Disregard these second-order effects at your own peril.

A great many systems that are assumed to be robust are actually fragile. Exhibit #1 is the global financial system, of course, but Exhibit #2 may well be the healthcare system globally and in the U.S.

Observers have noted that the number of available beds in U.S. hospitals is modest compared to the potential demands of a pandemic, and others have wondered who will pay the astronomical bills that will be presented to those who are treated for severe cases of Covid-19, as the U.S. system routinely generates bills of $100,000 and up for a few days in a hospital. Costs of $250,000 or more per patient for weeks of intensive care treating Covid-19 cannot be dismissed as “impossible.”

Beyond the possibility that the logistics and costs of care will overwhelm the system, there are numerous and highly consequential second-order effects to consider. As you may recall from recent posts here: first order, every action has a consequence. Second order, every consequence has its own consequence.

Second-order effects of the pandemic colliding with America’s dysfunctional healthcare system include:

1. People avoiding care because they can’t afford it. Academic studies have shown that high deductibles make patients reluctant to seek care, even when they need it.

This second-order effect will exacerbate the contagion and endanger those suffering from severe symptoms.

2. Potential shortages of medications due to an over-reliance on supply chains in China. The number of unknowns far exceeds the number of knowns in this situation, so complacent assumptions may be misplaced.

3. U.S. healthcare’s obsession with maximizing profits by any means available has transformed healthcare from a calling to just another burnout job in the Corporate America profit-maximizing grinder. A long time general practitioner (physician) recently explained the consequences of this transformation should the pandemic engulf the U.S.:

“The risk of wholesale healthcare system failure from a stress even a fraction of what is experienced in China is deeply, deeply under appreciated.

The transition of medicine from calling to career is nearly complete– as is the removal of any mentors who might teach otherwise.

If Corona hit my community 20 years ago, at a time where all the administrators and most of the staff of our 200 bed hospital lived in town, my partners and would’ve sucked it up and did our best, even at the risk of our life. I’m not boasting or saying we’re heroes, it’s just that that was the way we were trained. White coats were only for the broadest shoulders. And you were taught that the risks of taking care of sick people was part of the deal.

Our patients were our neighbors. They counted on us. Such respect as we were given was due to the fact that we were their healthcare resource.

The leadership and medical staff of the hospital would have done what we could to make it work. And yet here were a number of independent pharmacies and health supplies we could rely on if things got tough.

Then a combination of secondary effects and political influence purchased by deep pocketed competitors put most of the independent clinicians in an untenable place and all left or were absorbed.

Today, though the same organization owns the hospital, none of the management lives in town. Like most health systems, the owners are more is more interested in data collection and foot traffic than healthcare–and it shows. The inpatient doctors are all hospitalists who live far out of town.

| All the other docs in town now work for the same organization, but they haven’t been welcome in the hospital for years. Few of the nursing staff live nearby.

If a real pandemic hits, that hospital will well and truly fail–there’s no other word for it. Docs and nurses won’t show up. It’s not their friends or family or kid’s teacher or pastor at risk. While we wouldn’t have liked it, we would’ve risked our health for our community. These professionals are not going to risk their life for a job. The senior management will try to keep it together for the sake of their careers, but the next tier will quickly bag it. Again, it’s just a job. The corporate supply chain is so fragile and there are now so few community resources that the hospital as a care system will quickly break down. As you have discussed, just because a thing is difficult to measure doesn’t mean it’s not important. The engagement of my partners and I with our community hospital was a critical loss–and that loss of ‘robustness’ won’t be fully understood until the system is stressed. In my community at least, it won’t take much stress for the rot to be revealed.” Disregard these second-order effects at your own peril. Just as unsustainable speculative bubbles burst, unsustainable systems break down once systemic stresses rise above very low levels. |

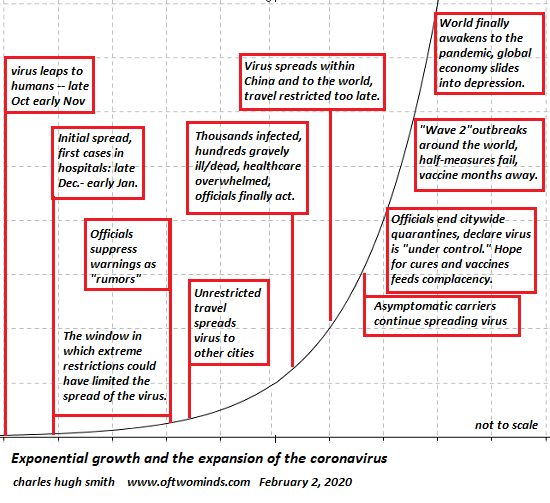

Еxponential growth and the expansion of the coronavirus |

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: newsletter