One of the first to use the word “euro glut” was Deutsche Bank’s George Saravelos. His idea of the euro glut is that European banks and investors drive the euro down despite the massive European current account surplus and the high European household savings rates of 12% compared to 4% in the US.

Saravelos argues that ECB easing will lead to some of the “largest capital outflows in the history of financial markets”. This would counter the “European savings glut” created by savings and current account surpluses. He says:

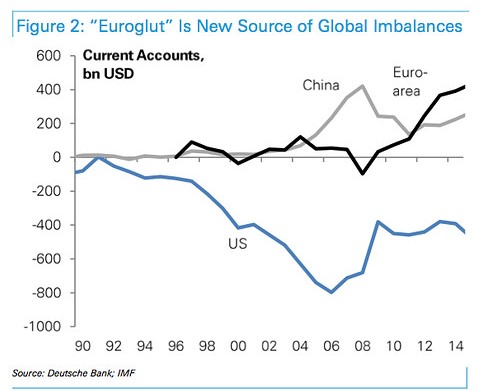

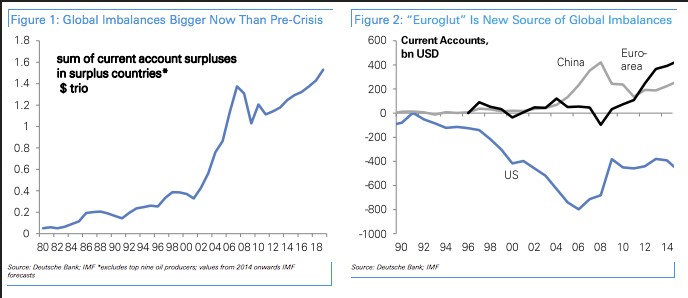

Euroglut is a global imbalances problem. It refers to the lack of European domestic demand caused by the Eurozone crisis. The clearest evidence of Euroglut is Europe’s high unemployment rate combined with a record current account surplus. Both are a reflection of the same problem: an excess of savings over investment opportunities. Euroglut is special for one and only reason: it is very, very big. At around 400bn USD each year, Europe’s current account surplus is bigger than China’s in the 2000s. If sustained, it would be the largest surplus ever generated in the history of global financial markets. This matters.

Euroglut means that as the world’s biggest savers, Europeans will drive international capital flow trends for the rest of this decade. Europe will become the 21st century’s largest capital exporter. This statement is close to an accounting identity – a surplus on the current account implies capital outflows elsewhere.

Our premise is that the next few years will mark the beginning of very large European purchases of foreign assets. The ECB plays a fundamental role here: by pushing down real yields and creating a domestic “asset shortage”, it is incentivizing European reach for yield abroad.

- The outflows will help drive the euro ever lower, eventually dropping below parity with the U.S. dollar. He forecasts the euro to fetch just 95 cents by the end of 2017.

- Yield curves will be very flat, with U.S. fixed income a “primary beneficiary” of European demand. In fact, if there is enough demand for long-dated instruments, the 10-year U.S. yield could easily trade below terminal Fed funds, a phenomenon that occurred in the 2000s amid the so-called bond conundrum and might become more likely now thanks to ever larger current-account surpluses, he says.

- In the long run, this should also be good news for emerging markets as the flows make it more likely that marginal demand for emerging market assets goes up rather than down, he says. (via Marketwatch)

Here an interpretation of FT Alphaville:

Think about policy over the next few years: at least 500bn-1 trillion of excess cash will be sitting in European bank accounts “earning” a negative rate of 20bps. In the meantime, asset-purchases will drive yields down across the board – there will be nothing with yield left to buy.

So, the basic argument here is that while China’s surplus drove Asian policy in the 2000s, the Euroglut will now become the key determining factor driving European policy from now on.

Here are some of Saravelos’ slides:

Saravelos predicts most of the European continent could end up with negative rates or FX managed-regimes.

Europe is the new China, and via large demand for foreign assets, it will play a dominant role in driving global asset price trends for the remainder of this decade

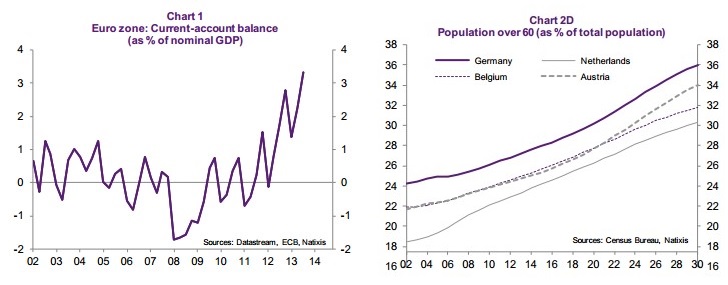

Natixis tracks the increase of the European current account. They also give one reason for the euro glut: The ageing population

For Daniel Eckert and Holger Zschäpitz of the German Welt, the euro glut was the principal reason that the Swiss National Bank gave up the peg to the euro.

We think that the ECB is happy with the euro glut. They are even happy to a certain extend when the Greek crisis further weakens the common currency. A weak euro implies more exports and more jobs in Germany and some export-oriented countries in Southern European, like Italy.

The United States are more increasing the public deficit more than most European states, hence bonds are honored with higher interest rates, 2.5% for ten year treasuries compared to 0.9% for German Bunds or 2.1% yield for Italian and Spanish government bonds (see bond rates). In times of low risk aversion, this hunt for yield translates into an outflow from Europe.

But on the other side, the weak euro may increase inflation, in particular in Germany, where strikes are frequent and labor agreements point to German wage inflation of higher than 3%. Once this wage inflation translates into consumer price inflation, then the ECB must stop her FX-centric policy.

Secondly, a capital outflow needs investible assets:

But when the Fed continues to be reluctant to hike rates and when American wage inflation translates into weaker US company profits, then neither European money market funds nor stock market investors will find the required assets in the United States….. and the euro glut will stop.

I agree with most of the – as usual very original – analysis. If there is one point that deserves further debate, it will be the one that German wage inflation should lead to a cahnge in the ECB’s stance. I think that this alone will not change anything and that it is already discounted in the ECB’s current stance as the desirable policy of Germany. To illustrate my point, let’s start with Dutch labor costs. Through nationally negotiated wage increases, they have gotten ahead of Germany’s by about 20% since the year 2000. What applies to the Netherlands is also true for Belgium and most other Northern European countries, and to a somewhat lesser extent for Sweden and Austria. As a manager of a Dutch firm during that period, I can assure you that the pressure this created when facing our German competitors was similar to what Swiss industry is experiencing. In the Swiss case, the only thing different was the channel through which the effect was felt (exchange rate instead of regulated wages), but the effect was the same: more expensive local input factors.

Source of data: http://www.oecd.org/eco/euroarealabourcosts.htm

Given that considering ULCs, Germany is the odd man out, if the Eurozone is to rebalance internally, German wages had best rise and the ECB not stand in the way. After all, it is the German people who have been deprived of the fruits of their labor in the past decade. The path through higher wages is therefore more sensible, economically efficient and fair than the central-planning-leaning proposal for large-scale government investment. Higher wages would create more – economically sound – optimism in Germany and thus lead to higher private investment and consumption. I think that the German government and the ECB share the view of the desirability of wage-driven inflation in Germany (“Binnenteuerung” as seen in Switzerland for the past couple of years but with higher figures).

As an aside, higher wages in Germany would probably also increase migration which is part of the Eurozone by design. But as it is not generally accepted by the population, it will be interesting to see how this plays out.

Also, I would like to draw attention to the fact that in this scenario, I assume a continuation of the ZIPR policy of the ECB. It might make sense for many reasons to increase the interest rate prior to a rebalancing through bringing back unit labor costs to pre-Euro levels. But in such a scenario, too many additional variables, cross-dependencies and feedback loops come into play for me to be able to make any kind of sensible prediction, let alone recommendation.

As an afterthought, the following narrative gives a possible reason for why the current imbalances have come into existence at all. After studying the history of the German unification, I have come to the conclusion that the Schröder agenda that led to wage restraint for almost 15 years was dictated largely by internal politics. Trying to prevent internal migration of the East German population, the exchange of “Ostmarks” for German marks was set at too high a rate and wages as well as social security was introduced at a level comparable to the West German one. At the time, there were great worries about the political stability of Germany as a whole if right- or left-wing extremism should take hold in the East. When it became apparent that Western-level costs killed Eastern German industry even more effectively, and that Poland just behind the border had become a much more attractive location for industrial investment, the German government – under the boundary condition that German wages should not grow too far apart – had no other option but limiting labor costs in all of Germany. This worked reasonably well on the Eastern border but caught the rest of the Eurozone completely off-guard, especially Southern Europa that continued in their usual wage-negotiation spirals, and the Northern banks who did not understand or rather were incentivised not to understand that funneling capital to other countries carried a different risk than what they were used to in their home market. All of this is in principle solvable if the governments in the Eurozone do their homework, analyse and learn in the sense that they derive new rules for how the political game has to be played in the Eurozone. For one, this should be that wages should be either completely up to companies, or – if regulated – have to be done after carefully watching labor costs and competitive strengths of all other Eurozone countries. The coordination need not be top-down, it can and should be bottom-up.

Reply