The desire to improve our social standing is natural. What’s unnatural is the toxicity of doing so through social media.

It seems self-evident that the divisiveness that characterizes this juncture of American history is manifesting profound social and economic disorders that have little to do with politics. In this context, social media isn’t the source of the fire, it’s more like the gasoline that’s being tossed on top of the dry timber.

My thinking on social media’s toxic nature has been heavily influenced by long conversations with my friend GFB, who persuaded me that my initial dismissal of Facebook’s influence was misplaced.

Our views of all media, traditional, alternative and social, is of course heavily influenced by our own participation / consumption of each type of media.Those who watch very little corporate-media broadcast “news” find the entire phenomenon very bizarre and easily mocked, and the same holds true for those who do not have any social media accounts: the whole phenomenon seems bizarre and easy to mock.

As for alternative media, many people accustomed to traditional media have never visited a single blog or listened to a single podcast.

Part of my job, as it were, is to monitor all three basic flavors of mass media, and do so as objectively as I can, which is to say, seek out representative narratives and commentaries across the full political and social spectra of each media.

So why is social media so toxic to healthy dialog and tolerance, and to those who live much of their lives via social media? I think we can discern several dynamics that direct the entire social media space.

1. The feedback loops within each “tribe” strengthen the most divisive, toxic narratives and opinions.

In the anti-Trump tribe, for example, those calling most vociferously for Trump’s head on a stake are “rewarded” by praise from other members of the tribe via “likes” and positive comments on the “bravery” of their extreme language.

Others note this feedback and are naturally drawn into trying to top the extreme language: I want Trump’s head on a stake, and then let’s set it on fire, etc.

In the real world, expressing such extreme views soon draws negative or moderating feedback from those outside the social media’s claustrophobic “tribe.” More reasonable people will politely suggest that such extremism isn’t very helpful, or they will start shunning the frothing-at-the-mouth firebrand.

But in the social media world, there are no moderating feedbacks. Anyone who dares question the extremism being reinforced by the “tribe” is quickly attacked or ejected from the tribe. Attacking moderate voices increases the potential “rewards” / likes from tribal members.

2. All human social interactions have a potential impact on the perceived relative status level of the participants, and jockeying for higher status is embedded in social animals such as humans. So naturally we’re drawn to organizing our participation in social media around the implicit task of improving our status / upward mobility.

In the real world, it’s relatively arduous to increase one’s social status,especially as the widening wealth/income gap effectively disenfranchises an increasing percentage of the populace.

In the real world, increasing one’s social status depends on one’s class, i.e. who we hope to impress. Raising one’s status usually requires some expenditure: a trip abroad to an exotic locale that few other social climbers have visited; a new fully loaded pickup truck, another graduate degree, a trip to Las Vegas, etc.

In the social media world, increasing one’s perceived place in the pecking order of “likes” (or views), number of “friends”, etc., depends less on conspicuous consumption / bragging (without appearing to brag, of course) and more on pleasing the tribe in ways that garner more “likes” and “friends.”

In the real world, to raise one’s status, we need to flash the diamond ring, show off the new luxury car/truck, flash photos of the exotic locale, display the graduate diploma, etc. But online, there’s very little in the way of verification: we are who we present ourselves to be.

As opportunities to upward social/financial mobility fade and downward mobility becomes the norm for a great many individuals and “tribes,” the appeal of a cost-free way to increase one’s status increases proportionately.

3. The expansion of the number of “tribes” one can belong to in social media. In the real world, jockeying for higher status is limited to one’s immediate circle of family, friends and colleagues, and to a lesser degree, wider circles in membership organizations such as alumni groups, trade associations, etc. It’s hard to impress the wider world because very few of us have any access or exposure in traditional media.

But in social media, we can become “known” and “liked” in Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, etc. or within specific online communities within the social media world. In other words, if we can’t “be somebody” in the wider world or the real world, we can still “become somebody” in a smaller (but still very real and important to its participants) group online.

| The desire to improve our social standing is natural. What’s unnatural is the toxicity of doing so through social media.If we put these three dynamics together, it’s little wonder so many people are drawn to living a major part of their lives online, and modifying their behaviors and views to increase their social standing / visibility online by whatever attracts more view, “likes” and “friends.”

These dynamics help us understand why social media is intrinsically toxic to civil society: being civil doesn’t raise one’s status, while reaching for new extremes is rewarded by the “likes” and “friends” all humans crave as manifestations of our social status. |

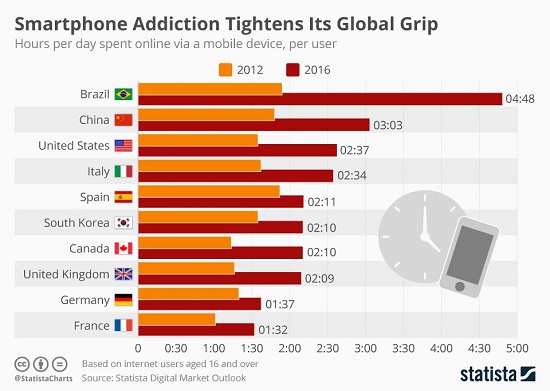

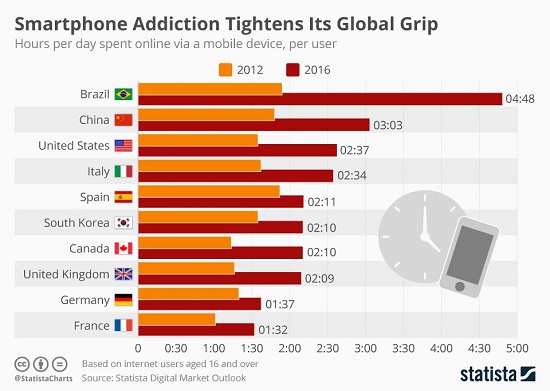

Smartphone Addiction Tightens Its Global Grip - Click to enlarge |

Full story here

Are you the author?

At readers' request, I've prepared a biography. I am not confident this is the right length or has the desired information; the whole project veers uncomfortably close to PR. On the other hand, who wants to read a boring bio? I am reminded of the "Peanuts" comic character Lucy, who once issued this terse biographical summary: "A man was born, he lived, he died." All undoubtedly true, but somewhat lacking in narrative.

Previous post

See more for 5.) Charles Hugh Smith

Next post

Tags:

newsletter