In this chapter we connect three related concepts: inflation, central banks and interest rates.

Inflation

As a nation’s economy strengthens over time, prices tend to rise as consumers are able to spend more of their income. The more we make, the better our vacations can be, and the greater amount of goods and services we are able to consume. The rise in prices is called inflation. As long as inflation rises and interest rates are low, the best idea for investors is to buy stocks or real estate. These asset classes typically rise together with inflation.

This creates a loop where more money chases roughly the same amount of goods which can lead to higher prices for those goods. If inflation is allowed to run rampant, our money will lose much of its buying power, and ordinary items such as a loaf of bread may one day rise to unbelievably high prices, such as a hundred dollars per loaf, the so-called “hyper-inflation“. In the 1970s higher inflation led to a loop.

The break-up of the Bretton Woods system and a strong rise in oil price led to the rational expectation among unions and works was built up that inflation will increase every year (e.g. from 8% in 1975 to 10% in 1976 and 12% in 1978). Therefore workers increased their demands even higher and additionally fueled it with wage inflation. More and more people were unemployed and nominal GDP growth was slower than inflation. The combination of inflation and a contracting economy is called stagflation.

To stop the dangers of stagflation and hyperinflation before they emerge the central bank steps in and raises interest rates in order to stem inflationary pressures before they get out of control.

Higher interest rates make borrowed money more expensive, which in turn dissuades consumers from buying new homes, using credit cards and taking on any additional debts. More expensive money also discourages corporations from expansion, as so much business is done on credit, from which interest is always charged.

Eventually, higher rates will take their toll as economies slow down and stock prices begin to fall, until a point where the central bank will begin to lower interest rates. This time, the reduction in rates is to encourage economic growth and expansion. The central bank has to perform a delicate balancing act of trying to foster growth while at the same time keeping inflation low.

(This section was based on a DailyFX article, with some additions and corrections.)

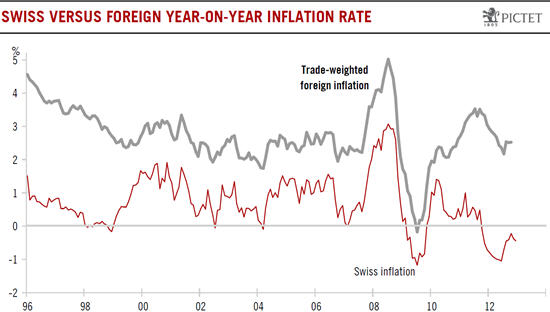

The following is the inflation difference between Switzerland and its trading partners (most recently 40% euro zone, 20% U.S. and 30% emerging markets, 10% others like Japan, UK).

In this chapter we connect three related concepts: inflation, central banks and interest rates. - Click to enlarge

Interest Rates and Central Banks

Central banks set the basis for all interest rates set by banks for borrowers and lenders. The US Federal Reserve calls this basis rate the “Federal Funds Rate“. It is the yearly rate with which US banks lend and borrow money over-night among each other. The effective Federal Funds Rate may be slightly different from the target Federal Funds Rate, which is the rate the Fed communicated. To fine-tune this difference the Fed is able to do Open Market Operations, during which the Fed buys and sells government bonds.

Other central banks use other key rates. These can be:

- The repurchase agreement rate (repo rate) or the rate for the main refinancing operation (MRO), as the ECB calls it. It is the rate at which commercial banks can obtain liquidity from the central bank against a collateral (usually a government bond that is later repurchased by the bank). The time-frame of this type of loan is usually longer than a week.

- The discount rate (or lending rate) is the yearly rate at which financial institutions borrow from the central bank overnight. Typically the banks use promissory notes as collateral. The Bank of Japan still uses the discount rate as the key rate. It is called the “discount rate”, because the banks obtain the funds only with a discount and pay back the whole amount. The interest rate calculated from the difference of the two amounts constitutes the discount rate.

- The sight deposit rate is the yearly rate at which the central bank remunerates financial institutions if they deposit money. The Norges Bank uses this rate as the key rate, currently at 1.5%. It additionally indicates the D-Loan rate, the equivalent of the discount rate; recently it has been 1% higher than the sight deposit rate. The ECB also indicates the sight deposit rate, which is typically 75 basis points lower than the MRO rate.

- The Swedish Riksbank specifies all three: discount/lending rate, sight deposit rate, repo rate.

| Date | Riksbank key interest rates | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Deposit rate | Lending rate | Repo rate | |

| 25/03/2013 | 0,25 | 1,75 | 1,00 |

| 26/03/2013 | 0,25 | 1,75 | 1,00 |

| 27/03/2013 | 0,25 | 1,75 | 1,00 |

- The London Interbank Offered (Libor) rate is the yearly rate at which London banks borrow and lend money overnight for the concerned currency. The Swiss National Bank (SNB) mostly uses the Libor rate as target. The Federal Funds Rate is the equivalent for the US, the Cash Rate (or interbank overnight rate) the equivalent for the Royal Bank of Australia (RBA). The banks’ lending/offer rates are – except in periods of high financial stress – higher than the central bank deposit rates, but lower than the lending rates.

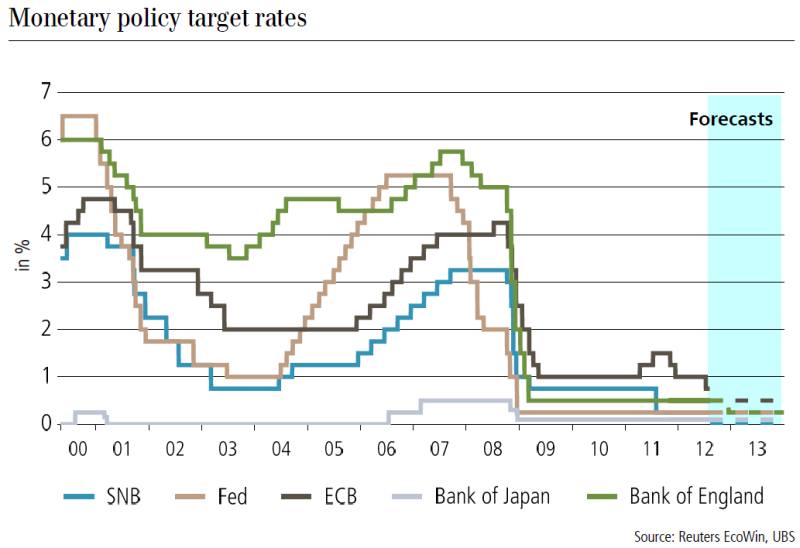

The following graph shows interest rates of different central banks over the last years:

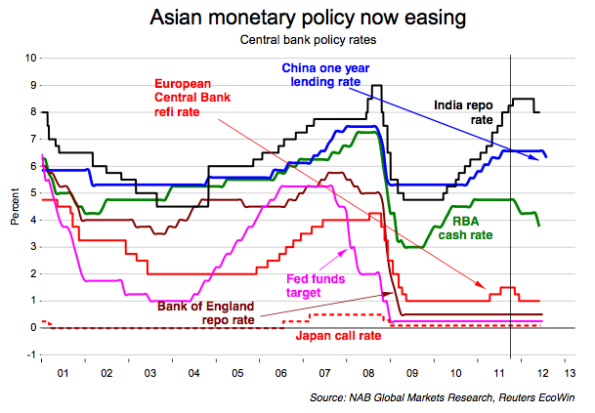

The following are the rates in Asia compared to the BoE and Fed:

See more for