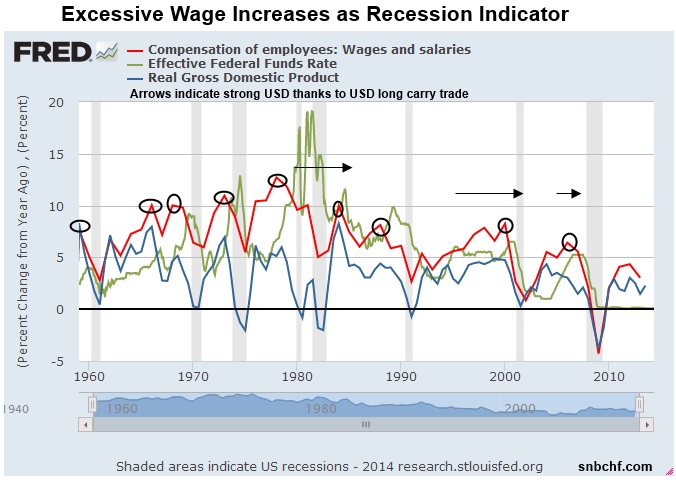

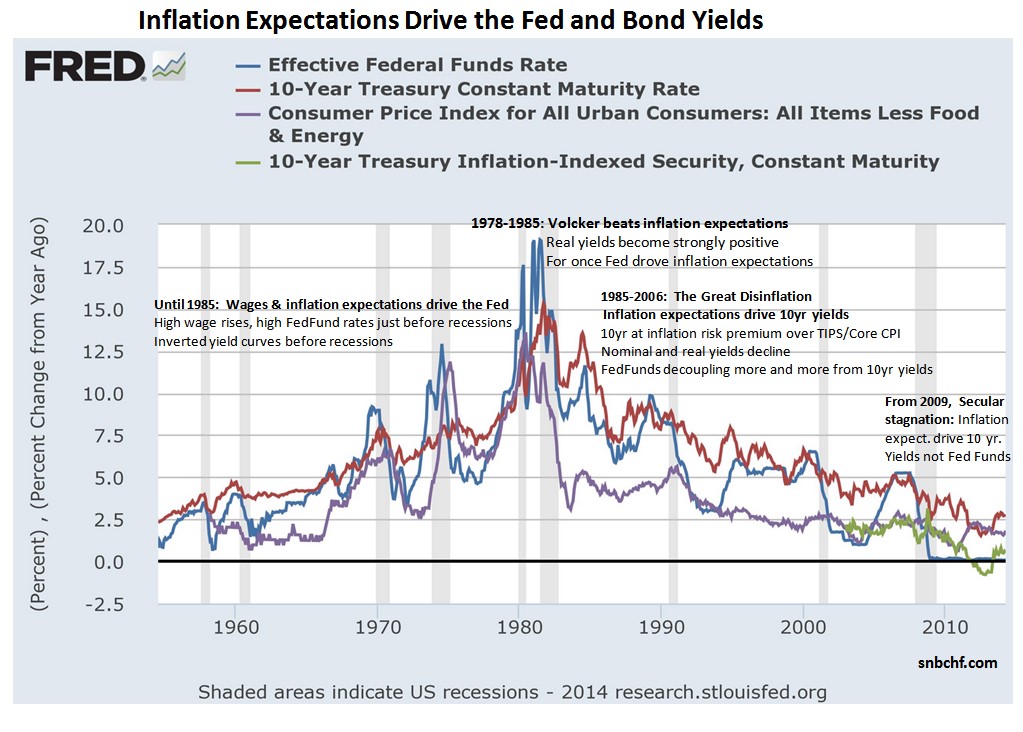

In our little history of wages, inflation, Treasuries and the Fed, we show that inflation and wage expectations drive both the behaviour of the Fed and ten-year bond yields.

Claudio Borio of the Bank for International Settlements and Piti Disyatat of the Bank of Thailand brought the insight of that history post in a nutshell.

Central banks pin down the short end of the yield curve, while financial-market participants price longer-dated yields based on how they expect monetary policy to respond to future inflation and growth, taking associated risks into account. Observed real interest rates are measured by subtracting expected inflation from these nominal rates. source VoxEU

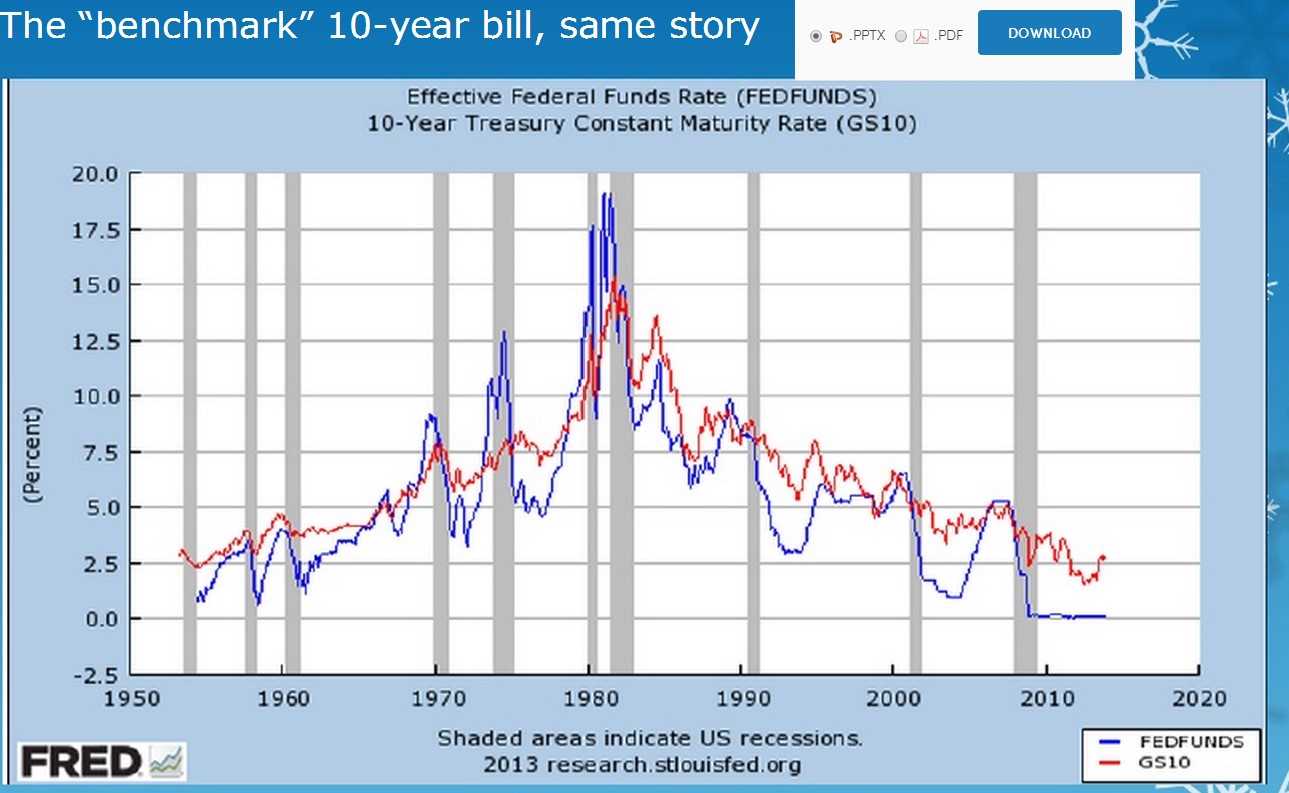

10 year yields decoupled from short-term rates

In former times short-term rates gave an indication of longer-term inflation and nominal bond yields. But since 2004 the Fed Funds rate, the short-term rate, seems to be decoupled from 10 year yields. It moved up and down between 0.25% and 5.5%, but the 10 year yield continued to fall nearly steadily until 2012. We believe the reason for it, is that wealth in emerging markets rapidly increased and therefore the United States is slowly losing its status as the unique global reserve currency.

MMT got it wrong

The decoupling of Fed Funds and 10 year bond yields is completely opposed to the idea that MMT, the “modern monetary theory” proposes, namely that the Fed not only sets short-term rates, but also heavily influences US bond yields with higher maturities.

Not only here got it wrong, MMT hides inflation in their slides. For us, MMT is a pure academical theory and disconnected from markets and daily life.

source MMT slides

Therefore most market participants think GDP growth and subsequently inflation expectations drive bond yields.

But Cleveland Fed researchers reversed the order.

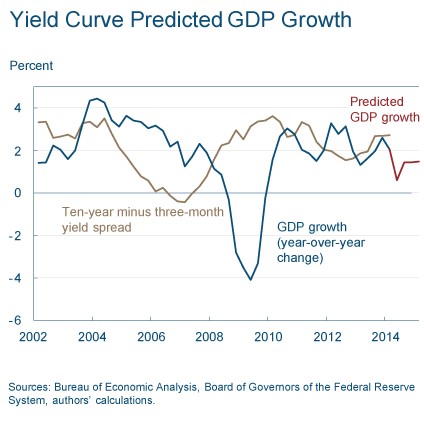

Cleveland Fed researchers Yields determine growth and implicitly inflation expectations

Cleveland Fed researchers argue that the yield curve predicts GDP growth. And since growth creates higher inflation expectations, the chain may reverse.

Moreover, their article gives recession estimates based on the form of the treasury yield curve. Interestingly the Cleveland Fed removes the Fed and the Fed Funds Rates completely from the picture.

The General Relation between bond yields, inflation expectations and GDP growth

We still maintain that:

Step 1: Inflation expectations drive the behaviour of both the market and the Fed.

Step 2: The Fed moves short-term rates targeting the Fed Funds rate. More or less synchronously the market reacts to inflation expectations.

Step 3: Bond yields adjust, often but not always, with an inflation premium against short-term rates.

This would imply that:

In the formula above we use nominal GDP growth to account for high inflation periods. In the graph, the Cleveland Fed takes only the low inflation period since 2002 into account and uses real GDP.

One example could be: 2.5% ten year yields correspond to 2% inflation expectation and 2% real GDP growth (or a bit more nominal growth). For 2.5% real GDP growth, you obtain 2.5% inflation expectation and 3% ten year yields. 1.5% real GDP growth would correspond to 1.5% inflation expectations and 2% ten year yields. When you move upwards to 4% inflation expectations, then the dependency is not so pretty and linear any more, real GDP growth would only be 3%, but bond owners would want a 6% yield now; with rising inflation expectations the inflation risk premium rises.

With rising inflation expectations, the following rules are applied:

- Nominal GDP growth remains more or less in line with inflation expectations.

- Real GDP diminishes as compared to inflation expectations.

- Bond yields rise more rapidly than inflation.

At 5% inflation expectations, real growth would fall to 2.5%, but bond holders want 7% yields, the premium against inflation expectation rises. Looking at Brazil or the other Fragile Five economies today, one will recognize the rules depicted in the NAIRU or the Taylor rule.

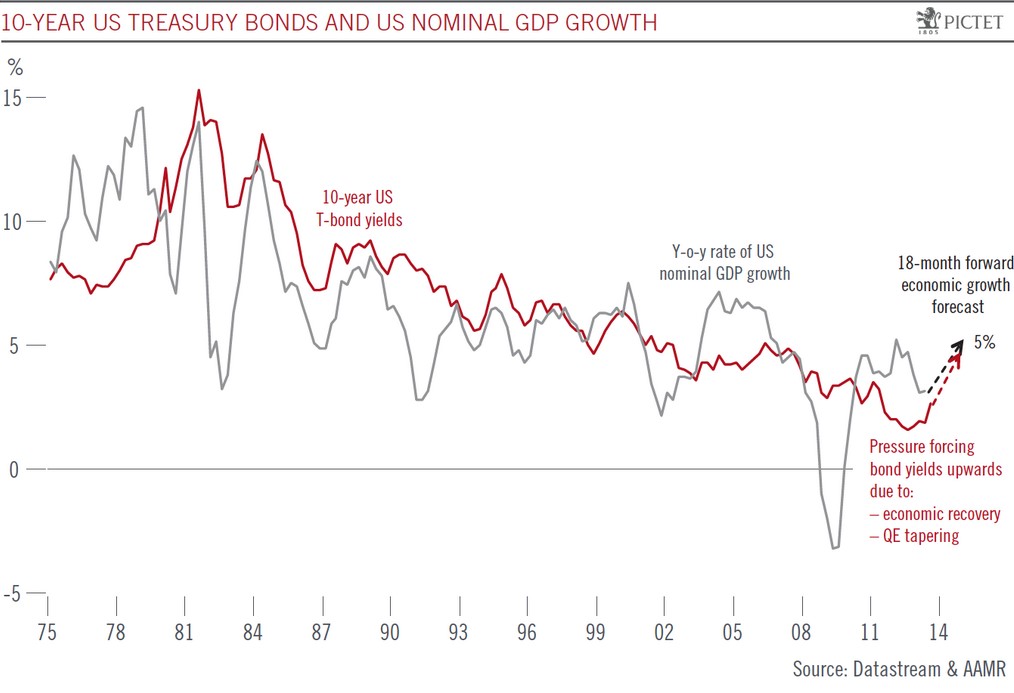

Pictet shows this relationship in a historical picture. If we do not focus on their inability to forecast US growth in 2013, we see how close 10 years Treasury yields track nominal GDP growth.

Pictet shows the close relationship between nominal GDP growth and 10 year Treasuries

What happens if the Fed hikes rates today, would Treasury bonds follow?

If the Fed hikes the Fed Funds rates today, then markets could think that GDP growth expectations, as for the best American economists, have improved. The treasury yield would be copied from its GDP growth expectation friend.

But markets do not always believe the Fed and Fed Funds guidance, in particular in periods of high inflation and high oil prices. In this case an inverted yield curve predicts lower GDP growth. Recently treasury yields have even fallen after Fed member Bullard spoke of higher Fed Funds rates in 2015. The arguments of the market are pretty simply: if the Fed tightens then there is less liquidity and less credit available. Stock markets fall. Less liquidity means for the markets that GDP growth will be lower, because credit growth, our “evil driver” of GDP growth declines. And logically Treasury yields increase.

Market monetarists agree with the Cleveland Fed

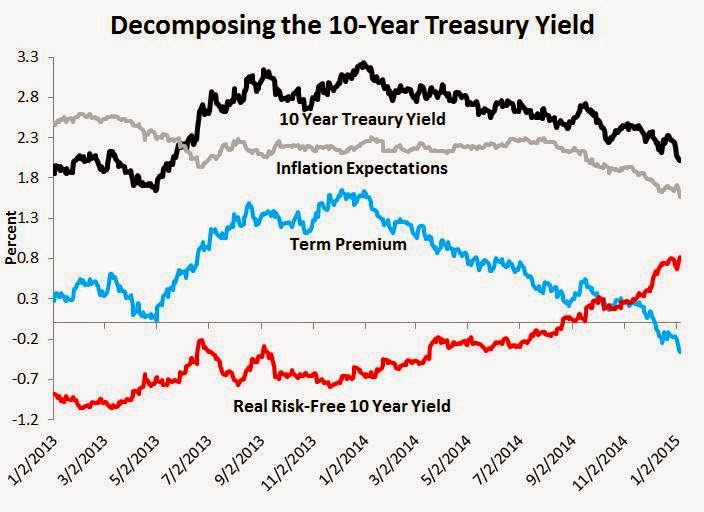

Market monetarists agree with the Cleveland Fed, they think that bond yields and money determine growth. David Beckworth gives more detail on the decomposition of yields into inflation expectations, term premium and real risk-free 10 year yield. He writes:

By looking at these components we can make sense of what is driving the fall in yields. We can also look to the real risk-free interest to see what it implies about the health of the U.S. economy. The Adrian, Crump, and Moench (2013) decomposition of the 10-year treasury yield into these components is below:What we see is that changes in inflation expectations and the term premium are both behind the decline in the 10-year treasury interest rate. This suggest that there may be concerns about future inflation–though this might also be reflect the temporary drop in inflation from declining oil prices–and that there has been a rush into treasuries because of the worries about the Eurozone and China.

But there is more. After being negative for several years, the real risk-free interest rate has been steadily climbing and is now positive. This only happens when the economic outlook improves as seen in the figure below. It shows a close relationship between the real risk-free interest rate and the business cycle:

So the upward trend of the real risk-free rate implies we are in the midst of a solid recovery in the United States. This interpretation is supported by the spate of positive economic news shows. Yes, the economic problems in Europe and China could eventually harm the U. S. economy. But for now the U.S. economy seems to be in the clear.So be careful when interpreting long-term treasury yields. They might be signalling a robust recovery even if they are falling.So the upward trend of the real risk-free rate implies we are in the midst of a solid recovery in the United States. This interpretation is supported by the spate of positive economic news shows. Yes, the economic problems in Europe and China could eventually harm the U. S. economy. But for now the U.S. economy seems to be in the clear. So be careful when interpreting long-term treasury yields. They might be signalling a robust recovery even if they are falling.

Are American companies able to set wages and implicitly inflation expectations?

Inflation expectations are closely related to wages, which are determined by American companies. We recently went one step further and claimed that in our globalized world American companies react to global wage developments. They are able to increase wages only if the global competition does so too. Services are becoming similar as tradable goods more and more globalized.

And as we all know, European leaders do not allow higher wages for the sake of “competiveness” of the periphery, while thanks to weaker currencies, wage excesses are allowed in emerging markets.

But, if not even American companies (as a whole) can influence inflation expectations and treasury yields, how can the Fed? More details in our article why the euro will move to $1.50

Read also:

Cleveland Fed: The Yield Curve and Predicted GDP Growth, June 2014

Chartalism and Modern Monetary Theory, MMT

Hans-Werner Sinn’s critique of Piketty

VoxEU: Low interest rates and secular stagnation: Is debt a missing link?

Of course the Fed can control interest rates. You think the market can move the 3mnth bill to 2% if it really wanted? LOL! Give it a go and see how you get on.

The Fed doesn’t explicitly set the 5yr yield but, similar to the 3mth yield, they could if they wanted to. That would obviously have knock on impacts, though likely less destructive than many would predict.

Regarding inflation, the Fed follow inflation expectations and therefore rates do. You are mixing up the causal agent.

For example, if Yellen hiked rates by 1% next month, then yields would pick up right across the curve — your viewpoint would deny this would happen because inflation expectations had not changed and also because higher rates should dampen your vaunted inflation expectations. I suspect you know though, that you would be wrong – that yields would indeed lift.

MMT has clearly been proven right, it’s quite obvious at this point. Railing against it just reveals ideology rather than critical thought.

Reply

“Railing against it just reveals ideology” –> I updated the article to show that MMT is wrong.

The Fed determines short-term rates. Its influence on longer-term yields happens only because often markets believe that they are serious economists and they are able to predict GDP growth.

And when recently spoke of higher Fed Fund rates, Treasury bonds did exactly the opposite, they fell.

MMT is a pure academical theory and disconnected from markets and daily life.

Reply