The balance of payments model states that a currency is valued based on balance of payments. The currency of a country with a positive balance of payments, must appreciate. The balance of payments is the sum of the balances of current account and capital account.

The balance of payments leads to many confusions because definitions vary. Essentially the balance of payments do not reflect payments, i.e. accounting entries. But it is a flow model, similar as cash flow analysis for companies.

For example, the IMF’s definition is different from the usual or historical definition. Secondly, the relationship between the balance of payments and reserve assets is difficult to grasp, especially in the IMF definition. Thirdly the origin of “errors and omissions” is often unclear. Therefore we give an explanation in around 400 words, that clarifies the relationships.

Balance of Payments (BOP)

The balance of payments (BoP) consist of three main parts or “accounts”:

- The current account

- The second category is the capital account, as called traditionally, or “financial account” according to the IMF and central banks.

- The IMF treats capital transfers as a third category called “capital account”. This relatively small and unimportant account “capital transfers”,1 applies e.g. when governments forgive debt or when migrants move country. For total confusion this account is often called “capital account” (e.g. ECB). Finally the IMF1 unites the big financial account with the small capital transfer account to the “capital and financial account”.

Subaccounts of the Balance of Payments (source)

Sub-Accounts of the BOP

The balance of payments contains different (sub-) accounts. For each account the balance between inflows and outflows is measured. One example is the trade balance for goods. The balance is the value of the inflows during the period considered, for example, money received for goods sold minus money paid for goods purchased in the year 2012.

Sub-accounts of the current account

The main sub-accounts of the current account are accounts such as

- the trade balance for goods

- the trade balance for services

- primary income account: income from investments abroad

- secondary income account: payments to workers that commute from one country to another

- transfer payments from people living abroad to their families

Sub-accounts of the capital account

The main components of the capital account (or “broadly defined capital account” as Wikipedia calls it) are

- the direct investments account

- the portfolio investments account: As visible in the graph above, it contains

- the lending accounts of and the bank, corporate, government and central bank – officially called “other investments”.

Reserve assets, assets bought by the central bank, are also included in the “broadly defined capital account”, while in the narrow definition it is excluded.

Important equalities

The sum of the current account and the capital account movements is zero except for some errors and omissions:

We prefer to use a capital account that is a “narrowly defined capital account” that excludes reserve assets from the capital account. This leads to the following equations:

Since some data, especially in the capital account is difficult to obtain, some errors and omissions arise. The change in reserve assets is easy to obtain via the central bank. Therefore the errors and omissions are parts of the “corrected BOP Balance”, the final Balance of Payments.

or replacing corrected BOP with BOP:

When a country has BOP surpluses then its reserve assets increase.

Wrong definition of the BoP Model in Wikipedia

The following definition of the Balance of Payments model found in Wikipedia as of April 19, 2014. Since this definition only considers the current account but not the capital account, it is wrong. It reflects the rather the accounting or payment view, but the above cash flow view. That in the long-run the accounting view will finally determine the cash flow view, is a different question.

While the BoP model states that a currency appreciates, when BoP augments. Wikipedia concentrates on the positive current accounts.

Balance of Payments Model

The balance of payments model states that a currency is valued based of the balance of payments. The currency of a country with a positive BOP balance (a BOP surplus) must appreciate; while, one with a BOP deficit must devalue over time. The reason, in the case of a local BOP surplus, the local currency is therefore a relatively scarce good.

The equivalent in BOP terms, is that the currency appreciates when the BOP is positive, namely when

- either the current account surplus is higher than outflows in the capital accounts, in short: Current Account > Capital Account

- or that inflows in the capital account are higher than current account deficits (also called “carry trade”), in short: Capital Account > Current Account

The German Mark between 1980 and 1999, the Swiss franc from 1970 to 2005 are examples for the first case: Current account surpluses that are higher than capital account outflows.

Brazil or India are examples for the second case between 2009 and 2011 when their currencies appreciated (in nominal terms). For many developing economies carry trade phases ended with a currency collapse, like in case of Brazil or India in 2013.

The Japanese yen from 1961 to 1990, the German Mark from 1952 to 1981, the Swiss franc from 2008 to 2012 and since 2001 the Chinese Yuan, the Swedish, the Czech Krona and partially the euro zone are examples were both current and capital account were positive during many years. Consequently the currencies appreciated very strongly.

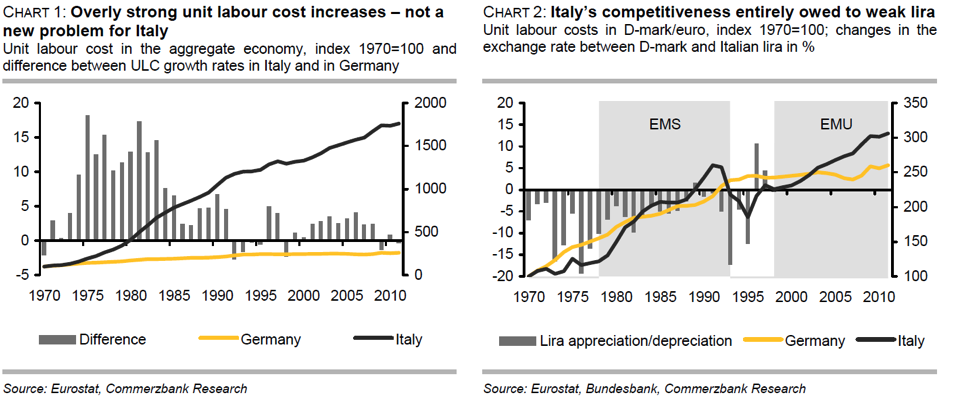

Equivalently a currency depreciates when the current account deficit cannot be covered by capital inflows. Some countries were regularly forced to devalue their currency, which helps to make the country more competitive. One example was Italy.

The idea of the euro is exactly to disallow such continuous devaluations of the currency, therefore some people (like we) think that the euro is similar gold standard because since a couple of years it is controlled by the “inflation-hater” Germany.

Applications

In the following we look on the accounts of the balance of payments. Be ware that the following are the changes to the

A country which has a current account surpluses is able to accumulate a positive net international investment position over the years. Therefore it has foreign assets that it might sell in case of a crisis to honour creditors. The country’s company’s foreign assets can absorb the crisis effects and satisfy creditor demands. In times of risk averseness, Swiss or Japanese companies repatriate foreign gains into local currency and push the yen or franc upwards. Long-term investors follow this example. Despite the strong franc the Swiss account surplus is still on the rise. During the carry trade era, however, many Swiss companies left foreign incomes in foreign currencies.

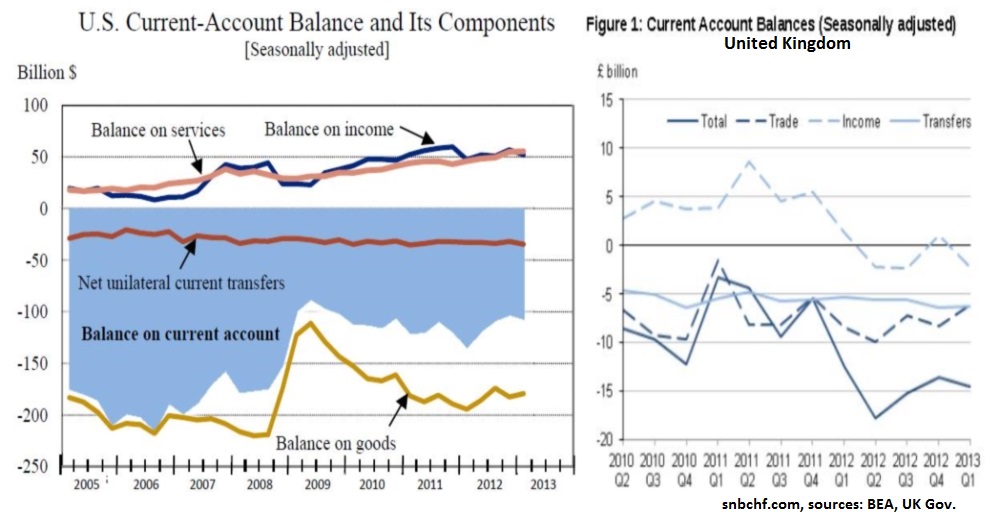

The current accounts of the United States and the UK are mostly negative, while China, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the oil-exporting nations have often so-called “structural current account surpluses”. Read more for long-term currency movements based on current account balances.

Capital Account (or Financial account)

Capital accounts contain the following:

- Foreign direct investment (FDI), refers to long term capital investments, such as the purchase or construction of machinery, buildings or even whole manufacturing plants. If foreigners are investing in a country, that is an inbound flow and counts as a surplus item in the capital account. If a nation’s citizens are investing in foreign countries, that is an outbound flow that will count as a deficit. After the initial investment, any yearly profits not re-invested will flow in the opposite direction, but will be recorded in the current account rather than as capital.

- Portfolio investment refers to the purchase of shares and bonds. As with FDI, the income derived from these assets is recorded in the current account; the capital account entry will just be for any international buying or selling of the portfolio assets.

- Other investments include capital flows into bank accounts or provided as loans. Large short term flows between accounts in different nations are commonly seen when the market is able to take advantage of fluctuations in interest rates and / or the exchange rate between currencies. Sometimes this category can include the reserve account.

- Derivatives: contain the activities of FX traders and purchases of options, forwards and swaps that reflect future expectations of exchange rates or investments concerning the country

- Reserve Account.

The reserve account is operated by a nation’s central bank to buy and sell foreign currencies; it can be a source of large capital flows to counteract those originating from the market. Inbound capital flows (from sales of the account’s foreign currency), especially when combined with a current account surplus, can cause a rise in value (appreciation) of a nation’s currency, while outbound flows can cause a fall in value (depreciation). If a government (or, if authorized to operate independently in this area, the central bank itself) doesn’t consider the market-driven change to its currency value to be in the nation’s best interests, it can intervene. (source Wikipedia).

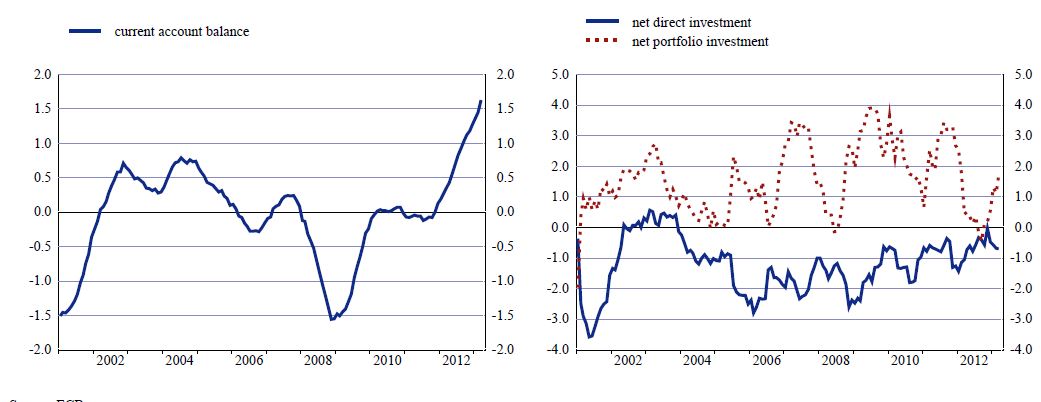

A big part of portfolio investments are money market movements that move with higher or lower interest rates into this or that country. Foreign Direct Investments tend to show more stable tendencies, emerging/developing economies have rather inflows while advanced economies see more outflows.

Like most developing nations, China has rather FDI inflows (source FT)

Apart from FX traders, portfolio investments are the component that cause a strong volatility in foreign exchange rates. With the European crisis there was a big outflow of portfolio investments from Europe that helped to push the euro down from 1.32 to 1.23 in June 2012.

Thanks to the cheap euro, the euro zone current account was strongly positive. But it was not sufficiently high to cover the outflows in the capital account, especially in portfolio investments.

The European Central Bank delivers the balance of payments monthly.

Balance of Payments Eurozone 1999- 2013 (source ECB)

Between January and August 2011, the situation was completely different, based on cheap money from QE2, euro zone interest rates rose and portfolio investments moved into China and the euro zone.

The second part:

The History of the Swiss Balance of Payments

- International Monetary Fund: Balance of Payments Manual, page xi, online link [↩] [↩]