A collection of several sources showing: Wells Fargo Housing Market Index, Existing Home Inventory, S&P/Case-Shiller, New Home Sales, New Home Prices, Ratio New Homes to Population, MBS Purchases by the Fed, Household Liabilities and Dependency Ratio.

We show charts and arguments in favor of a housing recovery against the counter-arguments.

Most recently many asset managers moved out of gold (e.g. Pictet) The reason was that they believe in a sustained U.S. recovery based on more local oil production thanks to the new fracking techniques and in a recovery of the U.S. housing market.

Pictet did not mention that there is a third important reason: Due to less construction activities and funds leaving countries like China and Brazil, GDP growth in emerging markets has slowed down and therefore global demand of oil and other commodities is weaker. Cheaper oil and gas prices, however, are good for the U.S. consumer and bad for the correlated gold price.

On the other side, Bernanke confirmed that QE3 is unlimited, which is again good for the gold price. When you read this article you will understand why the Fed thinks that U.S. housing needs unlimited assistance.

Take your time to scroll down to see also the counter-arguments from Hugh Smith and Chris Martenson.

Update March 2013:

The result is that overall in Q1 housing starts were 7.2% higher than in Q4 2012. Permits were less upbeat, declining by 3.9% m-o-m to 902,000 (i.e. below starts).

Housing starts have risen sharply over the past two years but remain fairly low by historical standards. Even after the recent surge, housing starts would still have to almost double to climb back to their average between 2000 and 2005. source Pictet

Is U.S. Housing really Recovering?

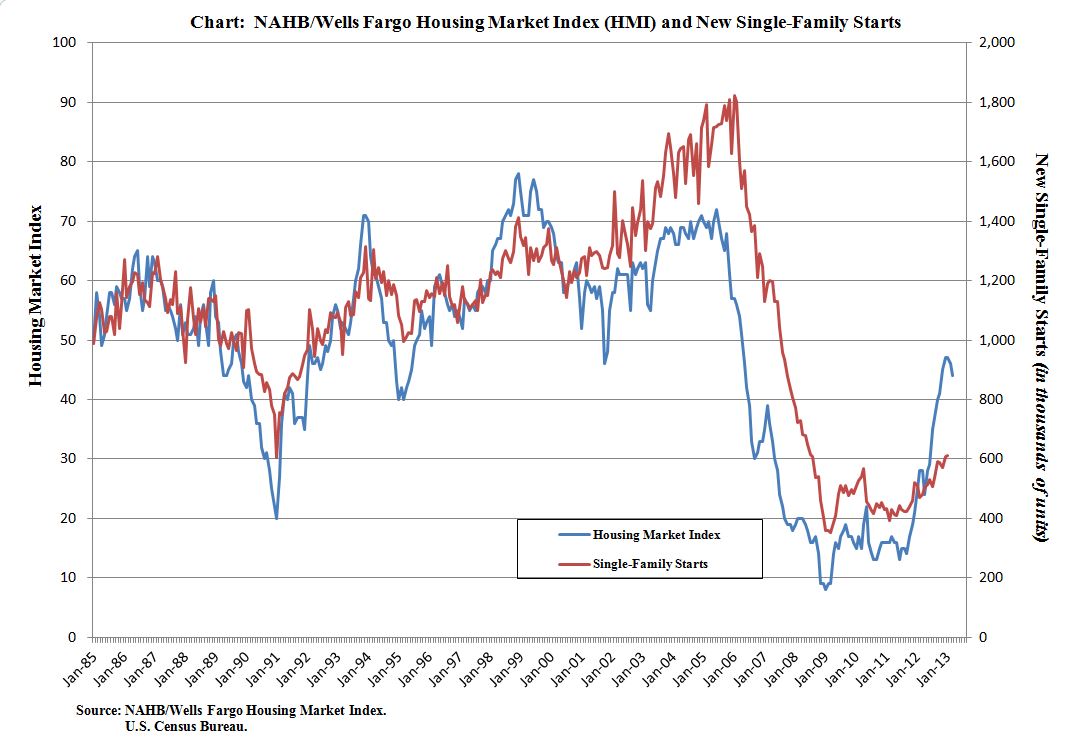

Arguments from NAHB/Wells Fargo:

Builder confidence in the market for newly built, single-family homes paused for a third consecutive month in March, with a two-point reduction to 44 on the National Association of Home Builders/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index (HMI), released today.

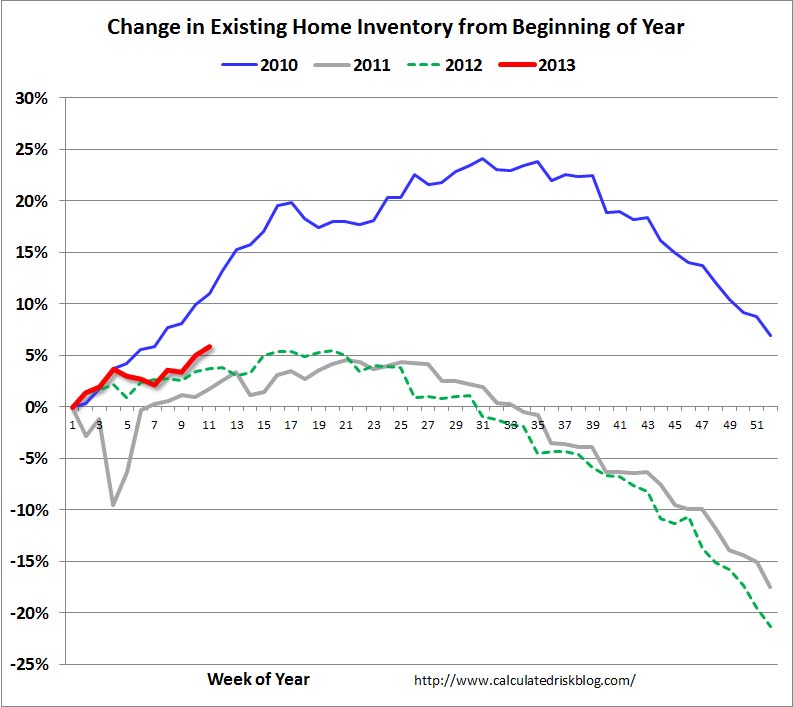

Extracts from calculated risk

In normal times, there is a clear seasonal pattern for inventory, with the low point for inventory in late December or early January, and then peaking in mid-to-late summer.

We clearly see the “Sell in May Come back in October” effect especially in the months from September/October, when more houses leave the market.

Arguments from Global Economic Intersection,

an independent agency that evaluates U.S. home prices and sales.

February 25, 2013

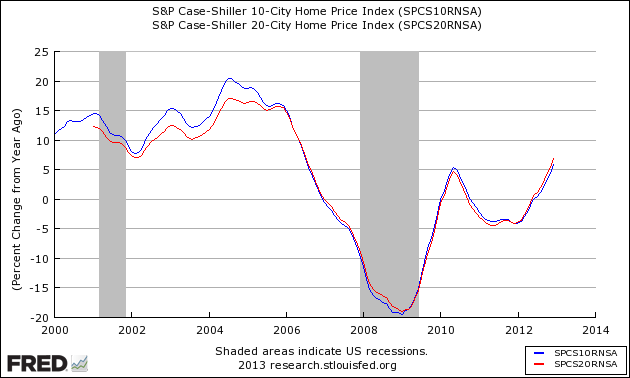

Case-Shiller home price index has shown year-over-year price improvement for the last seven months. The National Association of Realtors and CoreLogic have reported year-over-year home price gains since April 2012. Note the caveats section at the end of this post.

S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices Year-over-Year Change

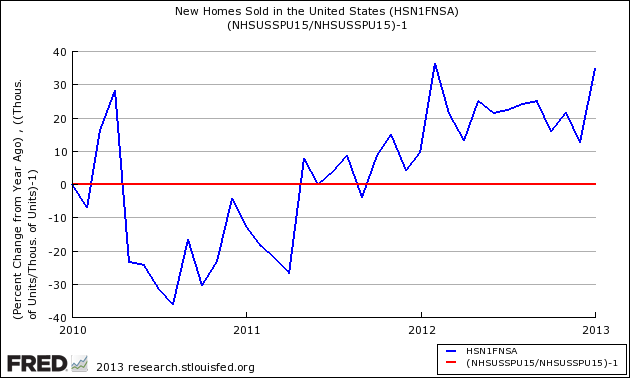

New home sales data for January 2013 was definitely better than last month’s data. We are now seeing one terrible month, and one unbelievably good month.

- January 2013 was the best January since 2008;

- Last month’s data was terrible, and this month’s data is outstanding. Averaging out the data, the 3 month rolling average is at the levels seen in the last 12 months.

- The headline seasonally adjusted numbers say new home sales are up 15.6%, andEconintersect‘s analysis is even better.

Econintersect Analysis:

- sales up 22.3% month-over-month

- year-over-year sales up 34.8%.

- sales down 7.3% month-over-month

- year-over-year sales up 28.9%

- market expected annualized sales of 375K to 383K (actual was 437K – seasonally adjusted)

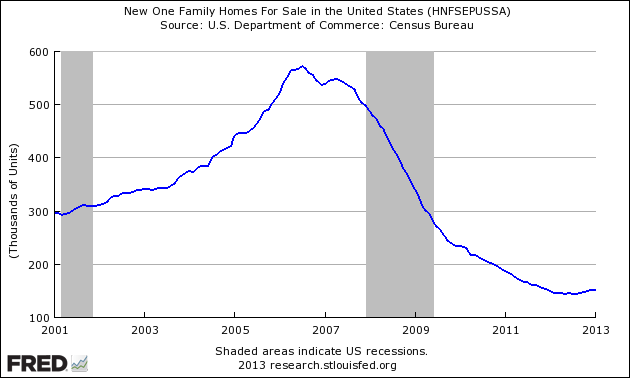

The quantity of new single family homes for sale is now well below historical levels.

Seasonally Adjusted New Homes for Sale

As the sales data is noisy (large monthly variations). The graph below shows the growth trend line although noisy appears to be flat.

Year-over-Year Change – Unadjusted New Home Sales Volumes (blue line) with zero growth line emphasized (red line)

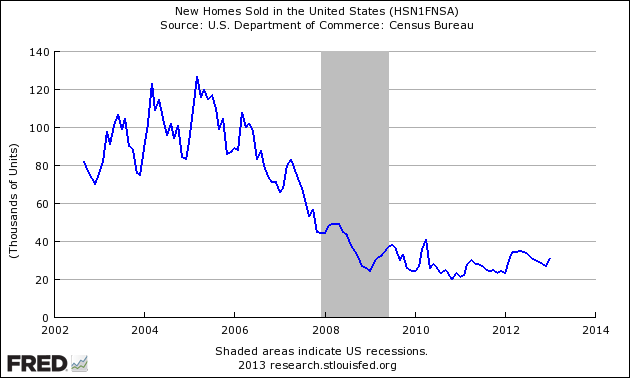

The headlines of the data release:

Sales of new single-family houses in January 2013 were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 437,000, according to estimates released jointly today by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. This is 15.6 percent (±18.9%)* above the revised December rate of 378,000 and is 28.9 percent (±21.7%) above the January 2012 estimate of 339,000.

Unadjusted New Home Sales Monthly Volumes In Thousands

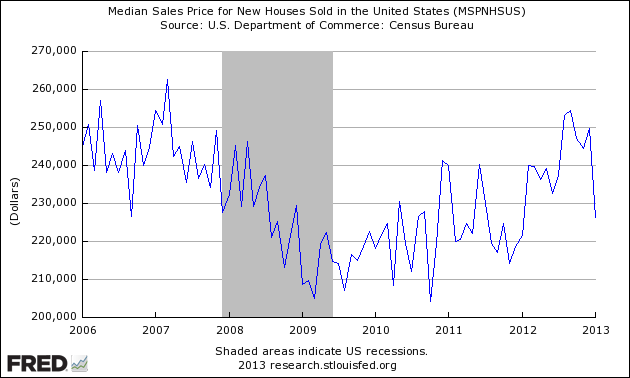

The median sales price of new houses sold in January 2013 was $226,400; the average sales price was $286,300.

Unadjusted Median New Home Sales Price

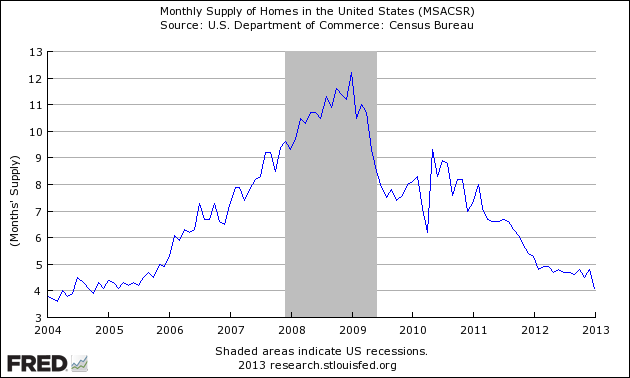

The seasonally adjusted estimate of new houses for sale at the end of January was 150,000. This represents a supply of 4.1 months at the current sales rate.

Seasonally Adjusted – Number of Months of Supply of New Homes at Current Rate of Sales

The unsold supply of new homes has returned to pre-crisis levels.

Caveats on Use of New Home Sales Data

This data is compiled by sampling, and historically has little revision. This data is based on contracts signed – not actual properties conveyed.

As in most US Census reports, Econintersect does not agree with the seasonal adjustment methodology used and provides an alternate analysis. The issue is that the exceptionally large recession and subsequent economic roller coaster has caused data distortions that become exaggerated when the seasonal adjustment methodology uses several years of data. Further, Econintersect believes there may be a New Normal seasonality and using data prior to the end of the recession for seasonal analysis could provide the wrong conclusion. (see Zerohedge’s critique).

Econintersect determines the month-over-month change by subtracting the current month’s year-over-year change from the previous month’s year-over-year change. This is the best of the bad options available to determine month-over-month trends – as the preferred methodology would be to use multi-year data (but the New Normal effects and the Great Recession distort historical data).

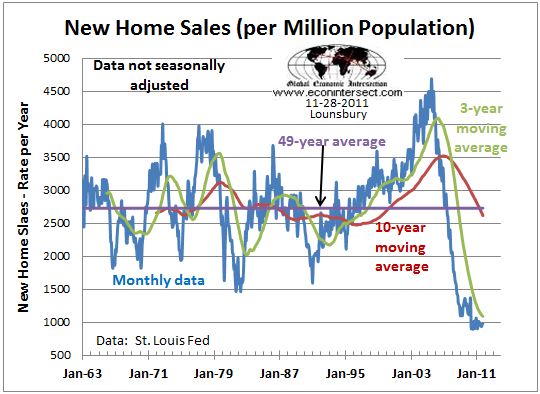

With new home sales at 25% of past rates, whatever your interpretation of the new home sales data is not significant enough to matter. Also the data is distorted by the first home buyer’s stimulus which required contract signing before 30 April 2010 – causing a data bubble and subsequent trough. In spite of Econintersect‘s reservations about the efficacy of seasonal adjustment at the present time, it is interesting to look at the deep history of the seasonally adjusted data.

The broad bottoming process for new home sales in 2010 may not be confirmed or denied for another year or more. The critical factor will be whether the one-year positive trend can continue as year-over-year comparisons will no longer be against the very low sales after the collapse of the tax credit stimulus micro-bubble.

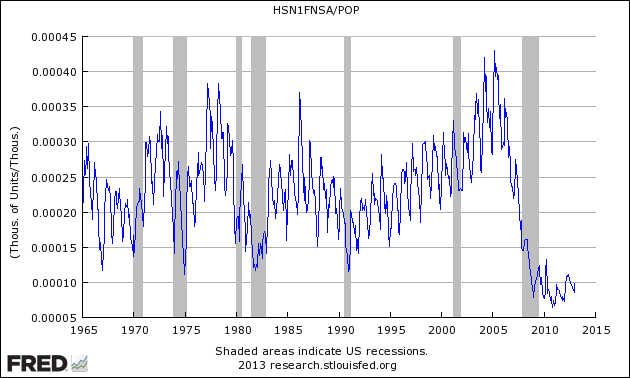

The seasonally adjusted new home sales rate is the lowest it has been for 50 years and has been at that level for almost two years. At the beginning of 1963 the U.S. population was around 188 million. With annual new home sales averaging around 550,000 per year in 1963, the extreme depression in the new home market is evident. In 1963 the rate of new home sales was about 290,000 per 100 million of population. In 2011 the number is about 100,000 per 100 million.

It is more informative to look at these changes over the nearly fifty-year history. The following graph shows new home sales normalized to population from from St, Louis Fed:

Seasonally Adjusted New Home Sales Ratio to Population

The same data is plotted below to include the average for the entire period and two moving averages (graph updated through October 2011):

The bottom line is that the new home market is in an extreme depression and the apparent bottoming process has been dragging on for two years, if in fact the bottom has been reached. Recent review of the Fed 2011 stress tests for banks has a new recession scenario that would see home prices decline another 20% from here. It is unlikely that the attempts to complete a bottom here could hold under those conditions. Econintersect analysis of recession indicators is still not seeing the start of new U.S. recession, however. We can only hope that outlook continues.

The bottom line is that the new home market is in an extreme depression and the apparent bottoming process has been dragging on for two years, if in fact the bottom has been reached. Recent review of the Fed 2011 stress tests for banks has a new recession scenario that would see home prices decline another 20% from here. It is unlikely that the attempts to complete a bottom here could hold under those conditions. Econintersect analysis of recession indicators is still not seeing the start of new U.S. recession, however. We can only hope that outlook continues.

End of Extract From Global Economic Intersection

Counter-arguments from Chris Martenson and Charles Hugh Smith

Given the preponderance of housing in bank assets, household wealth, and the perception of wealth, the key policies of Central Planning largely revolve around housing: keeping interest rates (and thus mortgage rates) low, flooding the banking sector with liquidity to ease lending, guaranteeing low-down-payment mortgages via FHA, and numerous other subsidies of homeownership.

At least three aspects of this broad-based support are historically unprecedented:

1) The purchase of $1.9 trillion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) by the Federal Reserve.

The Fed purchased $1.1 trillion in mortgages in 2009-10 and it recently launched an open-ended program of buying $40+ billion in mortgages every month. Recent analysis by Ramsey Su found that Fed purchases have substantially exceeded the announced target sums; the Fed is on track to buy another $800 billion within the next year or so. This extraordinary program is, in effect, buying 100% of all newly-issued mortgages and a majority of refinancing mortgages.

Never before has the nation’s central bank directly bought almost 20% of all outstanding mortgages this raises the question: Why has the Fed intervened so aggressively in the mortgage market? There is no other plausible reason other than to take impaired mortgages off the books of insolvent lenders, freeing them to repair their balance sheets.

Regardless of the policy’s goal, the Fed now essentially controls a tremendous percentage of the mortgage market….

While housing has recovered to 2010 levels, what is not visible is the collapse in housing’s share of net worth displayed in this chart:

Housing equity as a percentage of total net worth declines when the stock market rises strongly while housing gains at a much lower rate (for example, during the Bull markets of 1952-1968 and 1982-2000) and rises as stock equity falls (for example, 1969-1981) while housing rose. In the 2001-2008 era, both equities and housing both climbed sharply, but since housing is the larger share of most households’ net assets, housing’s rise overshadowed the expansion of stock net worth, causing home equity to rise as a percentage of total net worth.

The collapse of the housing bubble and the stock market pushed home equity as a percentage of net worth to new lows. The subsequent doubling in the stock market has had little effect on the bottom 90% of households, as the top 10% of households own 85% to 90% of all stocks. (Source)

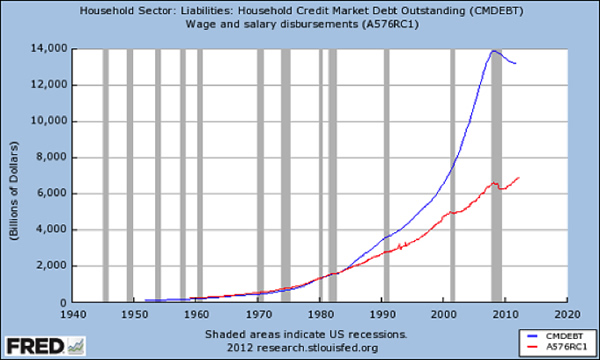

In broad brush, the wealth of middle class of homeowners has been influenced by four trends:

- The stagnation of real income

- A rapid rise in mortgage and other debt

- The use of debt to fund consumption

- The collapse of housing equity as the basis of debt-based consumption

In other words, Federal subsidies and Federal Reserve policies enabled a vast expansion of debt that masked the stagnation of income. Now that the housing bubble has burst, this substitution of housing-equity debt for income has ground to a halt.

This created a reverse wealth effect: The 70% between the bottom 20% and the top 10% have seen their net worth plummet while their debt load remains stubbornly elevated.

Americans saw wealth plummet 40 percent from 2007 to 2010, Federal Reserve says. (Source)

This chart is nominal rather than real (adjusted), but the relative expansion of debt is clearly visible:

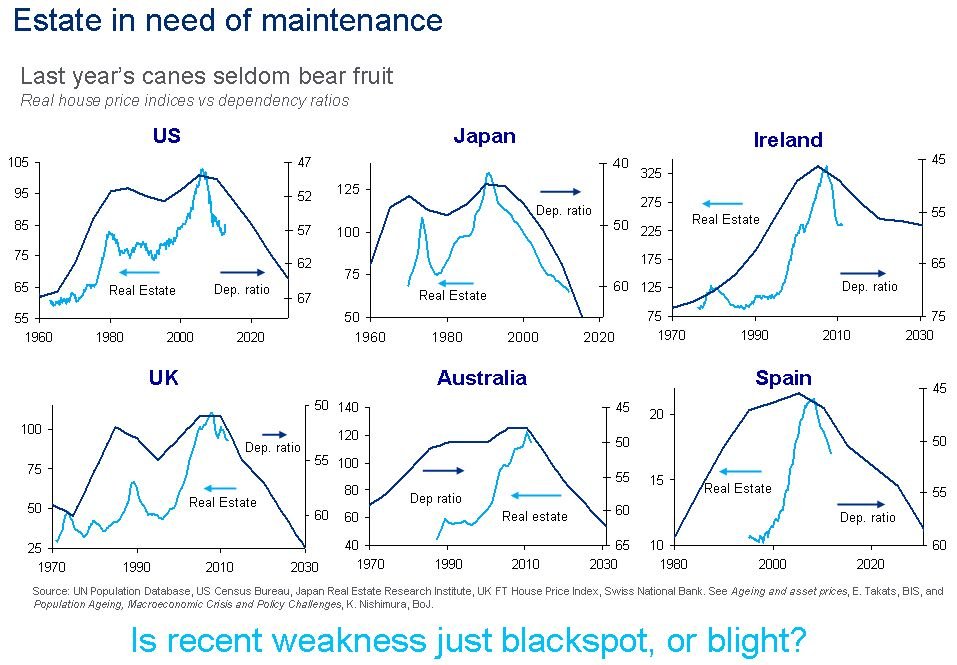

Citi’s Global Head of Credit Strategy, Matt King, Dependency Ration

The slide from Business Insider

An academic must-read is Amir Sufi’s “Will Housing Save the U.S. Economy“.

1 comments

Sergej

2013-03-09 at 13:27 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

Very interesting data. Thank you for the compilation!