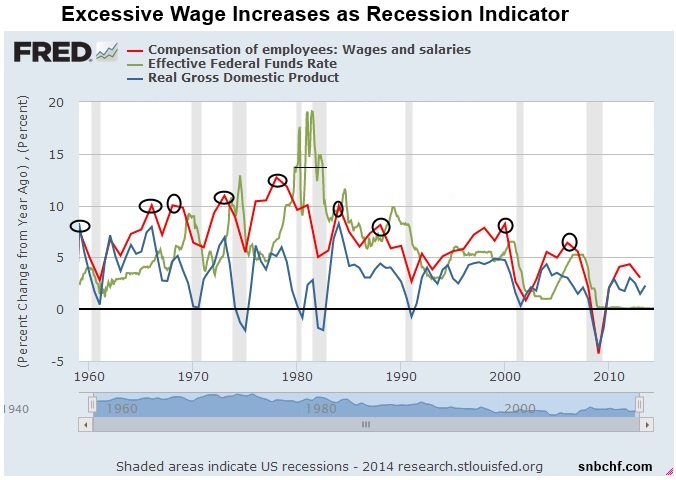

Until 1985, inflation expectations and wage development drove the behavior of the Fed: when wages rose too quickly and when those were translated into higher sales prices and high price inflation, then the Fed had to hike rates. Consequently credit and investments became more expensive, and costs got too high. Entrepreneurs reacted and fired workers. Thanks to higher unemployment and a recession, competition in the labor market increased. Inflation expectations and the speed of wage improvements fell again. With the recession the Fed restored the equilibrium in GDP growth between growth attributed to rising company profits and growth attributed to rising wages. The following graph shows how excessive total wage payments were an indicator that predicted a recession or a considerable slowing. The NAIRU, aka an unemployment rate that is too low to be able to stop inflation, is closely associated with that point. When we speak of total wage payments this includes two effects: higher pay and more people in the labor force.

Until the 1960s, a 9% nominal increase in total wage payments predicted a recession. In 1978 this value rose to 13%, sustained by rising oil prices and spending as well as quickly rising wages in Europe, including even Germany. In 2005 this indicator only achieved 6.5% higher nominal wage payments but it was already enough to predict a recession. The parallel movement of the red and the green line shortly before the recessions show how the Fed hikes rates in order to stop the wage excesses.

The Peak of Inflation in the early 1980s

The peak of inflation expectations was in the early 1980s, 10 year Treasury yields topped at 19% during a wage-price spiral. Volcker managed to beat excessively high inflation and wage expectations. When he kept short-term rates high for a longer time, refinancing for banks became expensive. Money supply and today´s unpopular GDP growth driver, called “credit growth” fell again. With lower wage expectations, workers could not anticipate their future earnings with loans like they did before. Furthermore, it reduced the distance between rapidly rising wages in the US compared to countries with a slower “wage hike pace” like Germany and Switzerland. Finally, the dollar stabilized again. The concept called “productivity” = GDP divided by worker and stock markets edged up after years of poor performance.1

Since 1985-2004: Inflation expectations drive bond yields and Fed

From 1985 to 2004, the old picture returned: inflation expectations drove the Fed and bond yields. But now both nominal and real yields fell during the following period that we call here the Great Disinflation. The inflation risk premium, the difference between 10 year yields (red line) and core inflation (pink) is clearly visible. It contracted more slowly than yields so it arrived finally at values close to zero in 2011 and 2012. TIPS (green) are an alternative to core inflation or short-term rates to compute the inflation risk premium.

Since 2004: Fed Funds Rate decouples from 10 year yield

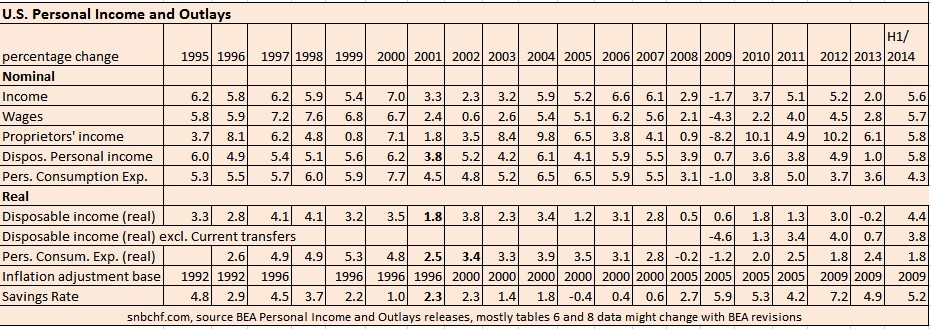

Since 2004, the Fed Funds rate seems to have been completely decoupled from 10 year yields. It moved up and down between 0.25% and 5.5%, but the 10 year yield continued to fall nearly steadily until 2012. The main reason might be aging and the need for more savings, but the weak U.S. savings rate until 2007 does not speak for this hypothesis. The reason is rather high savings in Emerging Markets (EM), what Bernanke called the savings glut. Effectively in Southern Europe, France and partially in the U.S. workers thought that salaries should keep rising nearly as much as they were increasing in China. Germany, Japan and Switzerland, however, decided to leave their labor force competitive. The following BEA data gives some more indications. It shows in particular the point when wage payments rise significantly more than company profits – called here “proprietor’s income”. This point often corresponds to the NAIRU.

The Fed ended the spending and wage hike party based on a housing bubble from 2005 onwards, it hiked the Fed Funds rate. In 2006 and 2007, proprietors benefited from smaller increases in income than wage earners. Economic developments were much more globalized, the boom continued somewhat longer in Europe and in the rest of the world. With higher rates, the U.S. housing bubble had already popped in 2007. Despite a savings rate near zero, the Fed was constrained to lower rates. Easy Fed money combined with continuing U.S. and European spending led to even more investments in EMs and home building in Europe. This investment boom triggered an explosion of the oil price to nearly 150$ in summer 2008. When finally the recession happened, the Fed was completely surprised by its intensity. Many claim that Fed’s years-long easy money increased recession risks, in particcular because it inflated the oil price.

Similar to excessive wage increases, a rapidly rising oil price may also cause a recession. In the 1970s both phenomenons were combined, but in 2008 the oil price and rising household debt were more important.

The Great stagnation

With collapsing U.S. demand during the financial crisis, Europe and EMs massively corrected their desire for investments and spending. The oil price collapsed to 35$ only some months after its 150$ peak. With the so-called Great Stagnation, U.S. wages stopped rising quickly and households adjusted their saving rates from values around 0% before the crisis to more sustainable values of over 5% after it.

EMs, however, continued their wage recovery against advanced economies. Already in 2010, it became clear that thanks to QE1 and Chinese fiscal expansion, EM wages and investments increased far more than in the developed world. This, however, helped to avoid a longer-lasting global crisis. With higher wages, most of the EMs maintained high household savings rates, but company margins in EMs slowly eroded. Chinese stocks could never achieve the highs of 2007 again. The opposite picture in the U.S.: the equilibrium between entrepreneur profits and wage contribution to US GDP growth completely moved to the favo^ur of entrepreneurs (see in table above under “Proprietors Income”). Piketty’s book “Capital in the 21st Century” describes well the symptoms. But Piketty does not really understand that rising wages, inflation and the desire to invest squeeze company profits in EMs and stock market valuations there. Since 2009, EM spending power increased profits of many U.S. companies. Moreover, investments of U.S. firms in EMs do not really contribute to US GDP, while investments in the U.S. remained subdued at least until early 2013. Labor costs in EMs appeared still to be low enough to prefer investments outside of the U.S.

Excessive wage hikes reduce competitiveness of Emerging Markets

But now the picture is changing: Russian GDP was driven by a rising oil price and led to years of low unemployment, rising salaries and higher consumption. But with high borrowing rates and capital outflows, investments have stopped. Missing investments and fear should finally increase Russian unemployment and adjust excessive pay rises. The weak ruble will contribute to make Russian labor competitive again.

Brazilian industrial production is falling due to high inflation expectations and high rates. Some more examples of how much wages in EMs are still rising are here and here. The period of high real wage increases in EMs is ending. In order to remain profitable, firms in EMs are constrained to reduce investments, in particular in the Chinese real estate market. With less global investments and lower global growth, prices for Brent oil and commodities are falling.

Claudio Borio of the Bank of International Settlement speaks of high risks that EM currencies will collapse this year again. This collapse would make their wages in global comparison cheap again but capital should get expensive. We think that it could rise from 5% yield per average EM bond issuance today back to 8% as some years ago. We understand that many EMs are copying to some extend the wage and credit excesses that the U.S. and Europe lived through in the 1970s and early 1980s. No wonder, as for economic developments, in particular for the availability of financing, they were 20 or 30 years behind us. An important exemption from this rule, however, is China. China has accumulated far more capital than any other EM and is able to limit wage hikes thanks to its totalitarian regime and the Asian collective mentality.

We think that there are two types of EMs, the ones with rather autocratic governments and collective societies with sub-ordinance to the entrepreneur, like in China (this is the ETF “FXI”), Vietnam (VNM), South Korea (EWY), Malaysia (EWM) or Bangladesh. Thanks to wage oppression, investments still make sense in these countries.

Other EMs are too democratic or too individualistic, and wages rise too quickly. The major ones are Brazil (EWZ), India (PIN), South Africa (EZA), Turkey (TUR) , Argentina (ARGT) and maybe also Indonesia (IDX). Central banks must often obey political pressure, which leads to a depreciating currency and continuing wage pressure but rising financing costs. The BRICs have finally split, just as Jim Rogers predicted.

For us, wage differences and relative competitiveness drive the world economy and economic cycles. When wages rise quickly in EMs, then there is a big chance that the secular stagnation in the U.S. or in Europe will not last as long as expected.

Read more:

More about bond yield drivers on our page: What determines government bond yields.

- We do not want to discuss here neither technological improvements as most beautiful growth drivers are distributed to employers and employees nor if Free Banking without the Fed would have restored the equilibrium earlier than the Fed did. [↩]