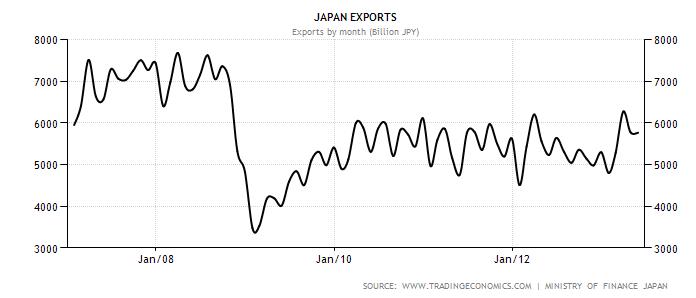

Exports and imports typically fluctuate with a rising or falling currency. When a currency appreciates then exports and imports fall when calculated in the local currency, and with a weaker currency exports and imports increase. The typical picture is shown in the Japanese exports.

With the weak dollar after the financial crisis the yen strongly appreciated and Japanese exports plunged. When the yen fell in winter 2012 (and also winter 2011) Japanese exports recovered a bit on a yen basis.

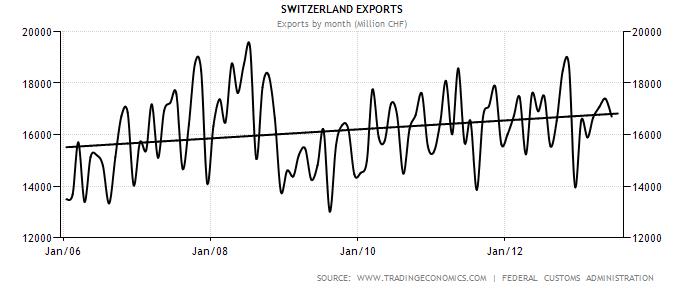

The picture for Switzerland is different: the stronger franc could not prevent higher exports.

We explain the rising exports with the structural strength (e.g. low taxes, efficient administration and high savings rate) of the Swiss economy and the highly-qualified personnel that migrated into Switzerland after the Swiss-EU bilateral agreements and who are still coming from the weak countries of the euro zone.

On the other side, the Japanese have falling savings rates, low immigration, high public debt and spending and in particular a negative trade balance.

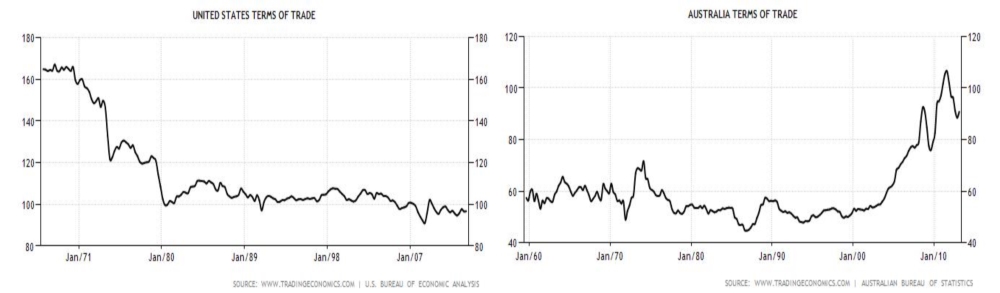

Terms of trade

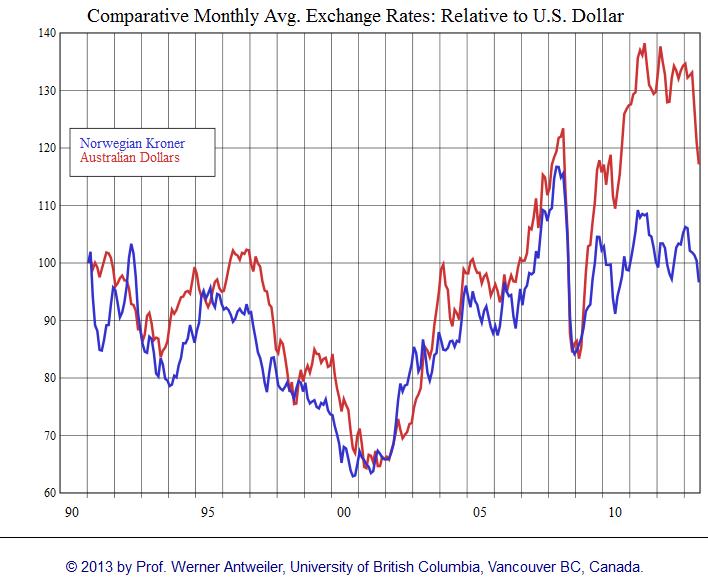

Terms of trade typically increase when export prices increase more than import prices. A standard example is Australia, where exported goods like copper and other commodities heavily lifted the terms of trade in the last decade. In the U.S. things were different: high import costs of oil weakened the U.S. terms of trade.

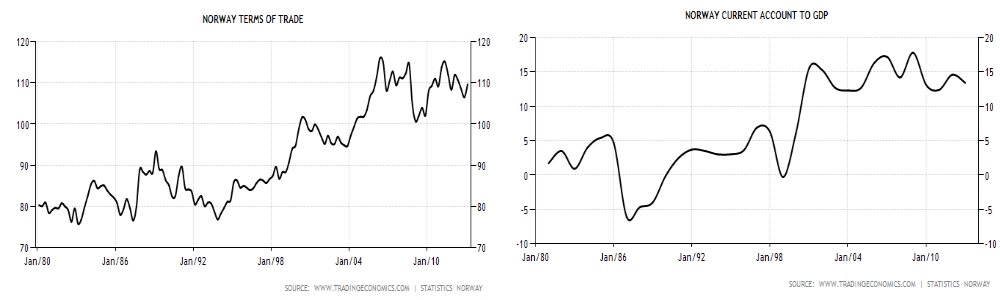

The typical result of weakening terms of trades over the tong-term is a weaker trade balance; stronger terms of trade lead to better trade balances and current accounts. While we all know about the negative US trade balance, Norway exhibits a positive effect:

Over the long-term, stronger trade balances translate into a stronger currency , in our example the clear winner is the Norwegian Kroner.

Price-adjusted (real) trade balances

Similar to the terms of trade, trade balances may be adjusted for price changes. Based on today’s Swiss trade data we created a spreadsheet that contains export and import price changes for each half-year (H1 and H2).

data source Swiss Customs, e.g. here latest report

The table shows that a quickly strengthening currency may weaken the terms of trade and consequently the trade balance.

For example, between the second half of 2010 and the first half of 2011, the EUR/CHF fell from an average rate of 1.35 to a 1.25 (the dollar lost even more). Consequently, Swiss export prices fell by 6% y/y in H1/2011, while import prices only receded by 1.9%. Terms of trade were weakened. In H1/2009, however, Swiss export prices increased by 2.1% y/y while import prices fell by 5.9% (mainly due to cheap energy prices). Terms of trade strongly improved.

Since the first half of 2012 and with the CHF cap introduction, we see the strengthening of Swiss terms of trade again: in Q2/2012 the prices of exports rose by 3.9% but imports only by 3.2%. In H1/2013 there was the same picture: export prices were up 3.4% and import prices only by 2.4%. Source of the data Swiss customs, e.g. the latest report.

Similarly, we can calculate a simple price-adjusted (i.e. real) trade balances. A simple adjustment for prices shows that especially in H1/2011 the real trade balance fell by 33.2% against the previous year. On the other side, the real trade balance was particularly good in 2009 thanks to falling energy prices and a still weak franc. Due to the SNB intervention, the real trade balance strongly recovered by 65% y/y in H1/2012.

The economic reason behind is that the replacement of manual work with capital and innovation takes some time. Central banks try to prevent the excessively quick changes of terms of trade with currency interventions, so that no jobs are lost. The current account surplus and the stronger terms of trade show that the cap on CHF might not have a reason to exist in 2013.

Effectively the trough in 2010/2011 in the real trade balance above coincides with the drop in the Swiss current account to GDP ratio from 14% of GDP to 9% in 2011. But thanks to the cap on CHF, the surplus has risen to 14% of GDP again.

History shows that currencies with trade and current account surpluses appreciate over the long-term. The logical reason behind is that foreigners must buy this currency while the surplus country sells the goods and services.

And in this case one thing seems to be clear:

in the long-term the Swiss franc must appreciate.

Read also:

Forthcoming: Understand the current account and why the Australian dollar did not appreciate against the US dollar between 1990 and 2013 despite the commodity boom and why it should continue falling.

See more for