Economists commonly explain the rising oil price between 1998 and 2008 as due to the growth of emerging markets. They classify the resulting inflation as demand-pull inflation. We argue that the cost-push inflation of the 1970s was also a reflection of rising global demand. For us, oil prices had remained too low between 1950 and 1970. They had to catch up quickly to the reality: with rising deficits and wages in the U.S. The picture only changed with the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War in October 1973.

Local Cost-Push inflation as Global Demand-Pull Inflation

In part 1 we state that cost-push price increases (or so-called “cost-push inflation”) are not inflation at all, because these higher prices are only temporary. Here we will explain why local cost-push price increases, e.g. in the U.S., is often demand-pull inflation at a global scale.

Today’s oil markets are mostly driven by professional traders that are able to integrate macro-economic supply and demand data. One part of it is expected future demand. The reasons for high oil prices in the year 2008 were the expected high growth and future demand of emerging markets. Hence, the rapid increase to 16% Chinese GDP growth in the first half of 2008 pointed to an oil price of 150$, while the 6% Chinese growth in early 2009 let the price fall to 40$.

From the point of view of the United States, the rapid oil price increase of 2008, represented local cost-push inflation, in particular because the U.S. already had the bursting of the real estate bubble. From the Chinese and European view, higher oil prices in 2008 were justified by rising demand, by global demand pull inflation.

Rapidly rising global oil demand before the price shock of 1973

Due to the financing of the Vietnam war, the U.S. double deficits rose rapidly. The other members of the Bretton Woods system mistrusted the U.S. and started to change gold against the official rate of 35 US$.

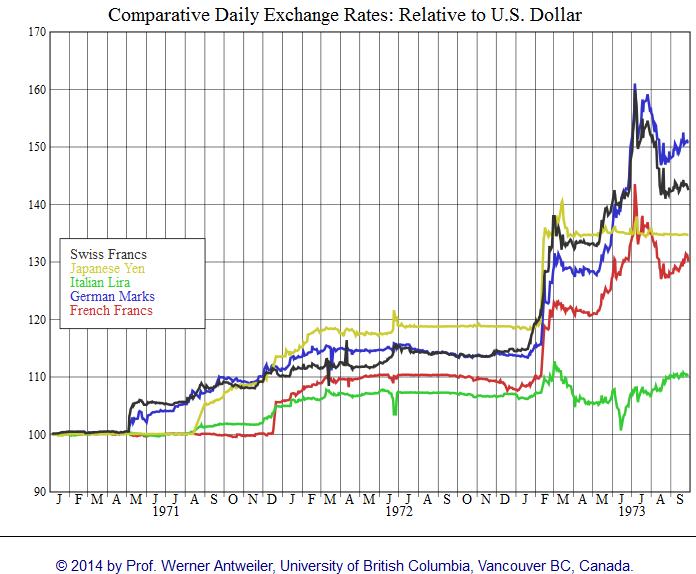

In April 1971, Nixon decided to close the “gold window”. The Swiss franc and the German mark were the first to exit the Bretton Woods system. Then Japan followed in August.

Against the end of the war, U.S. growth was rather sluggish. The Federal Reserve did not hike rates, as would be necessary in a fixed-rate system. To fight slow growth, it lowered rates from 8% in 1970 to 4% in 1973. Funds left the United States and poured into Europe, in particular into countries like Germany that offered high interest rates, stronger growth and lower inflation.

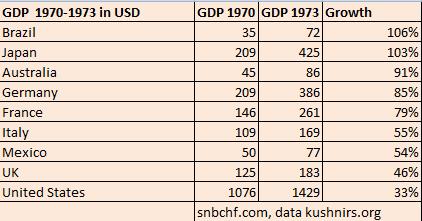

European and Japanese growth managed to clearly outpace the United States. Reasons for the 1970s boom were:

Rising current account surpluses in Germany and Japan, and deficits in the U.S. due to the Vietnam war.

Rising current account surpluses in Germany and Japan, and deficits in the U.S. due to the Vietnam war.- Capital outflows from the U.S., fueled by relatively high U.S. money supply. Bear in mind that, opposed to Austrian theories, the monetary expansion was not the single reason.

- Strong growth but also rising debt e.g. in Brazil or Mexico, countries that did not achieve trade surpluses like Germany or Japan.

- Stagnating productivity in the U.S., but improving productivity in Germany and Japan thanks to CNC technology (read full story).

via Wikipedia http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_Oil_Production_and_Imports_1920_to_2005.png - Click to enlarge

Oil demand was rising quickly. Global car production rose from 29 to 38 million in just three years, the same increase as in the seven years from 1963 to 1970.

Oil supply and prices

Coinciding with the Vietnam war, US oil production peaked. Imports from Arab countries to the U.S. doubled between 1970 to 1973. North sea oil was not available, hence Europeans had to import most of their oil from the Middle East.

From 1947–1970, the real price of oil (in 2009$ prices) had dropped from over 18$ to under 10$. This represented an implicit subsidy for the oil-dependent American economy, but did not let (often dollar-pegged) oil-producing countries even cover the cost of inflation. In many countries oil production was in the hands of Western companies (e.g. Iraqi IPC and the seven sisters that controlled 85% of global oil supply).

The June 1967 oil embargo did not lead to a lasting oil price appreciation for four reasons:

- U.S. supply was still rising.

- Global oil demand was not rising excessively like in the early 1970s, there was no demand-pull inflation.

- The U.S. administration was still guaranteeing price stability inside the Bretton Woods system.

- Arab nations feared negative effects on oil demand and left the embargo with the September 1967 Khartoum Resolution.

They repeated the same mechanism in the early 80s with the oil glut when high interest rates, slow global demand and new supply let oil prices fall.

But between 1970 and 1973 things were different: OPEC member states had finally discovered oil as a source of income. Initially they increased taxes for the Western oil companies and finally nationalized big parts of the oil production.

via chartsbin.com

Read on the following page about the relationship between monetary and political events, FX and oil price movements during the crisis years.

See more for