If we look at these charts, it looks like only the top 10%, or perhaps the top 20% at best, might qualify as “middle class” by the metrics described below.

The conventional definition of working class is based on income and education:the working class household earns between $30,000 and $69,000 annually, and the highest education credential in the household is a two-year community college degree or trade certification.

The definition of the middle class is also based on on income and education, but adds financial security as a metric: the middle class household earns $80,000 or more, holds 4-year college diplomas or graduate degrees, owns a home, has a 401K retirement account and so on.

(My own definition is much more rigorous, as I reckon “middle class” today should have the same basic assets as the “middle class” held 40 years ago:

What Does It Take To Be Middle Class? (December 5, 2013.)

But in some key ways, income and education are misleading metrics: the key attributes that actually define the working class are:

1. Stagnant incomes: incomes that over time barely keep up with real-world inflation or even lose purchasing power.

2. Income insecurity: wages, benefits and pensions are not as guaranteed as advertised.

3. Not enough ownership of financial capital to be meaningful. Financial capital excludes household items, vehicles, etc. Financial capital includes stocks, bonds, certificates of deposit, ownership of a profitable business, equity in real estate, precious metals, bitcoin, etc.

By meaningful I mean enough to:

— augment Social Security benefits in a way that greatly improves the household’s lifestyle and retirement options

— equity that is significant enough to fund college educations so one’s children do not have to become debt-serfs to attend college

— enough capital to fund (or help with) a down payment for a house, i.e. inheritable wealth that transforms the children’s lives while the parents are still alive

— income from capital, i.e. income isn’t dependent on a government agency or government transfer.

How many U.S. households qualify to be middle class if that means:

— the household income has outpaced real-world inflation over the past 20 years

— the household’s financial capital/assets have grown to become meaningful (as defined above) in the past 20 years

— the household doesn’t depend on government transfers for much of its income / spending

— the household income and wealth are not dependent on financial bubbles, corporate guarantees, local government pensions on the verge of insolvency, etc.

While tens of millions of households qualify as “middle class” based on college diplomas and income, far fewer qualify when wealth and financial security are the key metrics. Plenty of households earn well in excess of $100,000 annually, but their financial status is as precarious and threadbare as any working class household.

They don’t own enough assets or capital to move the needle, and what they do own is generally dependent on financial bubbles or speculative gambles.

| Feeling like we belong to the “middle class” because we have a college diploma and make a good income offers up a false sense of pride and progress.If we’re realistic about the financial wealth and security of “middle class” households, most qualify as working class: stagnant incomes, precarious financial circumstances, very little meaningful wealth and even less meaningful wealth that isn’t dependent on the bubble du jour or promises that might not be kept. |

Pretex Income Growth in the United States - Click to enlarge |

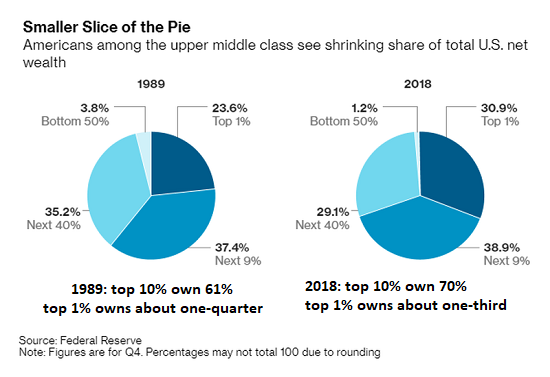

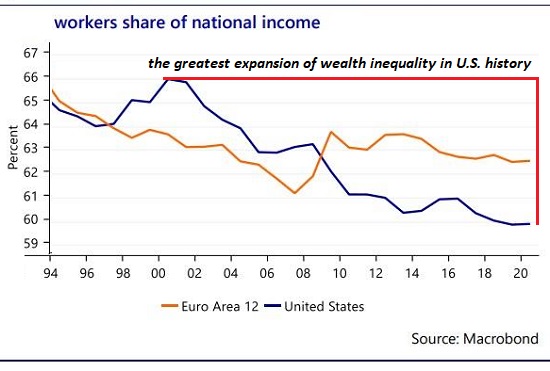

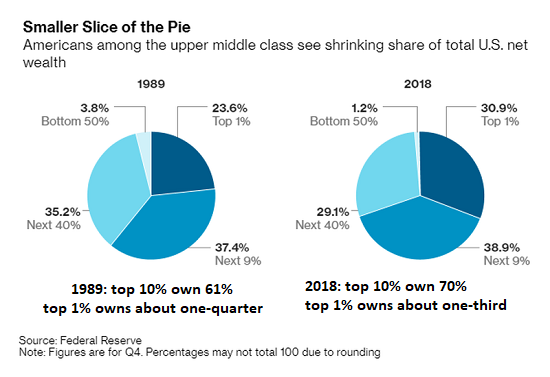

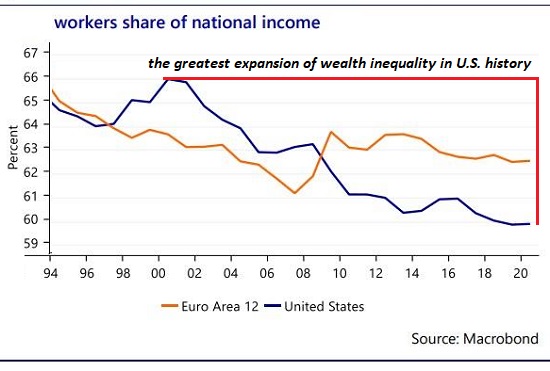

| If we look at these charts, it looks like only the top 10%, or perhaps the top 20% at best, might qualify as “middle class” by the metrics described above. |

Concentration of stock ownership by Wealth Bracket - Click to enlarge |

| What sort of society do we have if the bottom 20% of households are poor, the next 60% are working class/precariat and only the top 20% (at best) have any of the core attributes of “middle class” financial security and wealth? |

Smaller Slice of the Pie, 1989 and 2018 - Click to enlarge |

| If we take off our rose-colored glasses, we have a much more stratified economy and society than we might like to believe: there’s the top 1%, the next 4% “upper middle class,” the next 10% “middle class,” the next 65% working class, and the bottom 20% poor, those largely dependent on government transfers.

The “middle” has eroded away, leaving the top 15% who are doing very well in the status quo and the bottom 85% who are struggling to maintain a meaningful sense of prosperity and progress.

Personally, I’m proud to be working class in terms of my skillsets and values. Labels mean nothing. What counts is having skills, drive, agency, curiosity, frugality, integrity, self-discipline and kindness. Those forms of wealth cannot be taken from you when the bubble du jour pops and all the phantom “wealth” vanishes like mist in Death Valley. |

Worker Share of National Income, 1994-2020 - Click to enlarge |

My new book is The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake. For more, please visit the

book's website.

Full story here

Are you the author?

At readers' request, I've prepared a biography. I am not confident this is the right length or has the desired information; the whole project veers uncomfortably close to PR. On the other hand, who wants to read a boring bio? I am reminded of the "Peanuts" comic character Lucy, who once issued this terse biographical summary: "A man was born, he lived, he died." All undoubtedly true, but somewhat lacking in narrative.

Previous post

See more for 5.) Charles Hugh Smith

Next post

Tags:

newsletter

1 comments

Stefan Wiesendanger

2019-06-17 at 17:14 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

Is the problem for the disappearance of the middle class not behavioral? Of course the lack of savings can be blamed on an economy that does not provide decent wages. It can be blamed on a system of education that does not focus enough on skills that actually have value. It can be blamed on a monetary policy that disproportionately favors the rich, on bailouts, on tax breaks for the rich, on favoritism, etc. All these reasons have elements of truth in them and there are recipes for beginning to correct each one of them.

But finally, it seems to me from a distance that the biggest problem is behavioral. Consumption on credit instead of pre-saving prevents the individual family from building capital. Consumption on credit prevents the Government and the economy as a whole from building capital. And what capital is built is financed and therefore owned by foreign investors. So the remedy has to be behavioral as well:

1. Save before you spend and accept these limitations

2. Prefer investive to consumptive use of funds

At a macro level, one can debate the adequacy of a higher or lower savings rate. There are good arguments both ways: global imbalances in favor of a higher and the “consumer-of-last-resort” argument recommending a lower savings rate. While this is hard to decide at a macro level, it is obivous that the savings rate is at historic and international lows. And it is also clear that borrowed money is spent on things that are not investive but consumptive and therefore should be expensed: the military, credit card debt, student loans (to a large extent), car loans (to a large extent)

It is not a law of nature that a mature economy becomes an old debtor nation, it is a choice. For an individual and for a country as a whole.