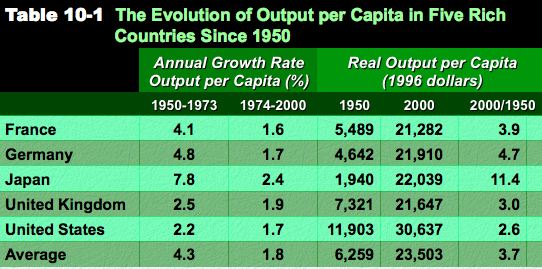

The Bretton Woods time from 1945 to 1966 was a period of strong growth, especially in country like Germany, France, Italy and Japan.

The growth was reflected in the Dow Jones adjusted by CPI:

|

Dow Jones Industrial Average adjusted by the CPI

(Consumer Price Index)

|

|

|

The Bretton Woods time from 1945 to 1966 was a period of strong growth, especially in country like Germany, France, Italy and Japan. - Click to enlarge

In the 1960s Europe especially Germany, but also Japan managed to achieve strong current account surpluses, while in the United States inflation started to rise.

Thanks to that, Germany, Switzerland and Japan managed to accumulate big gold and currency reserves thanks to persistent current account surpluses, while the U.S. reserves continued to fall.

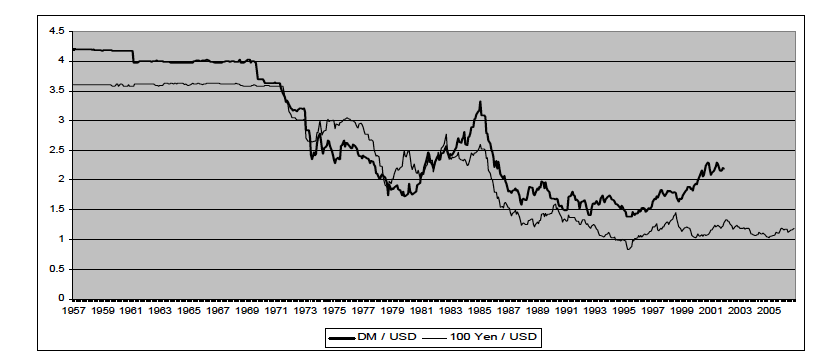

After the US recession of 1960, the world started speaking about global imbalances, excessive German trade surplus and US deficits. German voices wanted Germany to invest the current account surplus in the so-called “third world” instead of creating inflation. In 1961 the dollar was devalued against the European currencies and Japan.

At a period of full employment at the end of the 1960s, salaries adjusted by productivity rose by 6% in the U.S. and even by 13% in Germany. The German Mark was allowed to appreciate by 9.3% in 1969.1

The Bretton Woods time from 1945 to 1966 was a period of strong growth, especially in country like Germany, France, Italy and Japan. - Click to enlarge

Response of monetary and fiscal policy:

Policy makers responded with capital controls, with taxes on German bonds held by foreigners, a separation between official and unofficial exchange rates. Instead of moving to flexible exchange rates in 1970, Germany introduced a tax of 4% for exports and tax incentives for imports.

- Othmar Emminger, Deutsche Geld- und Währungspolitik im Spannungsfeld .. (1948-1975) in: Währung und Wirtschaft in Deutschland : 1876 – 1975 , Online, pp. 33-37 [↩]